Archive for the ‘book review’ Category

The Gulf Between Us

Another book review, fairly horribly edited by the Guardian. Here’s the unedited version:

The Arab world’s bestselling novel of recent years has been Alaa Al Aswany’s “Yacoubian Building”, which features a gay journalist, a corrupt minister, and sexual abuse in police cells. The very grown-up film of the book has reached a huge audience. Arabic novels on sale in the Gulf discuss taboos from pre-marital romance to sectarian conflict and slavery. Meanwhile, Al-Jazeera broadcasts from Qatar, offering the Arabs a range of political debate which shames the BBC, and which would have been unthinkable twenty years ago. Satellite and the internet have effectively finished the Arab age of censorship. As for books in English, the ‘Arab World’ sections of many Gulf bookshops could be renamed ‘Harem Fantasy for Whites’, concentrating disproportionately on more or less fraudulent revelations of the “Princess” variety. So long as it sells, very nearly anything goes.

Given the new level of official Arab tolerance, it was surprising to hear that Geraldine Bedell’s “The Gulf Between Us”, a romantic comedy narrated by a middle-aged Englishwoman, had been banned from the International Festival of Literature in Dubai, and this because the novel contains a ‘gay shaikh’. Both author and publisher cried censorship, plunging the festival – Dubai’s first – into a swamp of bad publicity. Margaret Atwood cancelled her appearance.

A few days after the damage had been done, the truth came out: the book hadn’t been banned. Like many others, it was not selected in the first place. Maragaret Atwood regretted her cancellation.

Stranger to History

A book review of Aatish Taseer’s “Stranger to History: A Son’s Journey Through Islamic Lands” for the Guardian.

Aatish Taseer grew up in secular, pluralist India. His early influences included his mother’s Sikhism, a Christian boarding school, and He-Man cartoons. Nagging behind this cultural abundance, however, was an absence: of his estranged father, the Pakistani politician Salmaan Taseer.

The best of “Stranger to History” is the “Son’s Journey” of the subtitle: the movement towards – and away from – his father’s world. Taseer describes the embarrassment, frustration and occasional joy of meeting his father and half-siblings, and of approaching a cultural and national identity which painfully excludes him. Alternating with this story is a more generalised journey into Islam, from the Leeds suburb which produced the 7/7 bombers, through Istanbul, Damascus and Mecca, to Iran and Pakistan. On the way Taseer observes the ‘cartoon riots’, is interrogated by Iranian security officials, and watches the response in his father’s Lahore home to Benazir Bhutto’s assassination. The writing is elegant and fluent throughout, the characters skillfully drawn.

Four Solutions

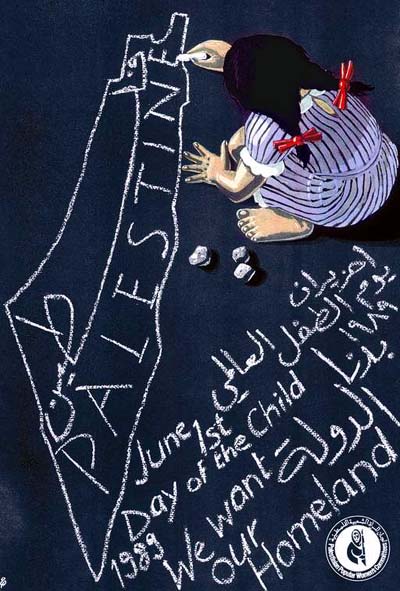

This was published at The Palestine Chronicle.

I do not hate (Israelis) for being Jewish or Israeli but because of what they have done to us. Because of the acts of occupation. It is difficult to forget what was done to us. But if the reason for the hate will not exist, everything is possible. But if the reason remains, it is impossible to love. First we must convince in general and in principle that we have been wronged, then we can talk about 67 or 48. You still do not recognize that we have rights. The first condition for change is recognition of the injustice we suffered.”

