Posts Tagged ‘Mikail Eldin’

The Sky Wept Fire

I write a short column about books for our very local newspaper. I’m sharing one of the columns here so that people learn of Mikail Eldin’s remarkable book.

I’ve written here before about the ISIS Prisons Museum. Now we’ve launched another website dedicated to documenting the prisons of the Assad regime, the Syria Prisons Museum. Both websites have an ‘articles’ section which displays accounts of imprisonment under various other political detention systems around the world, from Iran to Guantanamo Bay. It is interesting to see how the tools of torture and technology of abuse are often very similar even in regimes which are supposedly ideologically very different. Such horrors cross borders more easily than people.

It was in this context that I contacted Mikail Eldin. As a partisan journalist with Chechen independence fighters, he was captured and very brutally interrogated by the Russians before being transferred to an almost equally brutal filtration camp. I asked him to write an account of his imprisonment for the Prisons Museum. He did so – in Russian – and I ‘translated’ it, though I speak no Russian and can’t even read the alphabet, using Google Translate. There were a couple of places in the text where I needed clarification, but basically, the new technology has rendered the job of translator obsolete. Which is somewhat frightening, I think – but that’s another story.

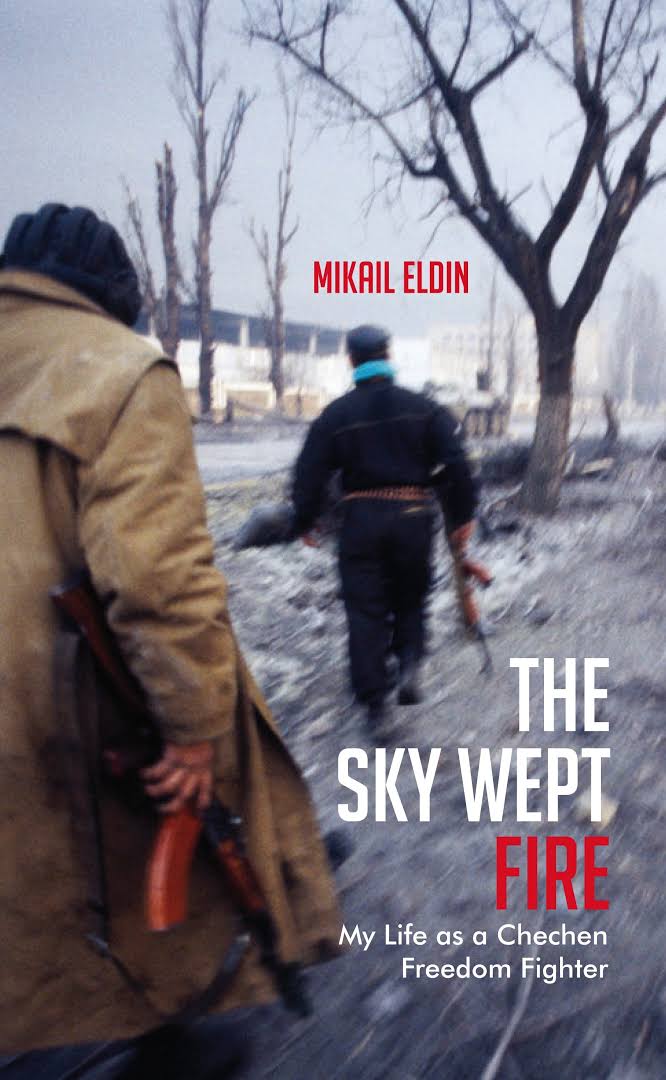

I was so impressed by Mikail’s article that I decided to read his book, “The Sky Wept Fire”, which was translated not by AI but by Anna Gunin, who had put me in touch with him. Mikail was detained during the first Chechen independence war (1994-1996), but he witnessed the second war too (1999-2009). War is, of course, much better experienced vicariously. “It is only possible to write beautifully about war if you have never witnessed it from within,” Mikail writes. I think I disagree, because he has managed to do it. I do agree, however, when he writes, “This is not a seductive story of war for the adventurous or the romantic.” It’s a determinedly unromantic, unsentimental account of terrible events and behavior, but also of the contrary trend, of self-sacrifice and brotherhood.

The writing often slips into second person, that is, Mikail often addresses himself as ‘you’, like this: “You sever yourself from the past and reject the future…” Not much writing does this, and I always like the effect when it does. (Mohsin Hamid’s novel “How to Get Filthy Rich in Rising Asia” does it really effectively, because it’s in part a satire of the self-help genre.) I asked Mikail why he’d chosen the second person, and he responded, “It was very difficult psychologically to describe these events. So I unconsciously began writing this way, distancing myself from them. But in the end, it turned out well.”

The book describes Chechen political and cultural background, and landscapes and cityscapes, and the details of battle, and physical pain and relief. But its treatment of the psychological aspect is the most engaging. This is a raw but also subtle account of the ravages of imperialism, and also of the stark beauties of mountainous Chechnya, a place to visit in an alternate dimension, if it were only free.