In Praise of Hatred

I was honoured to be asked to write the introduction to the English translation of Khaled Khalifa‘s third novel, In Praise of Hatred – set in Syria in the 1980s and essential background reading for the current tragedy. Four paragraphs of the introduction are reprinted below, and then Maya Jaggi’s review in the Guardian.

I was honoured to be asked to write the introduction to the English translation of Khaled Khalifa‘s third novel, In Praise of Hatred – set in Syria in the 1980s and essential background reading for the current tragedy. Four paragraphs of the introduction are reprinted below, and then Maya Jaggi’s review in the Guardian.

So how brave and necessary it was to write a fiction of the events. In our narrator’s harsh euphemism, Alawis are “the other sect” and the Ba‘ath Party is “the atheist party”, but the historical references are unmistakeable. Khalifa plays one of the noblest roles available to a writer: he breaks a taboo in order to hold a mirror to a traumatised society, to force exploration of the trauma and therefore, perhaps, acceptance and learning. He offers a way to digest the tragedy, or at least to chew on its cud. In this respect he stands in the company of such contemporary chroniclers of political transformation and social breakdown as Gunter Grass and JM Coetzee.

In purely literary terms as well as politically, the novel rises to a daunting challenge: how to represent recent Syrian history, which has often been stranger and more terrible than fiction.

For a start, it’s a perceptive study of radicalisation understood in human rather than academic terms. It accurately portrays violent Islamism as a modernist phenomenon, a response to physical and cultural aggression which draws upon Trotsky, Che and Regis Debray as much as the Qur’an, and contrasts it with the more representative Sufism of Syrian Sunnis.

Next, it examines the dramatic transformations of character undergone by people living under such strain, the bucklings and reformations, the varieties of madness. The characters here are fully realised and entirely flexible, even our bitter narrator, and their stories are told in a powerfully rhythmed prose which is elegant, complex, and rich in image and emotion. There is musicality too in the rhythm of the episodes, the subtle unfolding of the plot.

The Fall of the House of Asad

This review of David Lesch’s book was written for the Scotsman.

Until his elder brother Basil died in a car crash, Bashaar al-Assad, Syria’s tyrant, was planning a quiet life as an opthalmologist in England. Recalled to Damascus, he was rapidly promoted through the military ranks, and after his father’s death was was confirmed in the presidency in a referendum in which he supposedly achieved 97.29% of the vote. Official discourse titled him ‘the Hope.’

Propaganda aside, the mild-mannered young heir enjoyed genuine popularity and therefore a long grace period, now entirely squandered. He seemed to promise a continuation of his father’s “Faustian bargain of less freedom for more stability” – not a bad bargain for a country wracked by endless coups before the Assadist state, and surrounded by states at war – while at the same time gradually reforming. Selective liberalisation allowed for a stock market and private banks but protected the public sector patronage system which ensured regime survival. There was even a measure of glasnost, a Damascus Spring permitting private newspapers and political discussion groups. It lasted eight months, and then the regime critics who had been encouraged to speak were exiled or imprisoned. Most people, Lesch included, blamed the Old Guard rather than Bashaar.

“I got to know Assad probably better than anyone in the West,” Lesch writes, and this is probably true. Between 2004 and 2008 he met the dictator frequently. His 2005 book “The New Lion of Damascus” seems in retrospect naively sympathetic. He can be forgiven for this. Most analysts (me included), and most Syrians, continued to give Bashaar the benefit of the doubt until March 2011.

Save the Children in Za’atari Camp

Save the Children has released a report on the suffering of Syria’s children, based mainly on interviews with children in Jordan’s very basic Za’atari refugee camp. The Guardian reports on it here. I contributed to a discussion of the report on the BBC World Service’s World Have Your Say programme. My interjections come between thirteen and seventeen minutes.

Blasphemy

“Is the Prophet who is being insulted in Syria not the same Prophet who is being insulted in America?”

