The Pen and the Sword

This review was originally published in the indispensable Electronic Intifada.

This review was originally published in the indispensable Electronic Intifada.

Edward Said was one of the great public intellectuals of the twentieth century – prolific, polymathic, principled, and always concerned to link theory to practice. Perhaps by virtue of his Palestinian identity, he was never an ivory tower intellectual. He never feared dirtying his hands in the messy, unwritten history of the present moment. Neither was he ever a committed member of a particular camp. Rather he offered a discomfiting, provocative, constantly critical voice. And against the postmodern grain of contemporary academia, his perspective was consistently moral, consistently worried about justice.

Said was primarily a historian of ideas. More precisely, he was interested in ‘discourse’, the stories a society tells itself and by which it (mis)understands itself and others. His landmark book “Orientalism” examined the Western narrative of empire in the Islamic Middle East, as constructed by Flaubert and Renan, Bernard Lewis and CNN. Said’s multi-disciplinary approach, his treatment of poetry, news coverage and colonial administration documents as aspects of one cultural continuum, was hugely influential in academia, helping to spawn a host of ‘postcolonial’ studies. Said’s “Culture and Imperialism” expanded the focus to include Western depictions of India, Africa, the Caribbean and Latin America, and the literary and political ‘replies’ of the colonised.

To Vote Or Not

Democracy is supposed to mean ‘government by the people’. In the ancient Greek city states all the free men (but not women or slaves) would cram the theatre for lively, informed debate on a relevant issue, and then would decide it by a show of hands. Not so today. Putting a mark on a piece of paper every five years and imagining that you run things seems like a sad parody of such activity, a demotic populism masking power rather than a popular democracy negotiating it.

In our society the most important decisions are often made by unelected movers of capital and unelected civil servants and generals. Elected officials are very often at least as loyal to the lobbies easing their way as to the voters they supposedly represent.

The Screen

There were no classes. Instead we marched down to the square and began to shout slogans. At first the teachers led us but soon we got into a group with no teachers and we could shout what we wanted.

Ya Blair Ya haqeer

dumak min dum al-khanzeer

O Blair, you are mud

Your blood is swine’s blood

It was hard to say the words because I was laughing so loud. Muhannad squashed his nose with his finger and oinked like a pig.

Ya Clinton Rooh Amreeka

Hal mushkiltak ma’ Moneeka

O Clinton Get to America

Solve your problem with Monica

That was the funniest one. Muhannad screamed in my ear about Clinton’s cigar and the Jewish woman, which was bad because a girl was next to me. He told me the story almost every day, but it was funnier this time, or maybe it felt like that because the tall girl was there and such a crowd was in the square. The sky was bright, although it was a cloudy day.

The Madman of Freedom Square

“I see no need to swear an oath in order for you to believe in the strangeness of this world.”

“I see no need to swear an oath in order for you to believe in the strangeness of this world.”

How can imagination respond to a situation like Iraq’s, in which truth is so blatantly stranger and more horrifying than the darkest fiction? Perhaps by simply recording real stories, then sometimes allowing reality to slip a little further in the direction it’s already chosen.

Hassan Blasim, film maker, refugee, and author of the astounding short-story collection “The Madman of Freedom Square,” has a more precise formulation:

“The important thing is to observe at length, like someone contemplating committing suicide from a balcony. The other important thing is to have an imagination which is not melodramatic but malicious and extremely serious, and to have an ascetic spirit that is close to death.”

Except this isn’t a formulation but a voice within a story. In another story there is a man who throws himself from a balcony – a man who clears blood and debris in the aftermath of explosions, then migrates to Holland, renames himself Carlos Fuentes, becomes a Hirsi Ali figure, more Dutch than the Dutch, and suffers nightmares. There’s a man who dreams a number which foretells not a lottery ticket but .. something else. I give away too much.

Blasim slips between first and third person narration, between realism and hyper-realism, fairytale and dream. Better than slip, he weaves, surefooted. The writing is tight, intelligent, urgent. It bears traces of Gogol and Edgar Allen Poe, plus ugly hints of the Brothers Grimm. It’s Gothic but it dispenses with the Gothic mode’s flagged sentiment. Too tough and wise for that.

There is symbolism. There are phantasmagoric tales of people-smuggling, of corpses displayed as public art, of cannibalism. But none of it is fantasy. All of it directly addresses the fate of people tortured by destruction and fire.

Zeitoun

This review was published in the Independent.

Abdulrahman Zeitoun was born in Jebleh, on Syria’s Mediterranean coast. Decades later and thousand of miles away he awakes from dreaming of a fishing expedition out of his childhood home: “Beside him he could hear his wife Kathy breathing, her exhalations not unlike the shushing of water against the hull of a wooden boat.” As so often in Dave Eggers’s latest novel, the docudrama “Zeitoun”, a caught image opens a window on an ocean of memory and a state of mind.

