Five Year Reflection

Russian bombing in the eastern Ghouta. picture from Anadolu Agency

The Guardian asked ten Arab writers to reflect on the revolutions five years on (or in). My piece is here below. To read the rest too (including Alaa Abdel Fattah from Egyptian prison, Ahdaf Soueif, and notable others), follow this link.

Five years ago the Guardian asked me to evaluate the effects of the Tunisian uprising on the rest of the Arab world, and specifically Syria. I recognised the country was “by no means exempt from the pan-Arab crisis of unemployment, low wages and the stifling of civil society”, but nevertheless argued that “in the short to medium term, it seems highly unlikely that the Syrian regime will face a Tunisia-style challenge.”

That was published on January 28th. On the same day a Syrian called Hassan Ali Akleh set himself alight in protest against the Assad regime in imitation of Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation in Tunisia. Akleh’s act went largely unremarked, but on February 17th tradesmen at Hareeqa in Damascus responded to police brutality by gathering in their thousands to chant ‘The Syrian People Won’t Be Humiliated’. This was unprecedented. Soon afterwards the Deraa schoolboys were arrested and tortured for writing anti-regime graffiti. When their relatives protested on March 18th, and at least four were killed, the spiralling cycle of funerals, protests and gunfire was unleashed. Syria not only witnessed a revolution, but the most thoroughgoing revolution of all, the one that has created the most promising alternatives, and the one that has been most comprehensively attacked.

Still More Talking

And if you follow this link, and listen from 40 minutes till the end, you’ll hear me talking On BBC Radio 4’s ‘The World Tonight’ about Syria’s revolution and war. I was invited because our book Burning Country has been released. It tells the Syrian people’s stories first and foremost, before examining the global responses and results. We feel this drama has been very badly reported in the main, and we hope the book will fill some important gaps. So please read it.

Talking about the Councils

If you follow this link you’ll hear me talking on BBC World Service radio (‘Newshour’) about Syria’s revolutionary councils, decentralisation, refugees, and the ‘peace process’ illusion.

(I made a mistake here. I said Syrians need at least one or two hundred dollars to escape Syria. Slip of the tongue. I should have said they need one or two thousand.)

Burning Country UK Events

Thanks to assistance and inspiration from Syrian activists, fighters, journalists, doctors, artists and thinkers, our book ‘Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War‘ is published on January 20th, and launched that evening at Amnesty International in London. In the following days and weeks I’ll be speaking about the book at other venues in London, and in Nottingham, Manchester, Lancaster, Glasgow and Edinburgh. A list of events below (and we’ll be in the US in April).

Thanks to assistance and inspiration from Syrian activists, fighters, journalists, doctors, artists and thinkers, our book ‘Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War‘ is published on January 20th, and launched that evening at Amnesty International in London. In the following days and weeks I’ll be speaking about the book at other venues in London, and in Nottingham, Manchester, Lancaster, Glasgow and Edinburgh. A list of events below (and we’ll be in the US in April).

First, please read the endorsements, of which we’re very proud:

‘For decades Syrians have been forbidden from telling their own stories and the story of their country, but here Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila al-Shami tell the Syrian story. Their words represent the devastated country which has denied them and their compatriots political representation. Burning Country is an indispensable book for those who wish to know the truth about Syria.’ – Yassin al-Haj Saleh

‘Burning Country is poised to become the definitive book not only on the continuing Syrian conflict but on the country and its society as a whole. Very few books have been written on ‘the kingdom of silence’ that effectively capture how we all got here while not omitting the human voice, the country’s heroes and heroines — a combination that is rare but essential for understanding the conflict and its complexities. Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila Al-Shami have written a must-read book even as the conflict still rages to understand what happened, why it happened and how it should end.’ – Hassan Hassan, co-author of ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror (New York Times bestseller), Associate Fellow, Chatham House, London

Fighting Daesh at the Frontline Club

Alongside BBC correspondent David Lloyn; Richard Spencer, Middle East editor of the Daily and Sunday Telegraph; Shiraz Maher, author of Salafi-Jihadism:The History of an Idea; and Azadeh Moaveni, author of Lipstick Jihad and Honeymoon in Tehran – I was part of this panel discussing Daesh, Nusra, Assad, Saudi-Iran, and the West. (It was also the first time I saw a finished copy of our book Burning Country).

