Archive for March 2025

The End of the Fairy Tale

An edited version of this piece was published at UnHerd. I disagree with the headline there – Syria Can’t Escape War – though at present it looks like the cycle of violence will keep on rolling. Along with the Assadist violence and the sectarian killings by men linked to the new authorities, there have been deals with the SDF and representatives of the Druze. It’s true that these are only preliminary steps – that the SDF deal was spurred by the American desire to withdraw, for instance, that the PKK may seek to quash part of the deal (SDF integrating into national army) and Damascus may seek to renege on another (decentralization). But if Syrians keep working intelligently, the country can indeed escape war, and build something better. Anyway, here’s the piece:

The sudden collapse of the Assad regime on December 8 2014, without any civilian casualties, felt like a fairy tale. Syrians had feared that the Assadists would make a last stand in Lattakia, the heartland of the regime and of the Alawite sect from which its top officers emerged. Many also feared there would be a sectarian bloodletting as traumatised members of the Sunni majority took generalised revenge on the communities which had produced their torturers. None of that happened then. But some of it has now. On March 6, an Assadist insurgency killed hundreds in Lattakia and other coastal cities. Then men associated with the new authorities, as well as suppressing the insurgency, committed sectarian atrocities, summarily executing their armed opponents, and killing well over a hundred Alawite civilians.

This is the first sectarian massacre of the new Syrian era, and it casts a fearsome shadow over the future. The revolution was supposed to overcome the targeting of entire communities for political reasons. Now many fear the cycle will continue.

The previous regime was a sectarianizing regime par excellence, both under Hafez al-Assad, who ruled from 1970, and under Hafez’s son Bashar, who inherited the throne in 2000. This doesn’t mean that the Assads attempted to impose a particular set of religious beliefs, but that they divided in order to rule, exacerbating and weaponizing fears and resentments between sects (as well as between ethnicities, regions, families, tribes). They carefully instrumentalised social differences for the purposes of power, making them politically salient.

The Assads made the Alawite community into which they were born complicit in their rule, or at least, to appear to be so. Independent Alawite religious leaders were killed, exiled or imprisoned, and replaced with loyalists. Membership in the Baath Party and a career in the army were promoted as key markers of Alawite identity. The top ranks of the military and security services were almost all Alawite.

In 1982, during their war against the Muslim Brotherhood, Assadists killed tens of thousands of Sunni civilians in Hama. That violence pacified the country until the Syrian Revolution erupted in 2011. The counter-revolutionary war which followed can justifiably be thought of as a genocide of Sunni Muslims. From the start, collective punishment was imposed on Sunni communities where protests broke out, in a way that didn’t happen when there were protests in Alawi, Christian or mixed areas. The punishment involved burning property, arresting people randomly and en masse, then torturing and raping those arrested. As the militarization continued, the same Sunni areas were barrel-bombed, attacked with chemical weapons, and subjected to starvation sieges. Throughout the war years, the overwhelming majority of the hundreds of thousands of dead, and of the millions expelled from their homes, were Sunnis.

Alawi officers and warlords were backed in this genocidal endeavour by Shia militants from Lebanon, Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan, all of them organized, funded and armed by Iran. These militias – with their sectarian flags and battle cries – were very open about their hatred of Sunnis.

The worst of sectarian provocations were the massacres perpetrated in towns in central Syria, especially in 2012 and 2013, places like Houla, Tremseh, and Qubair. The modus operandi was that the regime’s army would first shell a town to make opposition militias withdraw, then Alawi thugs from nearby towns would move in to cut the throats of women and children. It’s important to note that these were not spontaneous assaults between neighbouring communities, but were carefully organized for strategic reasons. They were intended to induce a backlash which would frighten Alawites and other minorities into loyalty. This fitted with the regime’s primary counter-revolutionary strategy. Early on it had released Salafi Jihadis from prison while rounding up enormous numbers of non-violent, non-sectarian activists. For the same reason, it rarely fought ISIS – which in turn usually focused on taking territory from the revolution.

Read the rest of this entry »The Tragic Arc of Baathism

An edited version of this essay was published by Unherd.

As well as the most persistent, the Syrian Revolution has been the most total of revolutions. Starting in early 2011 and culminating unexpectedly in December of 2024, it – or rather, the Syrian people – managed to oust not only Bashar al-Assad, but also his army, police and security services, his prisons and surveillance system, and his allied warlords, as well as the imperialist states which had kept him in place. The revolutionary victory marked the end of a dictatorship which had lasted 54 years (under Bashar and his father, Hafez), and also the final, belated death of the 77-year-old Baath Party, once the largest institution in both Syria and Iraq.

