Archive for the ‘writing’ Category

Nursery Rhyme

| Nursery Rhyme[1] |

| How arrogant is the Englishman of whatever creed or hue who avers the Arab native is inferior to the Jew[2] |

| How Blinkened the American And all that he can see is a Disneyfied Holy Land through Judeao-Christian lunacy[3] |

| How ugly is the German with his foolish liberal pride He’s got a new set of stories but still commits genocide |

| How insane is the Israeli now that history’s put him here He builds his walls and mows his lawns in brute anger and red fear |

| How deceitful the Iranian and what a hypocrite Instead of liberating Palestine he forces Syria to submit |

| How corrupt the craven Arabs the dictators bound for hell[4] The blood of us is on their hands Our souls is what they sell |

[2] See Winston Churchill et al.

[3] Or ‘through Judeao-Christian lunettes’

[4] The author is too humble an agnostic to claim to know the actually destined destination of the dictators. ‘Hell’ here, then, as may or may not be the case there, in the afterlife, acts as a metaphor rather than a literal fact

Capital

Here is an extract from the novel I was writing before I got two jobs. The novel might be called ‘Whale’. I’ve written the first of five parts, and one day when things calm down I may be able to write the rest. The extract was published in the Critical Muslim’s Capital issue.

The ‘Hakawati’ as Artist and Activist

I interviewed my friend Hassan Blasim, a brilliant writer and a wonderful human being, for the National.

I interviewed my friend Hassan Blasim, a brilliant writer and a wonderful human being, for the National.

Hassan Blasim is an Iraqi-born writer and film-maker, now a Finnish citizen. He is the author of the acclaimed story collections “The Madman of Freedom Square” and “The Iraqi Christ” (the latter won the Independent Foreign Fiction prize), and editor and contributor to the science fiction collection “Iraq +100”. His play “The Digital Hat Game” was recently performed in Tampere, Finland.

Because it’s so groundbreaking, his work is hard to categorise. It deals with the traumas of repression, war and migration, weaving perspectives and genres with intelligence and a brutal wit.

Why do you write?

To be frank, I would have killed myself without writing.

If you read novels and intellectual works since your childhood, your head is filled with the big questions. Why am I here? What’s the meaning of life? You apply this questioning to the mess of the world around you – why is America bombing Iraq? why are we suffering civil wars? – and you realise the enormous contradiction between your lived reality and the ideal world of knowledge. On the one hand, peace, freedom, and our common human destiny, and on the other, borders, capitalism and wars.

Writing for me began as a hobby, or a way of dreaming. And then when I witnessed the disasters that befell Iraq, it became a personal salvation. It wouldn’t be possible to accept this world without writing.

Maybe writing is a psychological treatment, or an escapism. It’s certainly a dream. But it’s also to confront the world, and to challenge all the books that have been written before. And it’s a process of discovery. It’s all of these things.

Brothers Blood

I’m honoured that the wonderful poet Golan Haji has translated the prologue to my novel-in-progress for al-Arabi al-Jadeed. Here it is:

I’m honoured that the wonderful poet Golan Haji has translated the prologue to my novel-in-progress for al-Arabi al-Jadeed. Here it is:

3 فبراير 2015

First There Was the Word

I and lots of other writers participated in this BBC radio 4 programme on ‘British Muslim writing’. The programme is written and presented by Yasmin Hai. Those interested in this may also be interested in Clare Chambers’s book “British Muslim Fictions“.

Tooth

The Glasgow Film Theatre asked me and nine other writers based in Scotland to respond to the theme ‘For All.’ My response is part of the novel I’m writing at the moment. The extract inspired this very brief but strangely wonderful animation by David Galletly:

You can read Tooth here at the GFT’s website..

Translation and Conflict

Here was me, Dan Gorman and Samia Mehrez talking about translation and conflict for the Literary Translation Centre at the London Book Fair 2013.

Lion One and Lion Two

Lion One

misnamed hollow lion

wearing his megalo mane

a pointy-head frown

toothsome

grin

says the important thing

is to believe in a cause

it allows him to kill

the causeless the useless

the malformed will

rule

Becoming Sane

imagine the poor man

his eyes dimming his ears clouding

colour draining from the sky

movement stiffening in the trees

descending

from prickly elevation to prosaic daily sludge

in the grey city in the grey century

Maltese Interviews

I was invited to the Malta Mediterranean Literature Festival. Malta is a fascinating place, with a fascinating Arabic-origin language, and I met many fascinating writers there. I’ll write about it soon. In the meantime, here are a couple of interviews with me from the Maltese press.

