Discussing the Missing in Damascus

It was a great honour to speak in the presence of the mothers and fathers of some of the hundreds of thousands of forcibly disappeared people in Syria. We were at the National Museum in Damascus, and I was presenting the Syria Prisons Museum’s research into Branch 215 of Assad’s Military Intelligence. Agnes Callamard, the head of Amnesty International, was speaking too, as was Zeina Shahla of the National Commission for the Missing; Wassil Hamada, who has worked on Sednaya and other prisons; and Reham Hassan, who lost two brothers to ISIS.

Al-Jumhuriya did this report on the event:

I urge everyone to visit the Branch 215 investigation on the website, where there is a virtual 3D tour of the two buildings in Kafr Souseh where the branch was located. Thousands of people were murdered at these locations. The Caesar photographs were taken here. The website also has riveting witness testimony. And everyone should read the investigation by Amer Matar called Branch 215: the Bureaucracy of Murder. It provides a detailed illustration of what Hannah Arendt called the banality of evil.

The Power Shifts Changing the Middle East

I was pleased to be invited again to speak with Faisal al-Yafai on The Lede podcast, connected to the excellent New Lines Magazine. We spoke about Ahmad al-Sharaa’s visits to both Moscow and Washington DC, the role of ideology in today’s Middle East, and even Scottish independence! Raya Jalabi of the Financial Times tals first about the Iraqi militias and the regional changes since & October 2023.

Ahmad al-Sharaa in the White House

This article was first published at Time magazine.

On November 10, President Donald Trump met Syria’s transitional president Ahmad al-Sharaa at the White House. The meeting was remarkable in many ways. It was the first time that a Syrian president had ever been hosted in the White House. Trump and al-Sharaa had briefly met before, in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, on May 14. That date was almost as remarkable as the meeting itself, because it was the twentieth anniversary to the day of Ahmad al-Sharaa’s arrest by American troops for membership of al-Qaeda in Iraq. When al-Sharaa later started fighting in Syria, the US not only declared him a terrorist, it put a $10 million bounty on his head.

The White House welcome looks like a new dawn for Syrian-American relations, given that the US has sanctioned Syria as a ‘state sponsor of terrorism’ since 1979 – and that further sanctions were added by the Reagan, George W. Bush and Obama administrations.

And it’s certainly quite a turnaround for a former jihadist – though perhaps not as much as it first seems. Al-Sharaa was in prison for most of the Iraqi civil war, so he didn’t participate in attacks on Shia civilians. Released just as the Syrian Revolution was beginning in March 2011, he returned to Syria to establish a militia called Jabhat al-Nusra, which later transformed into Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS). These organizations focused on fighting Assad and the Iranian militias that supported him. They never attacked the West, and they steered clear of the mass civilian casualty operations favoured by Iraqi jihadists.

Al-Sharaa broke definitively with ISIS in 2013, and has fought it continuously since 2014. In power, he aims for good relations with the world rather than apocalyptic war. And where ISIS fielded a morality police to impose a dress code, in al-Sharaa’s Damascus, women wear what they like.

The US had conducted multiple anti-ISIS operations in HTS-ruled Idlib, including the one that killed ISIS ‘caliph’ Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in 2019. Though there was no direct coordination, HTS fighters did not attack the US special forces. Indirect understandings intensified into direct cooperation when al-Sharaa assumed power on December 8 last year, leading to at least eight joint operations. Now, after the meeting in the White House, Syria has announced its formal integration into the Global Coalition against ISIS. This will lead to still more joint action. Even more significantly, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) – the Kurdish-led militia that controls large parts of northeastern Syria – can no longer claim to be the Coalition’s boots on the ground. This is a step towards Syria’s reunification under central authority.

Read the rest of this entry »Documenting the Means of Murder

The Syria Prisons Museum has now launched with an event in the National Museum in Damascus, and as a website here. The first in-depth investigation, complete with 3D virtual tour, witness testimonies, and more, is on Sednaya Prison.

I wrote the following article for Time magazine about the purpose and methodology of the Syria Prisons Museum, and some of its findings.