This video is not suitable for children nor for those of a nervous disposition. I include myself in the latter category. At first I couldn’t watch it, then I made myself do so in order to hear the words. Before the usual “Freedom? You want freedom?” the torturee is forced to declare that Bashaar al-Asad is his ‘lord’ (the Arabic word ‘rabb’, which means God). The violent (but very small) protests which have swept the Muslim world in response to a ridiculous low-budget smear of the Prophet Muhammad are in part the expression of a deeply humiliated people who remember Western support of Zionism and Muslim dictatorships, Western invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan, and so on. They are in part the result of the failure of Arab and Muslim dictatorships to build functioning education systems, and a symptom of a profound and generalised despair that requires wounded symbols through which to manifest itself. Most importantly, they are signals of an opportunistic power play by the extreme right-wing Salafist minority. It’s a case of extreme right-wing Islamophobes, Zionists, Coptic extremists and American Republicans on the one hand and extreme right-wing Islamists on the other, feeding off each other. The furore has made the ridiculous anti-Islam film a Youtube hit. Nobody would have heard of it had Egyptian Islamists not publicised it, and had the American ambassador to Libya, apparently a friend of the Arabs who was critical of US policy on Palestine, not been murdered. As with all the episodes in the ‘culture wars’, it’s an enormous diversion from the really serious issues. The torture video here was first pointed out by the Syrian activist Wissam Tarif. He asked a simple question. Where are the furious demonstrations against this blasphemy? Why have no Syrian embassies been burnt following the repeated bombing of mosques and churches, the murder, rape, torture and humiliation of tens of thousands of Syrian Muslims?

To Kill, and to Walk in the Funeral Procession

Updated with a postscript noting Robert Fisk’s obscene pro-regime propaganda while embedded with the regime army in Daraya, and the response of the LCCs to Fisk’s nonsense.

The Syrian regime is now perpetrating crimes against humanity at a pace to match its crimes in Hama in 1982 and at the Tel Za’atar Palestinian camp in 1976. All of Syria is a burning hell. Savage aerial bombardment (such as that causing the apocalypse here in Kafranbel, which held such beautifully creative demonstrations) and continuous massacres have raised the average daily death toll to well above two hundred, most of them in Damascus and its suburbs. The other day 440 people were murdered in twenty four hours.

The worst hit area has been the working class suburb of Daraya. I visited people in Darayya some years ago, and once bought a bedroom set for a friend’s wedding in the town. I remember it as a lively, friendly, youthful place. Last year Daraya became a cultural centre of the revolution. Ghiath Matar and others developed wonderful methods of non-violent protest there. When security forces arrived to repress demonstrations, Darayya’s residents handed the soldiers flowers and glasses of water. But Matar was murdered, and Daraya has been repeatedly raided, its young men detained and tortured, its women and children shot and bombed. Nevertheless, for some months the regime was kept out of Daraya. The town ruled itself in a civilised manner, successfully keeping a lid on crime and sectarianism.

The recent pattern is already well established (remember the massacre at Houla), but this time has played out on a larger scale. The regime bombed Daraya for days, mainly from artillery stationed on the mountains overlooking Damascus. Once any armed resistance had retreated, soldiers and shabeeha militia moved in, with knives and guns. This stage reminds one of Sabra and Shatila. It seems there was a list of suspected activists and resistance sympathisers, but the field executions included old men, women and children. About three hundred bodies have been counted so far, found in the street or in basements or in family homes.

World Have Your Say

Me, Jenan Moussa, Bilal Saab and others discuss recent developments in Syria on the BBC World Service’s World Have Your Say.

All Things Considered

Me discussing Syria’s Christians on BBC Radio Wales with Harry Hagopian, the lovely Nadim Nassar, and the strange English priest and admirer of the tyrant Christopher Gilham.

http://downloads.bbc.co.uk/podcasts/wales/atc/atc_20120805-1030a.mp3%20%20target=_blank

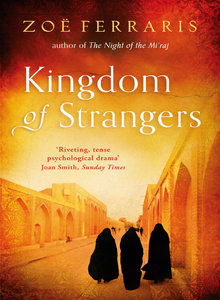

Kingdom of Strangers

This review was first published at the Guardian.

This review was first published at the Guardian.