– Said Sayyam, martyred in Gaza January 2009, to Ha’aretz, November 1995.

All Palestine is controlled by Zionism. The Palestinians (not counting the millions in exile) are half the population of Israel-Palestine, but they are victims of varying degrees of apartheid. The Jewish state has already lost its Jewish majority, and is more hated by the Arab peoples than at any time in its brief, violent history. Let’s take it as given that continuation of the present situation is untenable for everyone concerned. We need a solution.

Two Reviews

Two reviews, one harsh and critical, one brief and bright.

I met Nadeem Aslam in Southampton, and spent an evening and a morning having wonderful conversations with him. When I told him I’d written a bad review of his latest book (half of it is bad) for the National (in Abu Dhabi) he was not in the least bitter, not even for a moment. I am not such a successful human being. I would have been convulsed with rage and venom for at least three hours, and then ill with it for weeks. He just wanted to know why I didn’t like the book. Well, it’s partly the politics, and quite a lot to do with characterisation. Then my review may be fierce precisely because I think he’s a major writer, and therefore fair game. (But I don’t think he’s fair game after meeting him, such a lovely man he is; I hang my head in shame). The negativity of the review may also have something to do with me responding to my own perceived failures as a writer.

And damn, they pay you to squeeze out an opinion, so opinionate is what you do.

The problem with writing a book review after you’ve had a book published is that it seems as if you’re suggesting you could outwrite the writer you’re criticising. Ironically, now that I should be more qualified to write about novels, I feel less qualified. Or at least worried that I’m setting myself up. Anyway.

Dawkins or McIntosh

I am increasingly infuriated by religious claims to certainty and by religious attempts to close down free thought (I’m not talking about high profile attacks on writers or cartoonists here, which have more to do with power politics than theology, but simply the resort to ‘it’s true because God says so’). Although some leftist and anti-imperialist Islamist groups have achieved great things, I find the current fashion for religious politics in the Arab world to be a dead end. Simple-minded slogans like ‘Islam is the solution’ are no solution. An analysis of contemporary disasters based primarily on class and state and corporation could conceivably provide grounds for unity and solidarity; political action based on Sunni or Shia myths will ultimately only help the empire to divide and rule; it will also empower rulers and institutions hiding behind religious cover. It is sad to watch the Muslims becoming more and more religious as they gallop further into social, economic and environmental catastrophe.

The rise of ugly modernist forms of religion is not confined to the Muslim world. Everywhere, the death of traditional religion has spawned a million poor substitutes. Under the pressure of traumatic social change, and almost always of war, traditional forms of Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism have morphed into Zionism, neo-conservatism, Bible-belt evangelical-nationalism, fascism, Stalinism, Ba’athism, Wahhabi-nihilism, state-Hindu chauvinism and Maoism. And fundamentalist atheism.

Egyptian Novels

In the contemporary Arab world, Bilad ash-Sham, or the Levant, surely comes first for poetry. Whether you’re looking for Muhammad Maghout’s bitter satire, anti-romanticism, and defence of the poor and the peasants, or for Mahmoud Darwish’s lyrical nationalism — whether you appreciate the modernist obscurity of Adonis or the powerful simplicity of Nizar Qabbani; you will turn to Syria and Palestine for your verse fix. The Arabs certainly do. For poetry in the Middle East isn’t the elite preoccupation it has become in the West. Taxi drivers and market men will quote you snippets of Qabbani’s love poetry or angry anti-occupation verse according to their temperament and the twist of the conversation. Even the illiterate may know some Qabbani from hearing it quoted in the café or crooned by the Iraqi singer Kazem as-Saher, with orchestral accompaniment. When Arab rappers want to express hardcore identity, they proclaim: “I’m an Arab like Mahmoud Darwish!” (the ‘Dam’ crew from Palestine.) That’s how uncissy Arab poetry is.