In Sednaya Prison, the names of those sentenced to death were called once a week. These men were removed from the group cells and chained together. They were usually held in designated cells for their last three days of life, during which time they were deprived of food and water. Apparently this made them die more easily, less messily. The killing itself was done on the ground floor, in the reception hall, using a gallows constructed of metal pipes which was large enough to dispatch several victims at once.

The victims were not criminals but political prisoners arrested for protesting, organizing or fighting against Syria’s Bashar al-Assad regime, which finally collapsed last December after 14 years of revolution and counter-revolutionary war. Sednaya Prison – otherwise known as ‘the human slaughterhouse’ – was the most notorious of the dozens of prisons run by the regime. Prisons had always been central to Assadist rule. From 1970 – when Bashar al-Assad’s father Hafez seized power in a military coup – a comprehensive system of surveillance, detention and torture terrified Syrians and turned the country into a “kingdom of silence”.

Syrians found their voices in 2011 when, in the context of the regional ‘Arab Spring’, they rose up against the regime. But they paid an enormous price. Assad responded by declaring war on the people. Iran and Russia sent troops and war planes to help him, while Turkey and Gulf states backed rebel militias. And as the cities burned, the prisons were transformed into death camps. The Syrian Network for Human Rights reported in August that at least 160,000 men and women remain unaccounted for after being forcibly disappeared by the Assad regime. Many of their corpses fill the mass graves which are still being uncovered today.

The result is the mass traumatisation of Syrian society. Recovery from such terrible crimes requires transparency, understanding, and at least a degree of justice. And the first step towards these aims is to clearly establish the facts of what happened. A Syrian-led organisation called the Prisons Museum is at the forefront of this effort. It brings together investigative journalism, human rights advocacy and cutting-edge technology to shed light on horrors which the perpetrators would prefer remain hidden. (I am the Museum’s English-language editor.)

The surviving prisoners in Sednaya Prison were liberated by rebel fighters and local civilians in the early hours of December 8 last year, as Bashar al-Assad fled to Moscow. A few days later, a Prisons Museum team entered the facility and began to document every room and object.

Read the rest of this entry »The ISIS Legacy in Syria

This was a great discussion the Prisons Museum conducted with Shiraz Maher, author of Salafi-Jihadism: the History of an Idea. On behalf of the Prisons Museum there’s me and Dagmar Hovestadt, our communications manager. Here we discuss whether ISIS has a future, and what the transitional government tells us about jihadism, or post-jihadism, in the 21st Century.

Constructive Criticism

Here I am on the Eon podcast with some post-Suwayda constructive criticism for the Syrian transitional authorities.

The Hisba Diwan

At the ISIS Prisons Museum you can now read our investigations into the Hisba Diwan, a supposed behaviour police force which the organization imposed on society in eastern Syria and western Iraq. You can also go on virtual 3D tours of Hisba Diwan prisons, watch victim testimony, and more.

The Museum has broadcast a series of webinars on the investigations. The most recent involves my colleagues and I talking with Syrian journalist Hussam Hammoud about surveillance under the Hisba Diwan and its effects on society. Here it is:

The Syrian Centenary Initiative

On 23 July, something called The Syrian Centenary Initiative appeared on Facebook. This was the first sign I’d seen of organized opposition other than by militia. The Initiative’s declaration explained that it had been formed in response to the massacres in Suwayda and the urgent threats to Syrian unity posed by internal violence and external actors like Israel. It pointed out the essential fact that the “logic of mobilization” – that is, the current government’s repeated mobilization of one sector of society against another – contradicts the “mentality of state [building].” It called on the “temporary authority” to engage in “shared national emergency efforts” to solve the crisis.

The Initiative had ten demands. Here they are, in brief summary (and this is based on my translation from the Arabic scribbled during a train ride. If you think I’ve got the emphasis of anything wrong, or missed out anything essential, please let me know):

1. A complete ceasefire in Suwayda.

2. Guarantees that the violence will not be repeated.

3. An immediate stop to population transfers and demographic change.

4. For all sides in Syria to accept the principle that no weapons should be held by any party other than the state.

5. The formation of an independent investigative committee into the Suwayda violence consisting of Syrian, Arab and international legal and human rights experts.

