Archive for January 2017

Dancing in Damascus

by Wissam al-Jazairy

This review of miriam cooke’s new book was published at the Guardian.

Syria’s revolution triggered a volcano of long-repressed thought and emotion in cultural as well as political form. Independent newspapers and radio stations blossomed alongside popular poetry and street graffiti. This is a story largely untold in the West. Who knew, for instance, of the full houses, despite continuous bombardment, during Aleppo’s December 2013 theatre festival?

“Dancing in Damascus” by Arabist and critic miriam cooke (so she writes her name, uncapitalised) aims to fill the gap, surveying responses in various genres to revolution, repression, war and exile.

Dancing is construed both as metaphor for collective solidarity and debate – as Emma Goldman said, “If I can’t dance, it isn’t my revolution” – and as literal practice. At protests, Levantine dabke was elevated from ‘folklore’ to radical street-level defiance, just as popular songs were transformed into revolutionary anthems.

Cooke’s previous book “Dissident Syria” examined the regime’s pre-2011 attempts to defuse oppositional art while giving the impression of tolerance. The regime would fund films for international screening, for instance, but ban their domestic release.

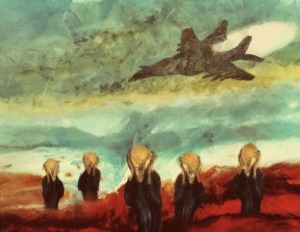

by Souad al-Jundi

“Dancing in Damascus” describes how culture slipped the bounds of co-optation. Increasingly explicit prison novels and memoirs anticipated the uprising. Once the protests erupted, ‘artist-activists’ engaged in a “politics of insult” and irony. Shredding taboos, the Masasit Matte collective’s ‘Top Goon’ puppet shows, Ibrahim Qashoush’s songs and Ali Farzat’s cartoons targeted Bashaar al-Assad specifically. “The ability to laugh at the tyrant and his henchmen,” writes cooke, “helps to repair the brokenness of a fearful people.”

As the repression escalated, Syrians posted atrocity images in the hope they would mobilise solidarity abroad. This failed, but artistic responses to the violence helped transform trauma into “a collective, affective memory responsible to the future”.

2084: The Recurring Liberal Apocalypse

This was first published at the National.

This was first published at the National.

The true subject of science fiction is always the present. Its imagined futures are mirrors to today’s hopes and fears. George Orwell’s “1984” simply shifted the numbers of the year in which he wrote the book – 1948 – and made a metaphor of that time’s dark politics. Likewise “2084”, the latest from Algerian novelist Boualem Sansal, is addressed to, and in some way is part of, very contemporary woes.

Sansal lays out a fantastically detailed dystopia in complex and often elegant prose. After the Great Holy War killed hundreds of millions, an absolutist theocracy has been founded by Abi the Delegate, servant of the god Yolah. Abi’s rule is secured by such institutions as the Apparatus and the Ministry of Moral Health, and displayed by frequent mass slaughters of heretics in stadia built for the purpose. The nine daily prayers are compulsory. Women must cloak themselves in thick ‘burniqabs’.

Dissent, individuality, and progress have been abolished. The future must be a strict replica of the past. All languages are banned save the state-invented ‘Abilang’.

Ati, the story’s vague hero, is sent to a sanatorium in the mountains to cure his tuberculosis. Here he hears rumours of a nearby border, a limit to Abi’s reign. The notion “that the world might be divided, divisible, and humankind might be multiple” sparks a crisis of doubt in him, and then a journey of discovery.

At times “2084” suffers from science fiction’s most common pitfall: an unwieldy listing of technical or political information describing the imagined world outweighs and obscures the necessary human information. Sansal’s characters are somewhat two-dimensional, and the plot can seem almost accidental.

It is best, therefore, not to read this as a conventional novel but as a mix of satire, fable, and polemic.

The ‘Hakawati’ as Artist and Activist

I interviewed my friend Hassan Blasim, a brilliant writer and a wonderful human being, for the National.

I interviewed my friend Hassan Blasim, a brilliant writer and a wonderful human being, for the National.

Hassan Blasim is an Iraqi-born writer and film-maker, now a Finnish citizen. He is the author of the acclaimed story collections “The Madman of Freedom Square” and “The Iraqi Christ” (the latter won the Independent Foreign Fiction prize), and editor and contributor to the science fiction collection “Iraq +100”. His play “The Digital Hat Game” was recently performed in Tampere, Finland.

Because it’s so groundbreaking, his work is hard to categorise. It deals with the traumas of repression, war and migration, weaving perspectives and genres with intelligence and a brutal wit.

Why do you write?

To be frank, I would have killed myself without writing.

If you read novels and intellectual works since your childhood, your head is filled with the big questions. Why am I here? What’s the meaning of life? You apply this questioning to the mess of the world around you – why is America bombing Iraq? why are we suffering civil wars? – and you realise the enormous contradiction between your lived reality and the ideal world of knowledge. On the one hand, peace, freedom, and our common human destiny, and on the other, borders, capitalism and wars.

Writing for me began as a hobby, or a way of dreaming. And then when I witnessed the disasters that befell Iraq, it became a personal salvation. It wouldn’t be possible to accept this world without writing.

Maybe writing is a psychological treatment, or an escapism. It’s certainly a dream. But it’s also to confront the world, and to challenge all the books that have been written before. And it’s a process of discovery. It’s all of these things.

Our Fates Are Linked

a poster from occupied Syria

Dezeray Lyn interviewed me for the Arab Daily News on the next stage in Syria, propaganda and conspiracy theories, and the connections between Syria and the world. The full article is here.

DL: I think it cheats every revolutionary, pro democracy organizer and all lovers of the land to only discuss Syria only in post counter-revolutionary, post civil war contexts. Can you intimate us with life in Syria and Aleppo before the Arab Spring uprising in terms of organizing/living/arts/love/culture under an oppressive Assad dictatorship?

RYK: Syria was in many ways a lovely country. Foreigners who visited generally loved it, and Syrians were very proud of it. Syria has a fine climate, one of the world’s great cuisines, unparalleled historical riches, and a diverse and friendly population.

It was also, beneath the surface, a tragic country, one which had suffered enforced poverty and dislocation under first Ottoman and then French imperialism, then bitter class oppression, and then sixty years of dictatorship in which a new ruling class of security officers and loyal businessmen coalesced. All forms of government exploited sectarian, ethnic, regional and tribal differences amongst the people, the better to control them. The Baathist dictatorship in particular ruled by violence and fear. About 30,000 people were killed in Hama in 1982, and thousands of dissidents disappeared in the regime’s torture prisons. Civil society was crushed.

Despite the extreme repression, Syrians produced some remarkable poetry, music, drama and films. And dissident thought continued to surface, particularly in the brief and abruptly aborted ‘Damascus Spring’ in 2000, after Bashaar al-Assad inherited the dictatorship from his father Hafez.

Bashaar shut down the political and social opening. Instead, he ‘opened’ the economy. In effect this meant a set of neo-liberal and crony capitalist reforms which enormously enriched his own family and friends while impoverishing large swathes of the population. This was the context for the 2011 uprising.