From Deep State to Islamic State

An edited version of this piece was published at Newsweek Middle East edition.

An edited version of this piece was published at Newsweek Middle East edition.

In 2011, according to the ASDA’A Burson-Marsteller Arab Youth Survey, “living in a democracy” was the most important desire for 92% of respondents. A mere four years later, however, 39% of Arab youths believed democracy would never work in the Arab world, and perceived ISIS, not dictatorship, as their most pressing problem.

Powerful states seem to share the perception, bombing ISIS as a short-term gestural response to terrorism, re-embracing ‘security states’ in the name of realism – concentrating on symptoms rather than causes.

How did the bright revolutionary discourse of 2011 turn so fast to a fearful whisper? Jean-Pierre Filiu’s “From Deep State to Islamic State” – a passionate, sometimes polemical, and very timely book – examines “the repressive dynamics designed to crush any hope of democratic change, through the association of any revolutionary experience with the worst collective nightmare.”

For historical analogy, Filiu evokes the Mamluks, Egypt’s pre-Ottoman ruling caste. Descended from slaves, these warriors lived in their own fortified enclaves, and considered the lands and people under their control as personal property. Filiu sees a modern parallel in the neo-colonial elites – militarised elements of the lower and rural classes – who hijacked independence in Algeria, Egypt, and Syria (and, in different ways, in Libya, Iraq, Tunisia and Yemen).

The Syrian Jihad

This was published at the National.

This was published at the National.

Security discourse dominates the international chatter on Syria. Most Syrians see Assad as their chief enemy – he is after all responsible for the overwhelming proportion of dead and displaced. But the Syrian people are not invited to the tables of powerful states, who are in agreement that their most pressing Syrian enemy is ‘terrorism’.

There is disagreement on who exactly the terrorists are. Vladimir Putin shares Assad’s evaluation that everyone in armed opposition is an extremist, and at least 80% of Russian bombs have therefore struck the communities opposing both Assad and ISIS. North of Aleppo, Russia has even struck the rebels while they were batttling ISIS. This wave of the ‘War on Terror’ – now led, with plenty of historical irony, by Russia and Iran – uses anti-terror rhetoric to engineer colonial solutions, just as the last wave did, and ends up promoting terror like never before.

There is no question that the moderate Syrian opposition exists, in the form of hundreds of civilian councils, sometimes directly elected, and at least 70,000 democratic-nationalist fighters. In a recent blog for the Spectator, Charles Lister, one of the very few Syria commentators to deserve the label ‘expert’, explains exactly who they are.

Lister’s book-length study “The Syrian Jihad”, on the other hand, focuses on those militias, from the Syrian Salafist to the transnational Jihadist, which cannot be considered moderate. It clarifies the factors behind the extremists’ rise to such strategic prominence, amongst them the West’s failure to properly engage with the defectors and armed civilians of the Free Syrian Army (FSA) in 2011 and 2012.

The Sound and The Fury

This was first published (with some great links) at the Guardian. Picture is Abu Hajar. More stories about him and many others in our forthcoming book ‘Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War’.

This was first published (with some great links) at the Guardian. Picture is Abu Hajar. More stories about him and many others in our forthcoming book ‘Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War’.

In the first heady weeks of the Arab Spring commentators made much of the role played by social media, and certainly Facebook in particular provided an indispensable tool to young revolutionaries throughout the region. But less noticed, and ultimately far more significant, was the carnivalesque explosion of popular culture in revolutionary public spaces.

The protests in Syria against Bashaar al-Assad’s dictatorship were far from grim affairs. Despite the ever-present risk of bullets, Syrians expressed their hopes for dignity and rights through slogans, graffiti, cartoons, dances and songs.

To start with, protestors tried to reach central squares, hoping to emulate the Egyptians who occupied Tahrir Square. Week after week residents of Damascus’s eastern suburbs tried to reach the capital’s Abbasiyeen Square, and were shot down in their dozens. Tens of thousands did manage to occupy the Clock Square in Homs, where they sang and prayed, but in a matter of hours security washed them out with blood.

This April 2011 massacre tolled an early funeral bell for peaceful protest as a realistic strategy. In response to the unbearable repression, the revolution gradually militarised. By the summer of 2012 war was spinning in downward spiral: the regime added sectarian provocation to its ‘scorched earth’ tactics of bombardment and siege; foreign states and transnational jihadists piled in; those refugees who could got out.