6. Rapid modifications to the Constitutional Declaration, including a law to allow the formation of political parties and civil society organizations, and changes to the way the parliament is formed.

Read the rest of this entry »Syria after Sweida on the Lede

I and then Zaina Erhaim talk about Syria with Faysal Yafai for The Lede, the podcast run by New Lines magazine. Follow this link to listen.

The Wounds of the Past, and Transitional Justice

This essay was first published at New Lines Magazine.

In dry hills half an hour’s drive outside Damascus, Sednaya Prison comes into view. A squat three stories covering a good deal of land, it imposes on the vision as we approach from below. Repeated rings of barbed wire and mine fields surround the main building. The Assad regime’s organized graffiti praising the leader and describing the (non-existent) struggle against Israeli occupation still covers the outer buildings which housed the guards and their workshops until the regime collapsed on December 8 2024.

The whirlwind of revolutionary change has hit the place. Rubble and rubbish litter the entrance. I and the photographers climb a few steps into the reception room where prisoners were previously pushed into narrow caged corridors and stripped of their clothes. It isn’t hard to imagine the screams and thuds as new arrivals received their ‘reception party’ beatings. Although on second thoughts, my imagination may be overdoing it. Absolute silence was often enforced on the victims, even during torture.

Amongst the detritus here on the filthy tiled floor, a couple of artificial legs lie marooned. They are made of very basic plastic, one to fit beneath a knee, one to replace an entire limb from the hip down. I can’t understand why they’re still here. Surely their owners didn’t discard them when they fled? Later, however, I read the transcript of an interview with a survivor of the prison. He described the reception room process: “If you have a prosthetic leg, they throw it away. If you have glasses, they get rid of them.”

At the center of the prison is a spiral staircase made of metal and surrounded by metal bars. This connects (or for the prisoners, separated) the three stories and the three wings fanning out from the center. Nine cells recede down each corridor. These are the group cells, in which dozens of men were crammed. Very thin, dark brown blankets cover the floor. There is a bad odour or the memory of one, a discomforting sweet staleness.

Down the stairs are the solitary cells, so-called because they aren’t big enough to fit more than one man, though in fact three, four or five men were often forced inside. Each cell contains a dirty squat toilet, from which the men also had to drink. Food was delivered through a slot at the bottom of the heavy metal door. There is no light inside. The prisoners existed in absolute darkness. Sightlessness as well as soundlessness contributed to the deprivation. There is writing on some of the walls nevertheless, apparently etched by fingernails. A name of a man and his city, Tartous. A date in 2014. A count of days, though in the dark the days could only have been guessed at.

The smell is stronger here. One of the photographers explains that in the first days after the liberation streams of human waste flowed from the cells into the hallway. We’re stepping now on blankets put down to absorb the filth. They have hardened in the dry air in the months since, but the smell persists. This is despite the thick clouds of incense currently being burnt upstairs, where the group cells are. That sweetness covers but doesn’t hide the deeper, more disturbing sweetness of persistent degradation.

If this works as a symbol – and we are in need of symbols, of any tools we come across to help us comprehend – it serves to embody the need for a deep cleaning of Syrian society. Superficial treatment won’t do, for the crimes committed in the Assad prisons system can be rightly described as radically evil. Of the at least 130,000 people missing in Assad’s dungeons, only about 30,000 were released in the hours following the fall of the regime. That means at least 100,000 victims were murdered in Sednaya and other prisons, by torture or starvation or medical neglect. Their corpses pack the mass graves found at Qutayfa and many other sites. The victims were not criminals, but people who had spoken, protested, organized, or in some cases fought against the regime.

Read the rest of this entry »Unhomely Homes: Hassan Blasim’s Sololand

This review was first published at the New Arab.