Zeitoun now lives in New Orleans, where he runs a painting and building company and owns several buildings. He’s a dedicated businessman, father, husband, and Muslim. His painter’s van is emblazoned with a rainbow, which Zeitoun soon discovers has gay associations for Americans. But he doesn’t change it. “Anyone who had a problem with rainbows, he said, would surely have trouble with Islam.”

Kathy, practical and strong-willed, was brought up a Baptist in Baton Rouge. Attracted by “the doubt sown into the faith” and “the sense of dignity embodied by the Muslim women she knew,” she converted to Islam after her failed first marriage. Some years later she married the much older Zeitoun. Eggers describes their domestic bustle and warmth, and their personal irritations. For Zeitoun, these include his children’s wastefulness and obsession with pop music, and his alienation in a family of women. Kathy is bothered by Zeitoun’s stubbornness and her own family’s Islamophobic nagging.

Oman Again

To break up the winter I spent most of January visiting my brother-in-law and friends in Oman, where I used to live, and my sisters in Doha, Qatar.

To break up the winter I spent most of January visiting my brother-in-law and friends in Oman, where I used to live, and my sisters in Doha, Qatar.

Since Hamad bin Khalifa Aal Thani deposed his corrupt father, Qatar’s powerful oil and gas economy has expanded and diversified. The state follows an interesting and idiosyncratic foreign policy. It hosts the largest American miltary base in the Gulf, and it also hosts – against American and Arab objections – al-Jazeera. In terms of the regional ‘Resistance Front versus US-client’ dialectic, Qatar stands in the middle, and in 2008 it helped negotiate a Lebanese compromise between the two sides. Wahhabism is influential (my five-year-old niece wants to attend ballet classes, but ballet classes are banned because the costume is considered unIslamic – even for five-year-old girls in a man-free environment), yet women can vote and drive.

Overall, I don’t much like the place. I had a good time with my family, ate some fine meals, went to a book fair. But there’s a bad power game going on in Qatar. Nobody is smiling. I met some very pleasant Qataris – the staff in the excellent Islamic Art Museum, some men in a bowling alley, a retired pearl diver – but I also noticed many refusing to descend from their cars at the grocery shop. (Arabs often expect take-away food to be brought to the car, but not groceries.) Expatriates form a majority of the population. As elsewhere in the Gulf, expatriate wage and class status can be mapped reasonably smoothly onto ethnicity, with white Westerners on top, followed by Lebanese, then other Arabs, then Indonesians, Pakistanis and Indians. Expatriates don’t have citizenship rights, although the infrastructure depends on them. Many contemporary Qataris, in contrast to their proud grandfathers, are obese. The city is one of close walls. The surrounding desert is flat, pale, and begrimed by industry.

The Unnamed

An edited version of this review appeared in the New Statesman.

When death is distant and life is taken for granted our culture forgets God – meaning the God problem – and focuses on bitching instead. This was the focus of Joshua Ferris’s first novel “Then We Came to the End”, an office comedy asking what ultimately is valuable in our bureaucratised existence.

Now Ferris’s eagerly-awaited second novel “The Unnamed” imagines a man forced from a world in which even soap emanates complacency into death’s proximity, where nothing can be taken for granted. God bares his teeth.

Philosopher John Gray describes an experiment which shows, “the electrical impulse that initiates action occurs half a second before we take the conscious decision to act.” The ramifications for our assumptions of agency are unsettling, to say the least. Reading “The Unnamed” is a companion experience.

The Spinning Wheel

This review was written for the Palestine Chronicle.

This review was written for the Palestine Chronicle.

This is not what you expect: an accomplished and self-reflective work of history enclosed within a layer of war reportage – in comic book form. But Joe Sacco’s “Footnotes in Gaza” is just that, an unusually effective treatment of Palestinian history which may appeal to people who would never read a ‘normal book’ on the subject. The writing, however, is at least as good as you’d expect from a high quality prose work. Here, for instance, is page nine: “History can do without its footnotes. Footnotes are inessential at best; at worst they trip up the greater narrative. From time to time, as bolder, more streamlined editions appear, history shakes off some footnotes altogether. And you can see why… History has its hands full. It can’t help producing pages by the hour, by the minute. History chokes on fresh episodes and swallows whatever old ones it can.”