Civil revolutionaries did their best to adapt. Alongside self-organising committees and councils, Syrians set up independent news agencies, tens of radio stations and well over 60 newspapers and magazines. Kafranbel, for instance, a rural town become famous for its witty and humane slogans, broadcasts discussion, news and women’s programmes on its own ‘Radio Fresh’ – despite a recent assault by Jabhat al-Nusra fighters. And Enab Baladi (My Country’s Grapes), is a newspaper published by women in Daraya, a besieged, shelled and gassed Damascus suburb. Remarkably, the magazine focuses on unarmed civil resistance.

As a result of both security concerns and communal solidarity, anonymous cooperative endeavours proliferated, amongst them photography collectives such as the Young Syrian Lenses.

The Crossing

This review of Samar Yazbek’s “The Crossing: My Journey to the Shattered Heart of Syria” was first published at the Daily Beast.

This review of Samar Yazbek’s “The Crossing: My Journey to the Shattered Heart of Syria” was first published at the Daily Beast.

This shocking, searing and beautiful book is an account of three visits to Idlib province in northern Syria, an area liberated from the Assad dictatorship “on the ground but betrayed by the sky.”

In the face of regime repression, Syria’s non-violent protests of 2011 had transformed into an armed uprising in 2012. By August of that year, when the author – exiled Syrian novelist and journalist Samar Yazbek – made her first trip, Assad’s forces had been driven from the rural border zones. From a distance, however, via warplanes and long-range artillery, they implemented a policy of scorched earth and collective punishment. So Yazbek finds her homeland changed to a landscape of burnt fields and cratered market places, with boys picking through collapsed homes in search of things to sell and displaced families sheltering in tombs and caves. Death is ever-present. Gardens and courtyards have become cemeteries. Yazbek never shies away from the horror but builds something worthwhile from it, a record and a reflection, for death is ultimately “the impetus of writing and its source.”

Known today only for war, Syria is heir to an ancient civilisation. Idlib province houses the remains of Ebla, a five-thousand-year-old city, and is dotted with half-intact Byzantine towns and churches. The war’s “ruthless sabotage of history” has damaged these priceless sites. In Maarat al-Numan the statue of 9th Century poet Abu Alaa al-Maari, a native of the town highly respected in his own time despite his unusual atheism, has been decapitated by armed Islamists. And the wonderful mosaic museum at the same location has been bombed by the regime and looted by various militias.

But amid these ruins Yazbek encounters a people giving voice to their aspirations after half a century of enforced silence. In revolutionary towns the walls are “turned into open books and transient art exhibits”. Activists organise “graffiti workshops, cultural newspapers, magazines for children, training workshops, privately-run community schools.” In the context of state collapse these projects are born of necessity, but they also reflect the kind of society the revolutionaries hoped to build – inclusive, democratic, forward-looking – one which they are in fact trying to build, even as extremists fashion their own, much darker versions. Through self-organised committees and councils, Yazbek is told, “each region now has its own administration, and every village looks after itself.” This – Syrians’ willed self-determination, Syrian creativity amid destruction – is the positive story so often missed in the news cycle, and it represents a hope for the future, faint though it is. The activists know they are working against insurmountable odds, but continue anyway. They document atrocities and reach out to international media, an endeavour which has so far failed to bear tangible fruit. When they can, they laugh – it’s “as though they inhaled laughter like an antidote to death.”

The Dictator’s Last Night

An edited version of this review appeared in the Guardian.

An edited version of this review appeared in the Guardian.

Colonel Gaddafi – “the Brotherly Guide, the miracle boy who became the infallible visionary” – possessed a character so colourful it begged entry into fiction. Yasmina Khadra – pseudonym for Algerian ex-military man and bestselling writer Mohammed Moulessehoul – obliges here in “The Dictator’s Last Night”, a title to be fitted alongside such great dictator novels as Marquez’s “The Autumn of the Patriarch” or Vargas Llosa’s “The Feast of the Goat” (the latter set in the last hours of the Dominican strongman Trujillo). Although Khadra matches neither the epic scale nor the experimental virtuosity of those two, his writing here is compulsive, funny, powerfully emotional, and often sinuously intelligent.

For his last night, the “untameable jealous tiger that urinates on international conventions to mark his territory” is confined to a disused school in Sirte, the sky aflame with NATO bombs and rebel bullets, his generals either fleeing or collapsing from exhaustion.