The narrator of one of the stories in Hassan Blasim’s “Sololand” dreams that he’s written a story in colloquial Iraqi Arabic rather than in standard fusha. He begins reading it to a “hall full of writers, critics and poets … all smoking and glaring at each other.” As soon as he finishes the first line, which repeats a vulgar but realistic Iraqi proverb, “the first shoe hit me from the front row, and then more shoes came thick and fast like a swarm of locusts.”

This reminds me of my own experience attending a literary festival in Erbil, Iraqi Kurdistan, back in 2011. I didn’t commit the sin of reading out a story written in aamiya, but I did make the comparable faux pas of praising Hassan Blasim’s writing to a hall full of Iraqi literary figures. I repeated what I’d written in the Guardian, that Blasim was perhaps the best writer of Arabic fiction alive. This didn’t provoke actual shoes, but it did result in fuming outrage and several angry ripostes. Blasim uses bad language, they said. He is vulgar. He concentrates on topics that are unsuitable for literature.

O but that’s what used to be said about James Joyce, another iconoclast at work in a period of social and cultural turmoil. Those working to find new ways of expressing new realities will inevitably offend sensibilities and step on people’s toes, especially in a country with as many taboos as Iraq.

Iraq is the country that Blasim escaped. His own toes were trodden on in the process. Some of his fingers, to be precise, were cut off during the journey, which took him over the mountains into Iran, then through Turkey and various European countries, working unregistered jobs in dangerous conditions to pay his way. Echoes of the journey can be heard in “The Truck to Berlin”, a horror story from his first collection, “The Madman of Freedom Square” (2009).

That was the collection which elicited my praise, and which I often still give as a present. If the question is: How to write about war, when war provides truths every day that are so much stranger and more macabre than fiction? Then this book answers the question with an inimitable blend of surrealism, cynicism and black humour. (Ahmad al-Saadawi’s very up-to-date fable “Frankenstein in Baghdad” offers another very different answer, and the late Syrian novelist Khaled Khalifa, in “Death is Hard Work”, by far his most pared-down novel, offers yet another.)

“Sololand”, Blasim’s latest collection, is a further high achievement. Two of the three stories offer visions of the kind of social breakdown that forces Iraqis to flee their country, and sandwiched between them another story offers a similarly dark picture of the situations in which they arrive in their supposed lands of refuge.

Read the rest of this entry »The End of the Fairy Tale

An edited version of this piece was published at UnHerd. I disagree with the headline there – Syria Can’t Escape War – though at present it looks like the cycle of violence will keep on rolling. Along with the Assadist violence and the sectarian killings by men linked to the new authorities, there have been deals with the SDF and representatives of the Druze. It’s true that these are only preliminary steps – that the SDF deal was spurred by the American desire to withdraw, for instance, that the PKK may seek to quash part of the deal (SDF integrating into national army) and Damascus may seek to renege on another (decentralization). But if Syrians keep working intelligently, the country can indeed escape war, and build something better. Anyway, here’s the piece:

The sudden collapse of the Assad regime on December 8 2014, without any civilian casualties, felt like a fairy tale. Syrians had feared that the Assadists would make a last stand in Lattakia, the heartland of the regime and of the Alawite sect from which its top officers emerged. Many also feared there would be a sectarian bloodletting as traumatised members of the Sunni majority took generalised revenge on the communities which had produced their torturers. None of that happened then. But some of it has now. On March 6, an Assadist insurgency killed hundreds in Lattakia and other coastal cities. Then men associated with the new authorities, as well as suppressing the insurgency, committed sectarian atrocities, summarily executing their armed opponents, and killing well over a hundred Alawite civilians.

This is the first sectarian massacre of the new Syrian era, and it casts a fearsome shadow over the future. The revolution was supposed to overcome the targeting of entire communities for political reasons. Now many fear the cycle will continue.

The previous regime was a sectarianizing regime par excellence, both under Hafez al-Assad, who ruled from 1970, and under Hafez’s son Bashar, who inherited the throne in 2000. This doesn’t mean that the Assads attempted to impose a particular set of religious beliefs, but that they divided in order to rule, exacerbating and weaponizing fears and resentments between sects (as well as between ethnicities, regions, families, tribes). They carefully instrumentalised social differences for the purposes of power, making them politically salient.