But for the Arabic novel, a genre which is only a century old (although there are much earlier precursors), the action is centred in Egypt, unsurprisingly – Egypt with its huge population and its indefinable, unmeasurable metropolis.

The most famous of Egyptian novelists is Naguib Mahfouz. Amongst the Arabs his books are bestsellers in garish covers, and many have been made into classic films. His international reputation was sealed when he became the first Arab to win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1988. Reflecting changes in 20th century Arab reality, his style developed from heroic through realist to magical realist or romantic symbolist.

“Maps for Lost Lovers” and writerly responsibility

Update 2015: With the passage of time, much of this review embarrasses me. So people and perspectives change. My current view is better summed up by my words at the 2015 Shubbak festival, which Brian Whitaker reports:

There is a beautiful novel called Maps for Lost Lovers by Nadeem Aslam who is Pakistani-British, and I would recommend that everybody reads the novel as a work of literature because it is beautifully, beautifully written and characterised.

It works as a novel, but there is no good Muslim character in it. They are real characters and you can sympathise with them even when they are doing horrible barbaric things. But they are all doing horrible barbaric things from the moment they get up in the morning, and its the kind of horrible barbaric things that British Pakistanis do that you read about in the Sun newspaper.

So of course there is an issue, but we cant tell Nadeem Aslam that he’s a representative British Pakistani writer and therefore he has to write a nice version of British Pakistanis in order to educate the white population that some of them are all right. He’s writing what he wanted to write about and what was real for him, and he did it really well. I think the critique should focus on the social context. It’s not Nadeem Aslam’s fault so much as the Sun newspaper’s fault.

And here’s the thing I originally wrote:

I’ve recently read Nadeem Aslam’s finely-constructed and richly metaphorical novel “Maps for Lost Lovers”, which portrays a British Pakistani community and its rigid boundaries over a year of daily life and crisis. Save for some occasionally unconvincing dialogue, the writing is beautiful and poetic. Unlike, for example, Martin Amis, Aslam respects his characters, who are well-rounded and complex enough to evoke sympathy even when they behave badly. He shows them busy with gossip, work, poetry – and plenty of murder. For example, a book shop owner is murdered for money by his relatives in Pakistan. At the heart of the book, Chanda and Jugnu are murdered by Chanda’s brothers for ‘living in sin.’ Chanda wants to divorce her husband so she can marry her lover, but her husband has disappeared for years, and she doesn’t know where to. Another girl is murdered by a ‘holy man’ during exorcism-beatings. And so on: a litany of crimes motivated by ‘honour’ and superstition.

One subplot revolves around a woman being forced by sharia law to marry another man before returning to a husband who has divorced her once while drunk. The actual regulation is this: if a man divorces his wife THREE times he cannot remarry her unless she has been married to someone else and that marriage has also collapsed. This is generally understood as a warning to husbands not to divorce their wives without considering the consequences. Furthermore, a divorce announced when the husband is angry or intoxicated is not recognised. As for the stranded Chanda, sharia would automatically grant her a divorce if her husband disappeared for a day longer than a year. Fair enough, Aslam is writing about uneducated people’s partial and skewed understanding of their religion, or of their confusion of tradition and religion, but this point will be lost on non-Muslim readers.