“Surely” – a desperate character muses on his way to court – “there were a thousand other men like him who’d made mistakes enough to ruin their lives, their careers and their families, and yet surely those men had carried on, as had their families. There was room for everything in this vast, disordered place.”

The place is Jeddah, Saudi Arabia, depicted by celebrated crime writer Zoe Ferraris with sympathy and realism, and in all its complexity: through its text messages and mobiles, SUVs and shopping malls, its exorcist surgeries and women-only banks, plus the “forced meditation” of compulsory prayer. And the harsh worlds inhabited by immigrant workers. Migrant workers, female and male, constitute perhaps a third of the Saudi population, and they give this novel – Kingdom of Strangers – its title.

To start with, nineteen bodies are found in the desert. The carefully mutilated victims are immigrant women, Asians, and their corpes are arranged to convey a hidden message.

Enter Chief Inspector Ibrahim Zahrani, whose repertoire includes policeman’s intuition and Beduin trackers as well as forensic analysts and an American expert on serial killers.

Ibrahim is a liberal in his context, a rationalist, but he’s not squeamish, in his moments of pain, about applying violence to the deserving. His quiet suffering and basic decency would make him a figure of genuine tragedy if the plot didn’t rather unconvincingly spirit him out of danger at the close.

Summary for the Standard

This was first published by London’s Evening Standard (second story on the page).

In important ways, the regime has been collapsing for a couple of months. The Free Syrian Army – hundreds of militias made up of defected soldiers and volunteers – has liberated rural territory in the north and centre of Syria and controls sections of Homs and other cities. A steady stream of defections, including such prominent figures as General Manaf Tlass, has swollen the opposition.

Significantly, the regime has lost its support base in Damascus and Aleppo, where the arrival of refugees from other cities, terrible economic conditions and news of the Houleh massacre have provoked a wave of strikes and demonstrations.

Battles have raged in the suburbs. Now Operation Damascus Volcano has entered the capital. It’s an impressive show of coordinated popular and armed resistance, met by helicopter gunships, artillery fire and roving bands of thugs. The escalation renders the deadlocked international management of the crisis entirely irrelevant.

Blanket Thinkers

One of my infantile leftist ex-friends recently referred to the Free Syrian Army as a ‘sectarian gang’. The phrase may well come from Asa’ad Abu Khalil, who seems to have a depressingly large audience, but it could come from any of a large number of blanket thinkers in the ranks of the Western left. I admit that I sometimes indulged in such blanket thinking in the past. For instance, I used to refer to Qatar and Saudi Arabia as ‘US client states’, as if this was all to be said about them. I did so in angry response to the mainstream Western media which referred to pro-Western Arab tyrannies as ‘moderate’; but of course Qatar and Saudi Arabia have their own, competing agendas, and do not always behave as the Americans want them to. This is more true now, in a multipolar world and in the midst of a crippling economic crisis in the West, than it was ten years ago. Chinese workers undertaking oil and engineering projects in the Gulf are one visible sign of this shifting order.

The problem with blanket thinkers is that they are unable to adapt to a rapidly shifting reality. Instead of evidence, principles and analytical tools, they are armed only with ideological blinkers. Many of the current crop became politicised by Palestine and the invasion of Iraq, two cases in which the imperialist baddy is very obviously American. As a result, they read every other situation through the US-imperialist lens.

Beirut Three: Social Life

I’ve just come back from the Hay Literature Festival in Beirut. Literature Across Frontiers asked me to write three posts on the experience. Here’s the third.

At this year’s Karachi Lit Fest, Hanif Qureishi asserted that the purpose of such festivals was “to give writers a social life.” I concur wholeheartedly, but still I admit I was a little scared to go to Beirut and socialise there. This is because several Syrians had advised me to avoid speaking about the revolution while in the city, and to watch my back in areas controlled by Syrian regime allies. “They know who you are,” they muttered darkly.