Founded in Damascus in April 1947, the Arab Socialist Baath Party went through three major stages, each closely related to the vexed political history of the Arab region. The first stage was one of abstract and unrealistic ideals. Baathism was the most enthusiastic iteration of Arab nationalism. Whereas Egyptian president Gamal Abdul Nasser understood the Arab world as a strategic depth for Egypt and a field in which he could exert his own influence, the Baathists had an almost mystical apprehension of the Arabs as a nation transcending historical forces, one which had a “natural right to live in a single state.”

The founding figures were Syrians who had immersed themselves in European philosophy (Bergson, Nietzsche and Marx) while studying at the Sorbonne in Paris. Two of the three founders were members of minority communities, and it’s useful to think of Baathism as a means of constructing an alternative identity to Islam. While Salah al-Din Bitar was a Sunni Muslim, Michel Aflaq was an Orthodox Christian and Zaki Arsuzi was an Alawi who later adopted atheism. The three mixed enlightenment modernism with romantic nationalism. Arsuzi, for instance, believed Arabic, unlike other languages, to be “intuitive” and “natural”. And Aflaq turned the usual understanding of history on its head. He considered Islam to be a manifestation of “Arab genius”, and deemed the ancient pre-Islamic civilizations of the fertile crescent – the Assyrians, Phoenicians, and so on – to be Arab too, though they hadn’t spoken Arabic.

Like other grand political narratives of the 20th Century, Baathism was an attempt to repurpose religious energies for secular ends. The word Baath means “resurrection”. The party slogan was umma arabiya wahida zat risala khalida, or “One Arab Nation Bearing an Eternal Message”, which sounds strangely grandiose even before the realization that umma is the word formerly used to describe the global Islamic community, and that risala is used to refer to the message delivered by the Prophet Muhammad.

The party’s motto – “Unity, Freedom, Socialism” – referred to the desire for a single, unified Arab state from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Gulf in the east, and from Syria in the north to Sudan in the south. The Arab state should be free of foreign control, and should construct a socialist economic system.

This dream was spread by countryside doctors and itinerant intellectuals. In those early days, the leadership consisted disproportionately of schoolteachers and the membership of schoolboys. In 1953, however, the party merged with Akram Hawrani’s peasant-based Arab Socialist Party. This brought it a mass membership for the first time, and it came second in Syria’s 1954 election.

By then, episodes of democracy were becoming more and more rare. Since Colonel Husni al-Zaim’s March 1949 coup – the first in Syria and anywhere in the Arab world – politics was increasingly being determined by men in uniform. The most significant of these soldiers was Nasser, who seized power in Cairo in 1952, then became a pan-Arab hero when he confronted the UK, France and Israel over the Suez canal in 1956.

Read the rest of this entry »Citizenship or Sectarian Splintering

A slightly different version of this was published at the New Arab.

The fascist threat is by no means over in Syria, and neither is the revolution.

The showdown between irreconcilable Assadists and the country’s new rulers which didn’t erupt on December 8 last year is happening now. Worse, the attendant sectarian breakdown which Syrians feared may be underway.

On the sixth of March, Assadists in the coastal areas launched coordinated attacks on Syrian security forces, killing over 400. Snipers also attacked and killed civilians, killing hundreds. Hospitals and ambulances were targeted, and highways were closed by gunfire.

The violence was met by a massive popular response. In cities across Syria demonstrations came out in support of the government and to demand the rapid suppression of the Assadists. People rejected absolutely the idea of returning to the terrible past of torture chambers and barrel bombs. They also expressed fury at the Assad regime’s “remnants”, as they are known, for refusing the reconciliation offered. Despite their extremist background, the new authorities had surprised many Syrians by their pragmatic, intelligent approach to the old regime, offering an amnesty to all fighters except the top level war criminals, and assuring people of all sects and ethnicities that their rights would be assured. Syrians hoped that Assadists, and the Alawite community from which many emerged, would, in turn, accept the wrong they had done the country, and seek to make amends. Instead they were attacking hospitals.

Tens of thousands of angry men rushed to the coast to support the government. As well as convoys of pro-government militia, armed civilians joined the flood, despite an interior ministry statement asking citizens not to engage.

Though fighting still continues, government forces rapidly regained control over urban centres. But abuses against Alawite civilians risk turning this immediate victory into a longer-term defeat.

There were numerous field executions of Assadist fighters. Far worse, the reliable Syrian Network for Human Rights says at least 125 civilians were summarily executed in various locations. This – the first massacre perpetrated by men associated with the new authorities – is a disaster.