The Reluctant Fundamentalist

I’ve now read three September 11th novels, by which I mean novelistic responses to the issues raised by the attacks. The first was ‘Saturday’ by Ian McEwan. I usually feel somewhat cheated by McEwan’s novels, and this was no exception. He goes to such trouble to develop characters, setting and plot, raising your expectations to such a pitch that you feel you’re about to learn something unforgettable about life and human beings, and then it all fizzles out. ‘Saturday’ covers a day in the life of a London doctor called Henry Perowne. The day begins with Perowne worrying over a mysterious plane in the sky, wondering if it’s going to fly into a London landmark. Later he avoids the huge demonstration against the approaching invasion of Iraq. Perowne wonders how he feels about it all, comes to no conclusion, goes to play squash. He has an altercation with a thuggish person who scratches the paint from his car, and in the evening the same thug breaks into his house like a symbol of the intrusive messy world. I’ve forgotten how it ends. McEwan has been attacked for being a neo-conservative, or a liberal interventionist, or just as hopelessly complacent and bourgeois as his protagonist, but he has defended himself by pointing out that McEwan is not Perowne – an obvious truth. If we start blaming authors for what their characters say we end up like the fools in Egypt who demonstrated against Haider Haider’s novel ‘A Banquet of Seaweed’ (waleema li-‘ashaab al-bahr) because one of Haider’s characters – who later commits suicide – expresses atheistic beliefs. Nevertheless, it’s a shame that McEwan’s treatment of the post-September 11th world focusses only on Western self-absorption. What the events require is a new engagement with the darknesses and resentments of the world beyond our narrow conception of it, a new sense of the interconnections of the West and elsewhere, for better and for worse.

Then I read John Updike’s ‘Terrorist’, which I’ve previously discussed on this blog (http://qunfuz.blogspot.com/2006/11/updikes-terrorist.html ). My great respect for Updike as a writer perhaps made me too charitable in that evaluation. If anybody hasn’t read his series of ‘Rabbit’ novels, I strongly recommend them, for their wonderful style, their tragi-comedy, and for their vast scale which encompasses key moments in American history as well as in Harry ‘Rabbit’ Angstrom’s life. In these books Updike is clearly writing about what he knows and understands. In “Terrorist”, he clearly isn’t. His main protagonist, despite being mixed-race and mixed-up, is a stereotype, and so are all the Arabs and Muslims in the book – either dirty and threatening, or ‘good niggers’ who ardently support the attack on Iraq and report to the CIA. Nothing new is said about the motivations of anti-American terrorism or about the effect of the American empire on the world. Updike’s analysis goes no further than Martin Amis’s. He sees the causes of conflict to be sexual, not political, and believes that America is targetted as a result of its supposed moral degeneracy. But Muslims haven’t attacked the bikini beaches of Brazil, and such ‘analysis’ is as self-congratulatory as Henry Perowne’s bourgeois complacency.

Last night I finished ‘The Reluctant Fundamentalist’ by Mohsin Hamid. This is a simpler novel than the two described above, and is stylistically unremarkable. It is, however, a genuine consideration of real issues raised by September 11th. In its organisation and the cumulative metaphorical power of its subplots it is much more than competent. It is a confessional narrative, told by a Pakistani to an American in a restaurant in Lahore. The anguished first-person self-revelation is reminiscent of Dostoyevsky’s ‘Notes From Underground’, but Hamid’s Changez is a fundamentally balanced character. It’s the times, and the empire, that are out of joint, and Changez’s story is of righting himself by retreating from America. Educated at Princeton and working for a company which values businesses due to be sold off and stripped, Changez finds himself smiling when he sees TV reportage of the twin towers falling. This prompts a deepening examination of his identity, his allegiances, and his relationship with America. Parallels are implied between Muslim countries and the doomed employees of the companies Changez evaluates. The key here is not religion, but corporate capitalism and traumatic economic change. Changez’s boss Jim says, “We came from places that were wasting away.” He means, on the one hand, Pakistan, and on the other, old industrial America. ‘The Reluctant Fundamentalist’ is a catchy but not very apt title. There is very little theology in the book. By the end of the story Changez is not at all an Islamist, but discovers he has to oppose the corporate American empire in order to remain mentally and morally healthy.

There’s plenty of on-target comment about American reaction to September 11th. Like this: “I had always thought of America as a nation that looked forward; for the first time I was struck by its determination to look back. Living in New York was suddenly like living in a film about the Second World War; I, a foreigner, found myself staring out at a set that ought to be viewed not in Technicolour but in grainy black and white. What your fellow countrymen longed for was unclear to me – a time of unquestioned dominance? of safety? of moral certainty? I did not know – but that they were scrambling to don the costumes of another era was apparent. I felt treacherous for wondering whether that era was fictitious, and whether – if it could indeed be animated – it contained a part written for someone like me.”