The Assads made the Alawite community into which they were born complicit in their rule, or at least, to appear to be so. Independent Alawite religious leaders were killed, exiled or imprisoned, and replaced with loyalists. Membership in the Baath Party and a career in the army were promoted as key markers of Alawite identity. The top ranks of the military and security services were almost all Alawite.

In 1982, during their war against the Muslim Brotherhood, Assadists killed tens of thousands of Sunni civilians in Hama. That violence pacified the country until the Syrian Revolution erupted in 2011. The counter-revolutionary war which followed can justifiably be thought of as a genocide of Sunni Muslims. From the start, collective punishment was imposed on Sunni communities where protests broke out, in a way that didn’t happen when there were protests in Alawi, Christian or mixed areas. The punishment involved burning property, arresting people randomly and en masse, then torturing and raping those arrested. As the militarization continued, the same Sunni areas were barrel-bombed, attacked with chemical weapons, and subjected to starvation sieges. Throughout the war years, the overwhelming majority of the hundreds of thousands of dead, and of the millions expelled from their homes, were Sunnis.

Alawi officers and warlords were backed in this genocidal endeavour by Shia militants from Lebanon, Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan, all of them organized, funded and armed by Iran. These militias – with their sectarian flags and battle cries – were very open about their hatred of Sunnis.

The worst of sectarian provocations were the massacres perpetrated in towns in central Syria, especially in 2012 and 2013, places like Houla, Tremseh, and Qubair. The modus operandi was that the regime’s army would first shell a town to make opposition militias withdraw, then Alawi thugs from nearby towns would move in to cut the throats of women and children. It’s important to note that these were not spontaneous assaults between neighbouring communities, but were carefully organized for strategic reasons. They were intended to induce a backlash which would frighten Alawites and other minorities into loyalty. This fitted with the regime’s primary counter-revolutionary strategy. Early on it had released Salafi Jihadis from prison while rounding up enormous numbers of non-violent, non-sectarian activists. For the same reason, it rarely fought ISIS – which in turn usually focused on taking territory from the revolution.

Read the rest of this entry »The Tragic Arc of Baathism

An edited version of this essay was published by Unherd.

As well as the most persistent, the Syrian Revolution has been the most total of revolutions. Starting in early 2011 and culminating unexpectedly in December of 2024, it – or rather, the Syrian people – managed to oust not only Bashar al-Assad, but also his army, police and security services, his prisons and surveillance system, and his allied warlords, as well as the imperialist states which had kept him in place. The revolutionary victory marked the end of a dictatorship which had lasted 54 years (under Bashar and his father, Hafez), and also the final, belated death of the 77-year-old Baath Party, once the largest institution in both Syria and Iraq.

Founded in Damascus in April 1947, the Arab Socialist Baath Party went through three major stages, each closely related to the vexed political history of the Arab region. The first stage was one of abstract and unrealistic ideals. Baathism was the most enthusiastic iteration of Arab nationalism. Whereas Egyptian president Gamal Abdul Nasser understood the Arab world as a strategic depth for Egypt and a field in which he could exert his own influence, the Baathists had an almost mystical apprehension of the Arabs as a nation transcending historical forces, one which had a “natural right to live in a single state.”

The founding figures were Syrians who had immersed themselves in European philosophy (Bergson, Nietzsche and Marx) while studying at the Sorbonne in Paris. Two of the three founders were members of minority communities, and it’s useful to think of Baathism as a means of constructing an alternative identity to Islam. While Salah al-Din Bitar was a Sunni Muslim, Michel Aflaq was an Orthodox Christian and Zaki Arsuzi was an Alawi who later adopted atheism. The three mixed enlightenment modernism with romantic nationalism. Arsuzi, for instance, believed Arabic, unlike other languages, to be “intuitive” and “natural”. And Aflaq turned the usual understanding of history on its head. He considered Islam to be a manifestation of “Arab genius”, and deemed the ancient pre-Islamic civilizations of the fertile crescent – the Assyrians, Phoenicians, and so on – to be Arab too, though they hadn’t spoken Arabic.