Like Hitler in the bunker he rails against his people’s betrayal – “Libya owes me everything!” – against the West which so recently feted him and, with no irony at all, against his fellow Arab autocrats, those “pleasure-seeking gluttons.”

Khadra’s imagining of him is probably pretty accurate: bullying, mercurial, grandiose, containing an egomaniac’s contradictions – self-obsessed but craving approval, ruthless but oversensitive. It’s “my full moon, nobody else’s,” he declares, and “Everything I did worked.”

Gaddafi remembers his poor Beduin beginnings, fatherless and disturbed, and his struggles against “the barriers of prejudice”. He was spurned when, as a young officer, he proposed marriage to a social superior. The reader sympathises with the humiliation – until shown the nature of the dictator’s later response. Gaddafi’s voice careers from sentimentality to brutality and back, and at first the reader’s heart follows.

To read is to switch between extremes, for Gaddafi is “One day the predator, the next the prey,” and because that’s the way his mind works anyway. His massacres and sordid revenge dramas are interweaved with his romanticism, by the poetry of desert life. His belief in himself as “mythology made flesh” alternates with a fatalism in which he merely plays a role written by a forgetful God.

After his nightly heroin injection, Gaddafi remembers “the women I have graced with my manhood”. He evokes the “sublime illness called love” even as he recounts his rapes, his conquests “inert at my feet”. The writer chooses (perhaps judiciously) not to make too much of this aspect of the dictator’s personality. The facts recounted in Annick Cojean’s book “Gaddafi’s Harem” are far more lurid than Khadra is here.

Saud Alsanousi Interview

I interviewed Kuwaiti novelist Saud Alsanousi for the National. My earlier review of his novel “The Bamboo Stalk” is here.

Born in 1981, Kuwaiti writer Saud Alsanousi won the 2013 International Prize for Arabic Fiction (IPAF) for his novel “The Bamboo Stalk”. A warm and generous interlocutor, here he speaks about otherness, his ‘method-writing’ approach to characterisation, and his aversion to the ‘shock method’…

RYK: Why did you choose the half-Kuwaiti, half-Filipino Isa/Josè as your hero?

SA: Since my childhood I’ve been interested in the image of the other. The other was always seen negatively, whether he was a Westerner, an east Asian, or an Arab from beyond the Gulf. And in turn the West, the Asians, and the Arabs saw us as the other. Of course I rejected their negative image. At the same time I realised that some of it was true – we Kuwaitis had social problems, we were closed in upon ourselves, we didn’t know any culture except our own. We always think we’re right and the other is wrong, socially, religiously. Through reading and travel I discovered that the world was much bigger than us, that we weren’t the axis of the whole universe.

How could I approach the topic in writing? I thought a novel would be better than journalism, because a newspaper article is a brief phenomenon, whereas when a reader follows the life story of a character through a novel, day by day and page by page, he builds a relationship with that character, he really engages with him.

And why Josè specifically? Previous stories about ‘the other’ have focused on the West. We already know the West looks down on us, how Hollywood depicts us, and we’re used to it. Instead I wanted to concentrate on those some may consider our inferiors. I chose the lowest class, those who serve us in shops and hospitals. I wanted to imagine how they see us. Of course, the hero had to be half-Kuwaiti in order to gain intimate access to a Kuwaiti household. My first idea was to make him half-Indian, but the problem with that was that he wouldn’t look foreign enough. He could pass easily for a Kuwaiti. But Josè looks east Asian, and is judged by his appearance.

RYK: How did you set about building the character?

SA: I only talk for myself, but I found that research by reading and watching documentaries wasn’t nearly enough. It produced only cold information, and when I wrote the result looked like a tourism brochure.

So I travelled to the Philippines and lived in a simple house in a traditional village. I wore their clothes. I ate their food and I breathed their air. And I met a lot of expatriate workers in Kuwait, not just Filipinos, and listened to their problems.

I embodied the character. I’m not exaggerating when I say that when I came back home, from the moment I arrived in the airport, I wasn’t Saud Alsanousi but Josè Mendoza. I saw my own country through the eyes of a stranger. From May 2011 to May 2012, while I was writing, I continued to be Josè. I visited the places he would, I rode a bike like him, I tuned my satellite to the Filipino channels, even if I didn’t understand the language. And I surrounded my workspace with bamboo. I could only write the character by embodying it.