But I was fine. At no point did I feel under any threat. I presume the warnings tell us more about the fear so successfully planted in Syrian hearts than they do about the capacity of the flailing regime to hunt down obscure writers. True, one Syrian slit another Syrian’s throat outside the Yunes Cafe just a couple of minutes’ walk from my hotel one night. Reports varied as to whether the killing was personally or politically motivated. And true, writer Khaled Khalifa’s arm was still in a sling after being broken by regime goons during the funeral of murdered musician Rabee Ghazzy back in May. Khaled, whose most famous novel ‘In Praise of Hatred’ is about to be published in English by Doubleday (I’m writing the introduction), is a warm and gentle man who smiles irrepressibly despite it all. He spoke fearlessly during his event at the Hay Festival. He’ll be back in Syria now. In Beirut I asked him why he didn’t stay outside, in safety. He said he can’t, he becomes scared for his friends and family when he’s outside.

I spent one inspiring evening with a group of Syrian revolutionaries, supporters of the Free Syrian Army who confound the stereotypes propounded by the regime and picked up on by certain infantile leftists. Far from being Salafists and tools of imperialism, these were secular men and women (one of Christian background) sharing a flat and ideas, drinking whiskey and mate, reflecting on the surging movement of the recent past and checking internet updates on the immediate present. They were well-informed, intelligent, and nuanced in their thinking (at one point we discussed the nature of evil and the complex question of individual culpability). They had seen nasty things, yet talking to them made me surprisingly buoyant. They believed they were winning their fight.

Beirut Two: Everyone in their Box

I’ve just come back from the Hay Literature Festival in Beirut. Literature Across Frontiers asked me to write three posts on the experience. Here’s the second.

I’ve just come back from the Hay Literature Festival in Beirut. Literature Across Frontiers asked me to write three posts on the experience. Here’s the second.

When a Scottish-based writer, an escapee from the perma-gloom, visits Beirut for a mere four days, he must prioritise his activities very carefully. As previously stated, I aimed first of all to immerse myself in the sea.

A small group of us hailed a cab to take us southwards down the coast to Jiyeh, where a beach had been recommended. Jiyeh wasn’t very far – we could still see Beirut jutting into the sea behind us – but it was still a good third of the way to the South and the troublesome border with Israel-Palestine.

Lebanon is a small, closely-packed country chopped again into still-smaller zones. Our driver (he was called Abdullah) inched us through the snarled traffic of central Beirut and past Tariq Jdaideh, a Sunni area loyal to the Hariri family, whose posters were prominent. Then along the edge of the Shi‘i southern suburb which was hit so brutally by Israel’s assault in 2006. Here Hizbullah controls one side of the road, with its pictures of Nasrallah and the late Ayatullah Fadlullah; the Amal movement rules over the other, shabbier side, where the pictures feature Nabih Berri, speaker of the Lebanese parliament. As the building density eased, banana plantations alternated with churches and seaside resorts. We sped up past Khalde, which had housed an illegal Druze port during the civil war fragmentation, and then Ouzai, which had housed an illegal Amal movement port. Inland, the Shouf mountains rose, the Druze heartland where the Junblatt family predominates. In this country, it seemed, everyone fitted into their specific box.

Beirut One: Dividing Lines

I’ve just come back from the Hay Literature Festival in Beirut. Literature Across Frontiers asked me to write three posts on the experience. Here’s the first.

I’ve just come back from the Hay Literature Festival in Beirut. Literature Across Frontiers asked me to write three posts on the experience. Here’s the first.

On the plane from Heathrow I sat next to an Armenian lady. She was born in Aleppo, Syria’s most cosmopolitan city, has lived in New Jersey for years, and is visiting Lebanon for a week, for her nephew’s wedding. I asked why she wasn’t staying longer; it’s such a long flight from the states after all. “Why not?” she replied. “Relatives and politics: these are two reasons not to stay long in the Middle East.”

Politics, which tends to suck in relatives, especially if you’re Armenian, or Palestinian, or any variety of Lebanese. We talked about her grandmother’s sister, a victim of the 1915 genocide of Armenians in Turkey, when somewhere between half and one and a half million people were murdered, either by massacre or by forced marches into the heat of the Syrian desert. Armenians call it ‘the Great Crime’.

