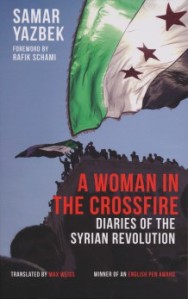

Woman in the Crossfire

‘A Woman in the Crossfire: Diaries of the Syrian Revolution’ by novelist Samar Yazbek is part journalism, part personal memoir, and all literature. It’s literature of the instantaneous sort, a staggered snapshot of the first four months of the revolution, a public history of “a country succumbing to the forces of death,” and an interior history too. Yazbek tells us about her headaches, her insomnia and Xanax addiction, her crying fits, her fears for her daughter and herself, her constant panic. How sometimes in the speeded-up context the rush of information precedes all feeling: “The daily news of killing,” she writes, “was more present inside of me than any emotion.”

‘A Woman in the Crossfire: Diaries of the Syrian Revolution’ by novelist Samar Yazbek is part journalism, part personal memoir, and all literature. It’s literature of the instantaneous sort, a staggered snapshot of the first four months of the revolution, a public history of “a country succumbing to the forces of death,” and an interior history too. Yazbek tells us about her headaches, her insomnia and Xanax addiction, her crying fits, her fears for her daughter and herself, her constant panic. How sometimes in the speeded-up context the rush of information precedes all feeling: “The daily news of killing,” she writes, “was more present inside of me than any emotion.”

Samar Yazbek has always been problematic. Having consecrated herself “to the promise of a mysterious freedom in life,” she left home (in Jableh, on the coast) at sixteen, later divorced her husband and lived in Damascus, a single mother, working in journalism and writing sexually controversial novels. When Syria rose up against the Asad regime she publically supported the victims and their cries for freedom. And she’s an Alawi, a member of the president’s largely loyalist sect, of a well-known family. As an unveiled and obviously independent woman, a secularist and daughter of a minority community, her support for the revolution proved the lie of regime propaganda, which characterised the uprising as Salafist from the start.

So leaflets slandering her were distributed in the mountains. She was called a traitor, made recipient of death threats, publically disowned by family and hometown. Naturally she was visited by the mukhabarat and made to experience, vicariously at least, the domestic wing of regime propaganda – for the theatre of blood is as important inside Syria as the projection of civilised moderation used to be abroad – by being walked through a display of meat-hooked and flayed torturees.

The Samar Yazbek of these diaries is an imposing presence but not one who crowds the reader. Indeed a reader who isn’t in Damascus, who hasn’t experienced the strangeness first hand (and what strangeness! – a known city, a home country, transforming into a death zone) requires a strong character through whom to experience and understand, just as he would if reading a novel. But beyond locating the reader, Yazbek more often plays her “favourite role, pretending not to know anything in order to learn everything,” and she gives most space over to the accounts of others.

Through these reports we learn of the horrors of detention and torture, of the pleasures and pains of protesting, of the plights of conscripts and refugees. Yazbek interviews secret sympathisers of the revolution, a state TV employee for instance, or a soldier who shot his own foot to escape the order to kill his countrymen, as well as committed revolutionary activists, the kind of people who are still very influential on the ground in Syria despite the inevitable arming of the revolution and the consequent rise of resistance militias. While the armed men fight, the activists are organising liberated and besieged areas.

One of the book’s most useful sections describes the early development of the Coordination Committees, the revolution’s backbone. Yazbek describes a spontaneous meritocracy in which talents are distributed into political, medical, media, even arts and culture committees, an organisational process entirely opposite to Asad’s corrupt, sectarian and nepotistic state. She also very usefully describes the non-ideological compromise secularist activists made with the religious culture of the masses, recognising religion’s centrality to many people’s experience of existence, as well as its obvious mobilisational power.

Her informants’ accounts illustrate how from the revolution’s earliest days the regime instrumentalised sectarian hatred, particularly in the coastal cities, Banyas, Jebleh and Lattakia, and the surrounding countryside, areas shared between Sunnis and Alawis. Rumours of roving Sunni mobs intent on murder were spread in the mountains and reinforced by false flag operations carried out by shabeeha. If this nonsense hadn’t largely worked, its memory would be comical. In Jebleh the alarm was frequently raised that an ‘infiltrator’ was at large in a neighbourhood, so the people would come out to catch him. When the same infiltrator was captured twice, each time in different neighbourhoods, a bystander was prompted to advise security to use different bait next time, if they still wished to be believed.

For the historian and analyst Yazbek’s diaries also provide important local information of a strategic nature, details often missed by newspaper articles, such as the fact that the Maydan and Qaboon areas of Damascus came out against the regime early because of the residents’ kinship ties to Dera’a, the revolution’s cradle.

But the main reason to read the book is for the immediacy and breadth of perspective (religious or not, Sunni, Alawi, Christian, of various class backgrounds) it offers, for the human element, and for its sense of shock:

“I stared into his eyes, which were like every other murderer’s eyes that have appeared these days, eyes I had never seen before in Damascus. How could all those murderers be living among us?”

It’s a narrative brimming with stark images. One, for example, of security forces attacking a funeral, shooting and critically injuring three pallbearers, causing the mourners to flee, leaving the coffin alone on the ground in an empty but blood-spattered street. It’d be a great image for a novelist to dream up, but reality got there first; reality in Syria outstrips imagination.

After four fraught months Yazbek and her daughter fled to Paris. She’s written about visits to liberated parts of Syria since, and like every Syrian inside or outside, like everyone connected to Syria, she sits and she wonders what terrors or glories the future might hold. “Fire scalds,” the book finishes. “Fire purifies. Fire either reduces you to ash or burnishes you. In the days to come I expect to live in ashes or else to see my shiny new mirror.”

The translation is by Max Weiss, and is excellent.

[…] leave a comment » […]

Woman in the Crossfire « band annie's Weblog

December 26, 2012 at 9:02 pm

When Samar came to Cambridge, we had the chance to see her face and hear her talk about her story. Picked up a copy of the book. It was riveting – though in translation. I imagine in Arabic- it would be even more stunning. A very very sharp and personal read- totally recommended for everyone.

Zenobia

January 7, 2013 at 6:19 am

[…] is a great project which I saw at work on the ground. It was set up by novelist and revolutionary Samar Yazbek , and is based in Paris. To donate:RIB de la banque LA BANQUE POSTAL. ASSOCIATION SORYAT POUR LE […]

Help the Syrian People | Marpm

May 27, 2014 at 12:57 pm

[…] Posted on Qunfuz […]

Book Review: Women in crossfire, Diaries of the Syrian Revolution | 4 Change

October 12, 2018 at 9:37 am