The pictures – aerial shots, action shots, urban still lifes, crafted but realist character studies – work as hard as the words. Sacco depicts fear, humiliation and anger very well indeed, and often achieves far more with one picture than he could in an entire newspaper column. The cranes at work on a Jerusalem skyline are worth a paragraph or two of background. So is the fact that almost every Palestinian male has a cigarette in his mouth. And when dealing with historical process – the changing shape of the camps, for example – the pictures are more than useful.

Defamation and Binary Idiocy

To summarise: I have been smeared by a Scottish newspaper. Most of the words they attribute to me I did indeed say, but they have decontextualised and selected to such an extent that they make me say things I do not believe – for instance that September 11th was a good thing, or that the Taliban should take over Afghanistan. What follows is a rather long description of meeting the man from the gutter press, which I hope will set the record a little straighter. Yesterday, meanwhile, 33 civilians were killed

by NATO bombs in Afghanistan.

I was doorstepped the other morning. A young man wearing a suit and an apologetic manner wanted to ask some questions on behalf of the Scottish Mail on Sunday.

What? Stumbling down the stairs in my thermal underwear, wild-haired and bestubbled, I dream for a passing moment that I’ve become as important to the world as Tiger Woods or Amy Winehouse. Perhaps even now press vermin are going through my rubbish bin. Perhaps paparazzi are crowding the front garden.

Alas, our aspiring hack, young Oliver Tree (for so he called himself), hasn’t yet graduated to the tabloid heights, and neither have I. It soon becomes clear that his mission is much more mundane, is indeed the everyday grind of papers like the Mail: to create outrage where there was none before, to smear, misrepresent and decontextualise, in order to strangle the possibility of real debate.

Myth-Making

We often project our current political concerns backwards in time in order to justify ourselves. I say ‘we’ because everyone does it. Nazi Germany invented a mythical blonde Aryan people who had always been kept down by lesser breeds. The Hindu nationalists in India imagine that Hinduism has always been a centralised doctrine rather than a conglomerate of texts and local traditions, and describe Muslim, Buddhist, Christian, Sikh, Jain and animist influences on Indian history as foreign intrusions. Black nationalists in the Americas depict ancient Africa as a continent not of hunter-gatherers and subsistence farmers but as a wonderland of kings and queens, gold and silk, science and monumental architecture. To our current cost, Zionists and the neo-cons have been able to reactivate old Orientalist myths in the West, myths in which the entirety of Arab and Islamic history has involved the slaughter and oppression of Christians, Jews, Hindus, women, gays, intellectuals .. and so on.

We often project our current political concerns backwards in time in order to justify ourselves. I say ‘we’ because everyone does it. Nazi Germany invented a mythical blonde Aryan people who had always been kept down by lesser breeds. The Hindu nationalists in India imagine that Hinduism has always been a centralised doctrine rather than a conglomerate of texts and local traditions, and describe Muslim, Buddhist, Christian, Sikh, Jain and animist influences on Indian history as foreign intrusions. Black nationalists in the Americas depict ancient Africa as a continent not of hunter-gatherers and subsistence farmers but as a wonderland of kings and queens, gold and silk, science and monumental architecture. To our current cost, Zionists and the neo-cons have been able to reactivate old Orientalist myths in the West, myths in which the entirety of Arab and Islamic history has involved the slaughter and oppression of Christians, Jews, Hindus, women, gays, intellectuals .. and so on.

Such retrospective mythmaking frequently goes to the most absurd extremes in young nations conscious of their weakness or of a need for redefinition (America may be one of these). Probably for that reason it is particularly evident in the Middle East.

Mornings in Jenin

This review was published in today’s Times.

This review was published in today’s Times.

According to the Zionist story, Palestine before the state of Israel was ‘a land without a people awaiting a people without a land.’ Writers from Mark Twain to Leon Uris, as well as Hollywood studios and certain church pulpits, retell the tale. But Palestinians, in the West at least, lack a popular counter-narrative. Palestinians are reported on, met only on the news.

Perhaps this is changing. As the land disappears from under their feet Palestinians have been investing in culture, and an explosion of Palestinian talent is becoming visible in the West, in films, hip-hop, poetry and novels. And now Susan Abulhawa’s “Mornings in Jenin” is the first English language novel to fully express the human dimension of the Palestinian tragedy.

The story begins with the Abulheja family at home in the village of Ein Hod near Haifa, marrying, squabbling, trading, and harvesting the olives. It’s a touching and sometimes funny portrait of rural life with hints of the city (notably the Jerusalem-based Perlsteins, refugees from German anti-Semitism) and the Beduin tribes.