First, from the Times of Malta.

Albert Gatt discusses hedgehogs, dictators and parricide with author Robin Yassin Kassab.

As the crackdown in Syria continues, and the revolution in Libya inches towards resolution, another blow is dealt to the grand narrative of the Arab nation which various dictators – self-styled fathers to their people – used to justify their rule. Can literature offer a nuanced view that counters this narrative’s deadly simplicity?

This year, the Malta Mediterranean Literature Festival, organised by Iniżjamed and Literature Across Frontiers, will focus on the Arab Spring.

One of the guest writers is Robin Yassin Kassab, who appears courtesy of the British Council (Malta). Born in West London of Syrian descent, Yassin Kassab is a regular contributor to the press and blogs on http://qunfuz.com – qunfuz is Arabic for hedgehog or porcupine.

In his first novel, The Road from Damascus (Penguin, 2009), Sami, the son of Syrian migrants in London, struggles to carry the mantle bequeathed to him by his father, a staunchly secular Arab intellectual.

But the turmoil of his own private life and the havoc wreaked by 9/11 force him to challenge the worldview he has inherited, in whose name his father committed the ultimate betrayal.

I’m intrigued by the name of your blog – Qunfuz. In what sense is the writer a hedgehog?

al-Qa’ida Speaks

our dead live more deeply

water flows stalactite

our lungs do not breathe

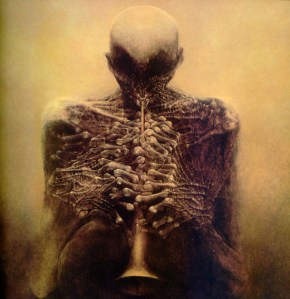

Iraqi Fragments

Between the rivers where words begin

Strange architecture of flesh drawn by war

Babies born in the form

of bunches of grapes

And men who die tongueless

women die breastless

Not human any more.

The Syrian People

walls to scrawl graffitti on

slabs of stone for carving

if you crush it it sings a song

changes colour with a stamping

meat to hang upon a hook

wire conducting electricity

balls to kick around the yard

to reduce to pure simplicity

wet cloth to dessicate

sweet sounds to silence

flaps and buttons to be tugged off

obscenities to be licensed

unruly features to be trimmed and then

punished, then punished, then punished –

the guilty corpse, the damned – to be

punished, dissected, turned inside out

so all the world can see

Hama Hallucinated

Here’s an extract from my novel The Road From Damascus, in which the dying Ba’athist Mustafa Traifi hallucinates the Hama massacre of 1982. Back then the regime really was fighting an armed group – the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood. I don’t much like my writing of four years ago, but the passage is rustling in my mind today for obvious reasons.

What’s time to a corpse? From the moment of its death, time becomes a foreign territory, a land stranger and more distant with every minute, every decade, until soon there’s nobody left to put a face to the corpse’s name, to the name of the dust, and soon the letters of its name have sunk into the graveslab’s grain, and the stone itself is broken or buried or dug up. And the land which was once a graveyard is overgrown, or shifted, or levelled. And the planet itself dead, by fire or ice, and nobody at all anywhere to know. No consciousness. As if nothing had ever been.

Unless there is Grace watching and waiting for our helplessness.

There is no permanence for a corpse, not even for corpse dust. Or corpse mud, in this country. All this graveyard sentiment. You may as well shoot it into outer space. Into the stars.

Mustafa Traifi is dreaming intermittent dreams of war. He sees the city of Hama from above and within. Sees the black basalt and white marble stripes. The mosque and the cathedral. The thin red earth. The tell of human remains, bones upon bones. The Orontes River rushing red with the blood of Tammuz, the blood of Dumuzi, the dying and rising shepherd god. The maidens weeping on the river banks.

Life is precarious. This place is thirty kilometers from the desert. The river raised by waterwheels feeds a capillary network of irrigation and sewage channels, and agricultural land in the city’s heart. Traffic is organised by the nuclei of marketplaces (Mustafa sees from above, like the planes) where there are householders and merchants and peasant women in red-embroidered dresses and tall men of the hinterland wearing cloaks and kuffiyehs, and mounds of wheat and corn, and olives and oranges from the hill orchards, and complaining oxen and fat-tailed sheep. Where there is dust in the endless process of becoming mud and then again dust.