Like other grand political narratives of the 20th Century, Baathism was an attempt to repurpose religious energies for secular ends. The word Baath means “resurrection”. The party slogan was umma arabiya wahida zat risala khalida, or “One Arab Nation Bearing an Eternal Message”, which sounds strangely grandiose even before the realization that umma is the word formerly used to describe the global Islamic community, and that risala is used to refer to the message delivered by the Prophet Muhammad.

The party’s motto – “Unity, Freedom, Socialism” – referred to the desire for a single, unified Arab state from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Gulf in the east, and from Syria in the north to Sudan in the south. The Arab state should be free of foreign control, and should construct a socialist economic system.

This dream was spread by countryside doctors and itinerant intellectuals. In those early days, the leadership consisted disproportionately of schoolteachers and the membership of schoolboys. In 1953, however, the party merged with Akram Hawrani’s peasant-based Arab Socialist Party. This brought it a mass membership for the first time, and it came second in Syria’s 1954 election.

By then, episodes of democracy were becoming more and more rare. Since Colonel Husni al-Zaim’s March 1949 coup – the first in Syria and anywhere in the Arab world – politics was increasingly being determined by men in uniform. The most significant of these soldiers was Nasser, who seized power in Cairo in 1952, then became a pan-Arab hero when he confronted the UK, France and Israel over the Suez canal in 1956.

Read the rest of this entry »Citizenship or Sectarian Splintering

A slightly different version of this was published at the New Arab.

The fascist threat is by no means over in Syria, and neither is the revolution.

The showdown between irreconcilable Assadists and the country’s new rulers which didn’t erupt on December 8 last year is happening now. Worse, the attendant sectarian breakdown which Syrians feared may be underway.

On the sixth of March, Assadists in the coastal areas launched coordinated attacks on Syrian security forces, killing over 400. Snipers also attacked and killed civilians, killing hundreds. Hospitals and ambulances were targeted, and highways were closed by gunfire.

The violence was met by a massive popular response. In cities across Syria demonstrations came out in support of the government and to demand the rapid suppression of the Assadists. People rejected absolutely the idea of returning to the terrible past of torture chambers and barrel bombs. They also expressed fury at the Assad regime’s “remnants”, as they are known, for refusing the reconciliation offered. Despite their extremist background, the new authorities had surprised many Syrians by their pragmatic, intelligent approach to the old regime, offering an amnesty to all fighters except the top level war criminals, and assuring people of all sects and ethnicities that their rights would be assured. Syrians hoped that Assadists, and the Alawite community from which many emerged, would, in turn, accept the wrong they had done the country, and seek to make amends. Instead they were attacking hospitals.

Tens of thousands of angry men rushed to the coast to support the government. As well as convoys of pro-government militia, armed civilians joined the flood, despite an interior ministry statement asking citizens not to engage.

Though fighting still continues, government forces rapidly regained control over urban centres. But abuses against Alawite civilians risk turning this immediate victory into a longer-term defeat.

There were numerous field executions of Assadist fighters. Far worse, the reliable Syrian Network for Human Rights says at least 125 civilians were summarily executed in various locations. This – the first massacre perpetrated by men associated with the new authorities – is a disaster.