The attack on the empire makes Changez aware of America as an empire. The final straw for him is when he hears someone describing the Janissaries, the Christian slaves taken as boys from their parents by the Ottoman empire and turned into an elite warrior class to defend the sultan. Is Changez a latter-day reversed Janissary?

In an effective subplot, Changez has an almost-girlfriend who is obsessed by the memory of her dead boyfriend. In her depression, “She glowed with something not unlike the fervour of the devout.” Themes of nostalgia and commingled, confused identities seep into other parts of the novel, where they are relevant to Changez, Pakistan, and America. These are the correspondences and suggested patterns that novel writing is all about. ‘The Reluctant Fundamentalist’ deals profoundly with politics without needing to limit itself to political discourse, and so succeeds as a novel. The novel is the most holistic form there is, in that it treats spirituality, identity, sex, politics, and so on, without drawing ideological lines between them. In that respect, the novel is a specimen of life.

Mohsin Hamid is a Pakistani who studied and worked in America and now lives in London. He has the cross-cultural experience to write a novel like this. But is it ridiculous to expect a more monocultural Anglo-Saxon writer to approach similar themes – of empire and resistance, of defensive nostalgia and confident self-reinvention – without resorting to stereotype and media cliché? Is a broader perspective really so difficult?

Updike’s Terrorist

John Updike, upon whom I would bestow grand titles such as, possibly, Greatest Living Writer in English (now that Bellow is dead), has written a topical novel called ‘Terrorist.’ The terrorist of the title is eighteen-year-old Ahmad Ashmawy Molloy, the confused and bitter American son of an Irish-American mother and absent Egyptian father.

Ahmad starts the novel as a schoolboy, and then is guided by a malign imam to give up his studies to become a truck driver (ignoring the more wholesome advice of guidance counsellor Jack Levy, a worldly, unbelieving Jew). Before long Ahmad drives his truck into a terrorist plot.

Updike, in his usual present tense, observes acutely and describes intensely. His beautifully rhythmed prose balances psychological analysis and social comment, the internal and the external. His digressions are eloquent and well-placed. Updike criticises in passing the black and white solutions of fundamentalist Christianity and the Black Muslims as well as al-Qa’ida style Islam, and diagnoses as the cause of these fundamentalisms the loss of direction and hollowness of a hedonist, consumerist society. Although Updike doesn’t speak directly. We find his position in the midpoint between his ironising distance from and sympathy for the perspectives of the characters through whom the narrative is focalised. His easy shifts between these perspectives is done professionally. There is a professional’s handling of detail too. For instance, Ahmad feels his beloved Excellency truck is a part of him, and responds badly to the ugly truck he will drive on the day of the ‘operation.’ It looks, like him, dispensable.

What’s Wrong With Travel Writing

I’ve recently read “Cleopatra’s Wedding Present” by Robert Tewdwr Moss, a well-written account of travels through Syria in the late 1990s. Moss is an evocative and sensuous writer. His sense of place and time is highly accurate: I immediately recognised the streets he described, and wanted to tell him how things have changed. (But it’s impossible to tell Moss anything now. He was stabbed to death by a rent boy in London shortly after finishing this book).

The strength of characterisation – of Syrians and foreign tourists – in the book suggests that Moss would have made a great satirical novelist. There are also strong set pieces on some of the archeological highlights of Syria, such as Queen Zenobia’s desert city of Palmyra, Saladin’s castle in the green Lattakian mountains, and the ‘dead cities’ around Aleppo – Byzantine settlements which were suddenly and mysteriously vacated, leaving mosaics, churches and olive presses for archeologists to puzzle over.