Instead of Freedom, Annihilation

This piece was published at the Guardian.

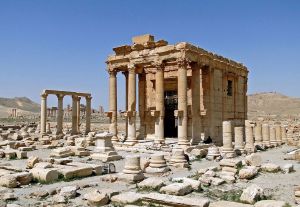

In the last week of its Syrian rampage, ISIS bulldozed the 1500-year-old monastery of Mar Elian in al-Qaryatain and blew up the 2000-year-old temples of Baalshamin and Bel in Palmyra.

Syria’s heritage illustrates civilisational history from the Sumerians to the Ottomans. Its universal significance provoked French archeologist Andre Parrot’s comment, “Every person has two homelands… His own and Syria.” For Syrians themselves, these sites provided a palpable link to the past and, it seemed, to the future too, for they once assumed their distant descendants would also marvel at them. Such monuments were references held in common regardless of sect or politics. Like Stonehenge or Westminster Abbey, they provided a focus for nationalist pride and belonging. Naturally, they would have been central to any future tourism industry. Now they are vanishing.

Very recently the potential future looked very different. The popular revolution of 2011 announced a new age of civic activism and fearless creativity, but the regime’s savage repression led inevitably to the revolution’s militarisation, and then war.

Assad’s scorched earth – artillery barrages, barrel bombs and starvation sieges on residential neighbourhoods – has displaced over half the population. Four million are outside, subsisting in the direst conditions. Traumatisation, the world’s failure to properly arm the Free Army, and the West’s refusal to act when Assad used sarin gas, handed the reins to various Islamists.

Four years in, Syria is prey to division, nihilism, and competing totalitarianisms. A third of the country is split between Kurds, the Free Army and either moderate or extreme Islamic-nationalist groups. The rest is divided between what leftist intellectual Yassin al-Haj Saleh calls ‘bearded’ and ‘necktie’ fascism. Syria’s Sykes-Picot borders were drawn by imperialists to manifest an inherently unjust order; today’s partition scenarios look even worse.

The Dissolution of Past and Present

An edited version of this piece was published at the National.

An edited version of this piece was published at the National.

Zabadani, a mountain town northwest of Damascus near the Lebanese border, was one of the first Syrian towns to be liberated from the Assad regime (in January 2012) and one of the first to establish a revolutionary council. (The martyred anarchist revolutionary Omar Aziz was involved in setting up this council, as well as the council in Barzeh). Zabadani has been besieged and intermittently shelled since its liberation. And since July 3rd this year it has been subjected to a a full-scale assault by (the Iranian-backed) Lebanese Hizbullah, alongside continuous barrel bombing. Apparently the town’s 800-year-old al-Jisr mosque has been pulverised. Human losses are in the hundreds, and beyond the numbers, incalculable.

In other news, Daesh (or ISIS) has bulldozed the 1500-year-old monastery of Mar Elian in al-Qaryatain and blown up the beautiful 2000-year-old temple of Baalshamin in Palmyra. The temple once mixed Roman, Egyptian and Mesopotamian styles. Today its rubble is further evidence that there will be no resumption of Syrian normality. The people, monuments, even landscapes that Syrians once took for granted, that they assumed their grandchildren would enjoy, are disappearing for ever.

Palmyra – Queen Zenobia’s desert city – is a world heritage site and perhaps Syria’s most precious cultural jewel. Remarkably intact until recently, it provided a tangible link to antiquity and a breathtaking proof of the region’s civilisational wealth. Nationalist Syrians, whether secular or Islamist, feel the importance of such sites for communal pride and identity. Rational Syrians can at least understand their utilitarian benefit to any future tourism industry.

Neither Bashaar al-Assad nor (Daesh ‘caliph’) Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi are nationalists. Al-Baghdadi is explicit about it: “Syria is not for the Syrians,” he says, “and Iraq is not for the Iraqis.” Al-Assad’s rhetoric is still nationalist (and sectarian), but his war effort is managed by a foreign power now pushing towards the nation’s partition. Though not nationalists, both are certainly fascists obsessed with reinforcing their respective totalitarian states and eliminating any independent intellectual influence. Thus, in a flesh-and-blood echo of its slaughter of Palmyran history, Daesh tortured and publically beheaded Palmyra’s head of antiquities, 81-year-old Khaled al-Assa‘ad, perhaps because he’d refused to reveal the location of hidden treasures.