Then comes the Nakba, or Catastrophe, of 1948. Driven from their shelled village, the family suffers loss, separation, and humiliation, ending up in a camp in Jenin where “the refugees rose from their agitation to the realisation that they were slowly being erased from the world.” By now we care very much about the key characters, and through them we experience “that year without end”, the interminably drawn out Nakba which stretches through some of the bloodier signposts of Palestinian history – the Naksa or Disaster of 1967, the Lebanese refugee camp massacres, until the 2002 Jenin massacre.

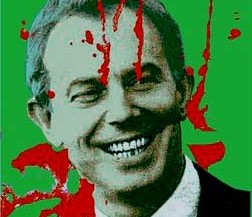

Criminal and Accomplice

I didn’t watch Blair’s performance at the Chilcot inquiry, for health reasons, but I did read that he mentioned Iran 30 times, as in ‘the same good case for war applies to Iran’. This comes in the context of America concentrating ships and missiles in the Gulf. It is unlikely that the US will attack Iran directly, but increasingly likely that Israel will provoke a conflict. Blair may be preparing the ground for this.

I didn’t watch Blair’s performance at the Chilcot inquiry, for health reasons, but I did read that he mentioned Iran 30 times, as in ‘the same good case for war applies to Iran’. This comes in the context of America concentrating ships and missiles in the Gulf. It is unlikely that the US will attack Iran directly, but increasingly likely that Israel will provoke a conflict. Blair may be preparing the ground for this.

Blair felt ‘responsibility but no regret’ over the destruction of Iraq which has killed over a million, created at least four million refugees, and turned a fertile land into a diseased desert. He focused on Saddam Hussain’s monstrosity, but refrained from explaining how Saddam’s most monstrous crimes were supported by his Western backers. He was allowed to refrain. He didn’t entertain the possibility that Hussain could have been deposed in other ways. He blamed Iran and al-Qa’ida, neither of which had a presence in the country before its collapse, for Iraq’s problems, and again his illogic was not questioned.

This Evening

It was a relationship abrasive and intimate, based on love. So a good relationship. To his children he barked commands, swore, adopted strict military monotones, or ignored them, ordered them out. Underneath it was love. Usually his anger was feigned. He didn’t know how else to control his thoughts when children were screaming. He wasn’t a multitasker. So it wasn’t so much a matter of controlling the children as of organising himself, except on certain planned occasions. The children understood this.

It was a relationship abrasive and intimate, based on love. So a good relationship. To his children he barked commands, swore, adopted strict military monotones, or ignored them, ordered them out. Underneath it was love. Usually his anger was feigned. He didn’t know how else to control his thoughts when children were screaming. He wasn’t a multitasker. So it wasn’t so much a matter of controlling the children as of organising himself, except on certain planned occasions. The children understood this.

For a while he lay in the bed with the girl to read her from a book of prehistory. He read a page she read a page. It was volcanoes and evolution versus creation myths. Then he called the boy to come and join them. Come and read the good book, he said. His mother had read him the Bible when he was young although she wasn’t a Christian, or it must have been selections, but he remembered the dark shock of Noah drunk and naked cursing his son to enslavement, and Lot’s daughters spicing their father’s drink just right to get him drunk, but not too drunk to fuck, and Abraham pimping his wife, twice, and God rewarding him for it, and the passion and strangeness of it all. He was grateful to his mother for showing him this stuff and was passing the favour to his own children. Except he sent the girl out of the room for the aforementioned parts. She was only seven after all. Both children enjoyed it, just the Book of Genesis so far.

What Comes Next

This is the extended version of a piece published in today’s Sunday Herald.

A strange calm prevails on the Middle Eastern surface. Occasionally a wave breaks through from beneath – the killing of an Iranian scientist, a bomb targetting Hamas’s representative to Lebanon (which instead kills three Hizbullah men), a failed attack on Israeli diplomats travelling through Jordan – and psychological warfare rages, as usual, between Israel and Hizbullah, but the high drama seems to have shifted for now to the east, to Afghanistan and Pakistan. The Arab world (with the obvious exception of Yemen) appears to be holding its breath, waiting for what comes next.

Iraq’s civil war is over. The Shia majority, after grievous provocation from takfiri terrorists, and after its own leaderhip made grievous mistakes, decisively defeated the Sunni minority. Baghdad is no longer a mixed city but one with a large Shia majority and with no-go zones for all sects. In their defeat, a large section of the Sunni resistance started working for their American enemy. They did so for reasons of self-preservation and in order to remove Wahhabi-nihilists from the fortresses which Sunni mistakes had allowed them to build.

The collapse of the national resistance into sectarian civil war was a tragedy for the region, the Arabs and the entire Muslim world. The fact that it was partly engineered by the occupier does not excuse the Arabs. Imperialists will exploit any weaknesses they find. This is in the natural way of things. It is the task of the imperialised to rectify these weaknesses in order to be victorious.