The grandmother’s sister, a very little girl at the time, survived the march, but was separated from her family. She ended up outside Mosul, in northern Iraq, where she married a Beduin (“a man in a tent,” the Armenian lady said). She forgot her language but remembered her name and her Armenian identity. Whenever he went to town, her husband asked people to let him know if any Armenian turned up. Many years passed, and eventually an Armenian did turn up, and was directed to the tent. So the lost child was at last put in touch with the remnants of her family, and came to spend a month with them in Beirut. Then she returned to the tent and her Beduin life. She didn’t fit in the city.

In Dawn

As an apology for not posting anything for so long, I’m putting up this interview with me conducted by Muneeza Shamsie and published in Pakistan’s Dawn. There are a couple of inaccuracies: I spent a year and a few months in Pakistan in the early 90s, not two years, and it’s mainly been book reviews rather than political analysis that I’ve contributed to British newspapers.

Novelist, editor and journalist, Robin Yassin-Kassab has worked and travelled around the globe — in England, France, Syria, Saudi Arabia, Morocco, Oman and Pakistan. But his travels beyond Europe began with Islamabad. He arrived in the 1990’s at the invitation of a Pakistani friend and stayed for two years working as a journalist for an English daily. This winter he returned to Pakistan to conduct creative writing workshops at the Karachi Literature Festival and spoke with passion on the Arab Spring and the political situation in Syria.

In his critically acclaimed novel, The Road from Damascus (2009), Yassin-Kassab discusses multiculturalism, racism and radicalisation in Britain and the larger conflicts in the Middle East through the portrayal of Sami, a British Syrian, and Muntaha, his Iraqi-born wife. The novel examines debates between religious and secular concepts of Arab nationhood and comments on the use of state terror by totalitarian regimes.

During a trip to Damascus, Sami discovers an uncle who had been the victim of prolonged imprisonment and torture. Deeply disturbed, Sami returns to his wife but retreats from their matrimonial tensions, disappears from home and falls into rapid decline. The narrative builds in London in the aftermath of 9/11 and talks about Muntaha’s traumatic childhood, including her escape to Britain from Iraq with her father and brother.

Yassin-Kassab now lives in Scotland and contributes political analyses to The Guardian, The Independent, The Times and Prospect Magazine among others. He co-edits the website PULSE and the journal The Critical Muslim. He is working on his second novel.

Here he talks to Books&Authors about his novel, the writing process and the evolving situation in the Middle East.

The Milgram Experiment in Syria

It has thrown students out of top-floor windows. It has shelled cities from the land and from the air. It has raped women and men and tortured children to death. Now with the massacres at Howleh and Qubair – in which Alawis from nearby villages, accompanied by the army, shelled, shot and stabbed entire families to death – the Syrian regime has escalated its strategy of sectarian provocation. Here Tony Badran explains very well the sick rationale behind these acts.

To a certain extent the regime’s plan has already worked. Now it seems inevitable that sectarian revenge attacks will intensify. In general, sectarian identification is being fortified in the atmosphere of violence created by the regime and added to by the necessary armed response to the regime. Sectarian hatred will deepen so long as the regime survives to play this card.

The regime wants us to understand the conflict in purely sectarian terms. Many Syrians recognise this and are resisting it. At this impossibly difficult time it’s good to remember the Alawi revolutionaries, who are heroes, and crucial to the revolution, heroic in the way Jewish anti-Zionists are heroic.

What do I mean by heroic? A disproportionate number of Alawis owe their livelihood to the regime. To fight for a post-regime future means to fight for a future in which their community will be, at best, less favoured than at present. This takes moral and political courage. Many Alawis have grown up surrounded not, as most Syrians have, by anti-regime mutterings, but by the happy version. To break with this version requires a psychological transformation, something as big as growing up. More concretely, there are family pressures – and family is so important in Syria. Very many Alawis are employed in the security forces. If your uncle is an officer in the mukhabarat, therefore, you don’t find it easy to publicly oppose the regime. It takes courage to do so, and the kind of confidence in your own judgment which will allow you to discount the arguments of your elders and authorities. Only a few people have such strength. (Of course it takes much more strength to live in a Sunni neighbourhood being beseiged and bombed, but this is a different kind of strength.)