Bitter Almonds

An edited version of this review appeared at the National.

An edited version of this review appeared at the National.

This story starts with a birth and a departure, in Jerusalem in 1948. The birth is Omar Bakry’s, and it orphans him. The departure, alongside three quarters of a million others, is his forced expulsion from Palestine. “We’ll be back in a couple of weeks,” one fatefully quips.

Omar, now in the care of a neighbouring family, relocates to Damascus, where the novel unfolds through the fifties and sixties, both an engaging romance and a convincing period drama.

Lilas Taha writes in American English. My British-English ear found it difficult at first to believe in old-fashioned Arabs saving each others’ asses and getting in each others’ faces. The effect was exacerbated by occasionally clumsy dialogue. Real Palestinian-Syrians would see no need to specify, for example, “the ruling Baath Party” or “the actress Souad Hosni”. Realism is lost at moments such as these when the novel, veering into explanatory overstatement, seems too obviously an act of cultural translation. It might have been better to write a preface, or to add footnotes.

But as the pages turn, slowly but surely, the characters come entirely credibly to life. We learn a great deal about them by observing their negotiations of etiquette and social ritual as they traverse a domestic danger zone marked by deaths, difficult births, precarious marriages, and looming scandals.

The cast is close-knit. Mustafa is a farmer denied his land whose lungs are broken in a wool factory. The book’s title comes from his mouth, and provides a wisdom for the drama: “The bitter almonds make you savour the sweet ones more.” His wife Subhia, their son Shareef and daughters Huda and Nadia, make up Omar’s surrogate family.

Taha depicts them trying to make ends meet, their life in cramped quarters, male and female sleeping areas demarcated by a blanket, and the profound familiarities and festering resentments which grow in such conditions.

The Drone Eats With Me

This appeared first at The National.

This appeared first at The National.

Plenty of news flows out from Gaza, but very little human information. This emotional blackout bothered Ra Page, founder of Comma Press, a Manchester-based publisher producing groundbreaking short story collections. It was Comma that gave the astounding Iraqi surrealist writer Hassan Blasim his first break. Comma has published a high-quality series of literary responses to scientific innovations as well as several collections based around cities such as Tokyo, Istanbul and Liverpool. Why not Gaza too?

“My rather naive idea with The Book of Gaza,” writes Page, “was to try to inch the city ever so slightly closer to a state of familiarity, to establish it as a place and not just a name, through the simple details that a city’s literature brings with it – the referencing of street names, the name-dropping of landmarks and districts.”

The book was by no means the first literary project to aim in some way to normalise Palestinian life. Since 2008 the Palestinian Festival of Literature (Palfest), brainchild of novelist Ahdaf Soueif, has tried to reaffirm, in Edward Said’s phrase, “the power of culture over the culture of power”. In practical terms, this means transforming a literature festival into a roadshow – Jerusalem one night, Bethlehem another, Ramallah on a third… Though these places are only a few miles apart, checkpoints prevent Palestinians from travelling between them. So the guest writers travel to their audience, and at the same time learn something of Palestine’s enormous creativity. This stateless nation has boasted many great literary talents, most notably Mahmoud Darwish and Mourid Barghouti in poetry and Ghassan Kanafani in prose. Meanwhile there are burgeoning film and music (especially hip hop) scenes.

For decades writers had to smuggle their manuscripts out of Gaza to presses in Jerusalem, Cairo or Beirut. The shorter the text, the more likely it was to be published. As a result, the Strip became an “exporter of oranges and short stories.” Edited by novelist and journalist Atef Abu Saif, The Book of Gaza contains stories from three generations. It achieves both the sense of place that Page hoped for and ‘familiarity’ through its treatment of universal themes. The stories are as likely to deal with women “besieged by preconceptions” (in Najlaa Ataallah’s words) as the seige imposed by Israel. The project succeeded in ‘depoliticising’ Gaza, at least to some extent.

But then, immediately after publication, Israel launched Operation Protective Edge. Story contributors were directly affected by the assault. Writer Asmaa al-Ghoul, for instance, lost nine members of her extended family. Page was driven to this bleak conclusion: “There is no stability in Gaza on which to build a reader-familiarity.”