Read the rest of this entry »A Background of Blood

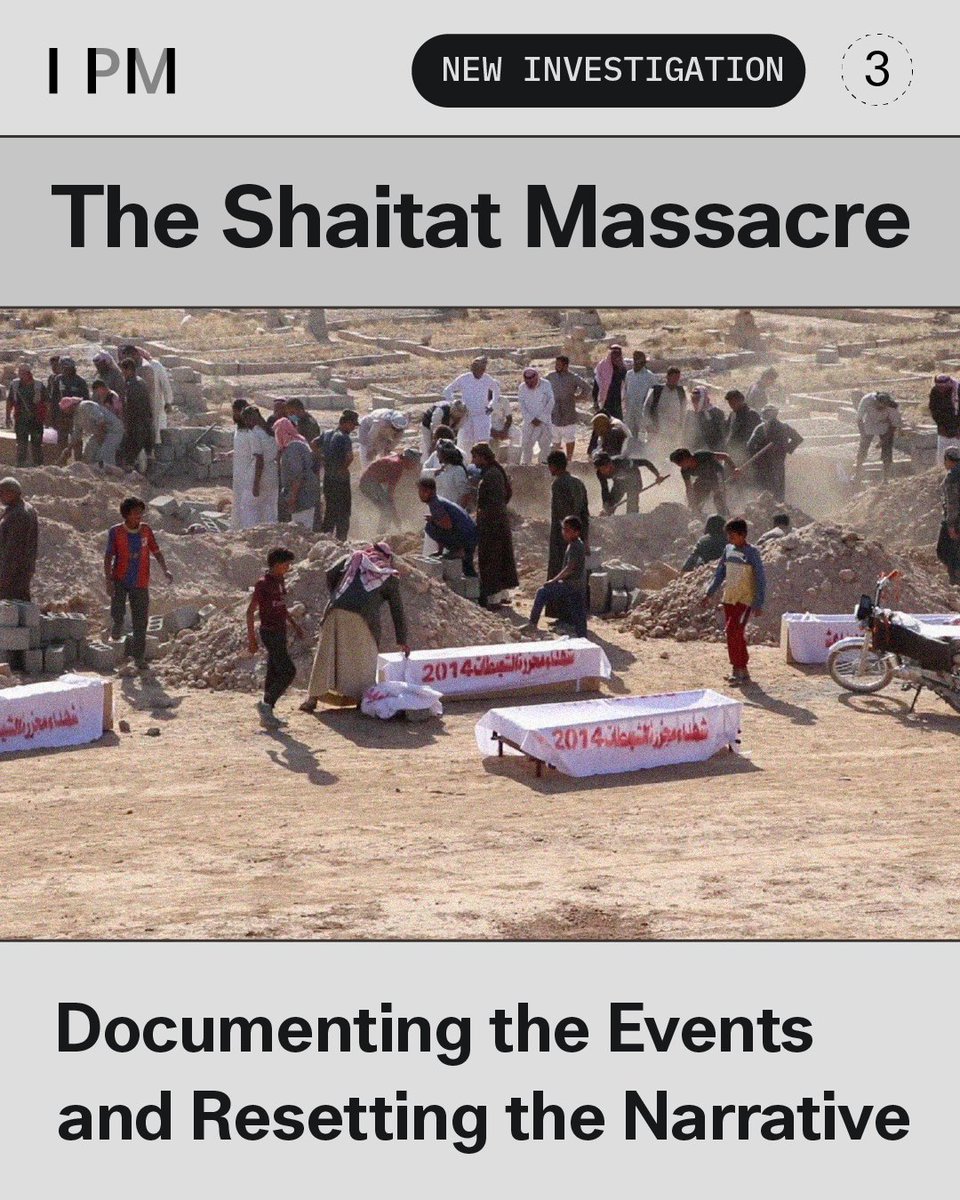

The ISIS Prisons Museum has produced the most comprehensive study yet of the 2014 Shaitat Massacre, the worst ISIS atrocity in Syria. The focus on the massacre includes witness testimonies, 3D prison tours, investigations into some of the dozens of prisons established in the Shaitat areas, and a detailed report on the killing and mass displacement of the clan and the looting and destruction of its property. The report is by far the most serious treatment yet of the events. It’s written by Sasha and Ayman al-Alo, and can be read here.

ISIS violence didn’t drop from the skies. It emerged from a context of massacres in Syria and Iraq perpetrated by the Assad regime, the Saddam Hussein regime, and various actors in the Iraqi and Syrian civil wars, including US troops and sectarian Shia militias. I have written a text to give this context. It’s called A Background of Blood, and can be read here.