Read the rest of this entry »A Background of Blood

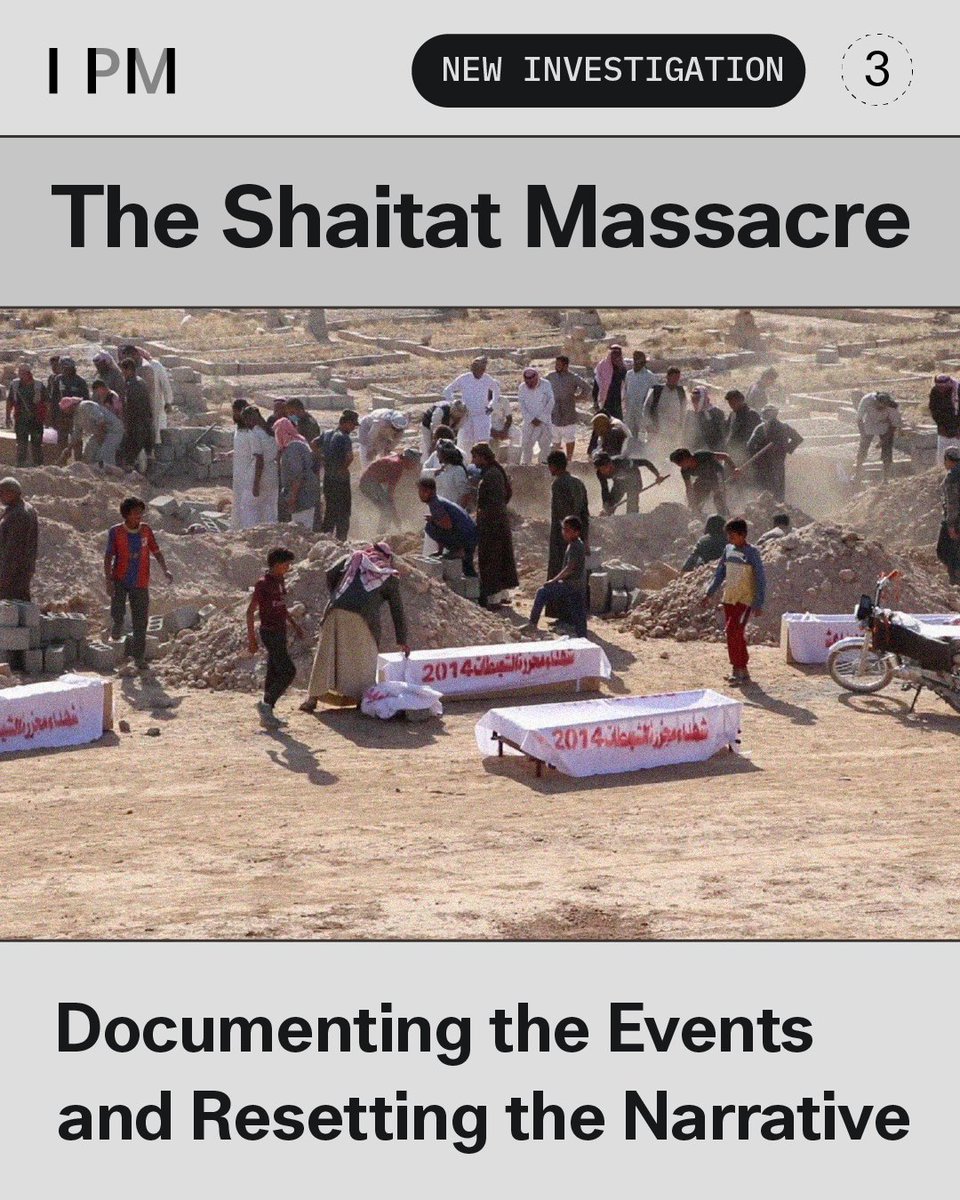

The ISIS Prisons Museum has produced the most comprehensive study yet of the 2014 Shaitat Massacre, the worst ISIS atrocity in Syria. The focus on the massacre includes witness testimonies, 3D prison tours, investigations into some of the dozens of prisons established in the Shaitat areas, and a detailed report on the killing and mass displacement of the clan and the looting and destruction of its property. The report is by far the most serious treatment yet of the events. It’s written by Sasha and Ayman al-Alo, and can be read here.

ISIS violence didn’t drop from the skies. It emerged from a context of massacres in Syria and Iraq perpetrated by the Assad regime, the Saddam Hussein regime, and various actors in the Iraqi and Syrian civil wars, including US troops and sectarian Shia militias. I have written a text to give this context. It’s called A Background of Blood, and can be read here.