The Palestinisation of the Syrian People

Sarajevo, Bosnia

A slightly edited version of this article was published at al-Jazeera.

In solidarity with Aleppo, the lights on the Eiffel Tower were extinguished. Elsewhere in Paris, and in London, Amsterdam, Oslo and Copenhagen, people demonstrated against the slaughter. Turks rallied outside Russian and Iranian embassies and consulates in Istanbul, Ankara and Erzerum. The people of Sarajevo – who have their own experience of genocide – staged a big protest.

The protests are nothing like as large as they were when the United States bombed Iraq, but they are welcome nonetheless. If this level of support had been apparent over the last six years, it would have made a real difference. Perhaps it is making a difference even now. Public sympathy for the victims may have pressured Vladimir Putin to allow those in the surviving liberated sliver of Aleppo to evacuate rather than face annihilation. At the time of writing, the fate of the deal is in doubt, subject to the whims of the militias on the ground. If it works out and the tens of thousands currently trapped are allowed to leave – the best possible outcome – then we will be witnesses to an internationally brokered forced population transfer. This is both a war crime and a crime against humanity, and a terrible image of the precarious state of the global system. The weight of this event, and its future ramifications, deserve more than just a few demonstrations.

The abandonment of Aleppo is a microcosm of the more general abandonment of Syria’s

Casablanca, Morocco

democratic revolution. It exposes the failures of the Arab and Muslim worlds, of the West, and of humanity as a whole.

Many Syrians expected the global left would be first to support their cause, but most leftist commentators and publications retreated into conspiracy theories, Islamophobia, and inaccurate geo-political analysis, and swallowed gobbets of Assadist propaganda whole. Soon they were repeating the ‘war on terror’ tropes of the right.

The Obama administration provided a little rhetorical support, and sometimes allowed its allies to send weapons to the Free Army. Crucially, however, Obama vetoed supply of the anti-aircraft weapons the Free Army so desperately needed to counter Assad’s scorched earth. In August 2013, when Assad killed 1500 people with sarin gas in the Damascus suburbs, Obama’s chemical ‘red line’ vanished, and the US more or less publically handed Syria over to Russia and Iran.

Revolutionary Women

This is the third text I wrote for the Making Light exhibition in Exeter. The first is here, and the second here.

This is the third text I wrote for the Making Light exhibition in Exeter. The first is here, and the second here.

A young woman ties a keffiyeh around her face. The text reads: “I’m coming out to protest.”

From a hole in another girl’s head, butterflies rush out. A girl shot in the head, like so many girls, but the butterflies suggest she’s achieved a kind of freedom – either the freedom that motivated the defiant act that provoked her murder, or simply the freedom of death. The text reads: “Your bullets have only killed the fear within us.”

Women have been at the forefront of Syria’s revolutionary struggle.

Women have been at the forefront of Syria’s revolutionary struggle.

The two most important grassroots revolutionary coalitions were set up by women: the General Commission of the Syrian Revolution by Suhair Atassi, and the Local Coordination Committees by Razan Zeitouneh.

Suhair Atassi went on to play important roles in the Syrian National Council and the Coalition of Revolutionary and Opposition Forces.

As well as setting up the LCCs, Razan Zeitouneh, a human rights lawyer, helped establish the Violations Documentation Centre to record and publicise the regime’s killings and detentions. After some time living underground, she moved to Douma, a liberated town near Damascus, where she was forthright in her criticism of any authoritarian actor who sought to limit the people’s freedom, whether the regime or any of the militias which had been formed to fight the regime.

In December 2013 Razan was abducted, probably by Jaish al-Islam, an Islamist militia. Three others were taken with her: the activists Samira al-Khalil, Wael Hamada, and Nazem Hammadi. Collectively they are known as the Douma Four. Nothing has been heard of them since.

Before her abduction, Samira Khalil, a former political prisoner, was setting up micro-finance projects and women’s centres in the Douma area. Similar centres operate all over those parts of Syria liberated from both Assad and ISIS.

Victory is Guaranteed

This old man has habitually kind eyes

but now he’s in a rage

arms flap cheeks bunch hands wave

If you burn the earth under us

we will not leave

If you kill us all

we will not leave

If you bury us

we will not leave

The victory of a man on the floor of a cell

or hung from the ceiling

who does not count

who no longer feels the blows

The victory of a woman

who knows her rapist’s honour is wrecked

of a child

who draws a picture of a different city

Read the rest of this entry »

Addressing the Oireachtas (Me and Hassoun)

Hassoun and Assad

I was happy to have a chance to adress the Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs and Trade in the Irish Parliament. I spoke about the crushing of the Syrian revolution and the Russian and Iranian occupation of Syria. You can read my address below.

Before me, the committee was addressed by a delegation of the Syrian regime, headed by the state Mufti, Ahmad Badreddine Hassoun. Hassoun has previously threatened Europe and America with an army of suicide bombers, and has specifically called for the civilians of liberated Aleppo to be bombed. It’s incredible that such a man can get a visa to a European country (unlike millions of desperate Syrians who are not terrorists), let alone address a parliament. Hassoun was also invited to Trinity College, and (most ironic of all) to sign some declaration ‘against extremism’.

Some argue that Hassoun should be heard in the interests of balance and free speech. I say that all Syrian perspectives should be heard, and that I would have no problem with a delegation of pro-Assad civilians making their case. My problem is with this official regime propaganda exercise, at a time when the regime and its backers are slaughtering and expelling civilians en masse. And of course the people who talk about balance and free speech in this case don’t apply the principle in all cases. I don’t see official representatives of ISIS being invited to make their case in these settings. And ISIS, monstrous as it is, has killed, raped, and tortured far, far fewer people than the Assad regime.

Thanks to the work of the wonderful people in the Irish Syria Solidarity Movement, the Irish people were alerted to Hassoun’s nature. This report was on the RTE news. In the Arab media, Asharq Al-Awsat, al-Quds al-Arabi and the New Arab have also covered Hassoun’s visit.

Here is the filmed record of the sessions, first Hassoun’s group, then me. And here is my address:

It Will Not Happen Again

This is the second text I wrote for the Making Light exhibition in Exeter (the first is here).

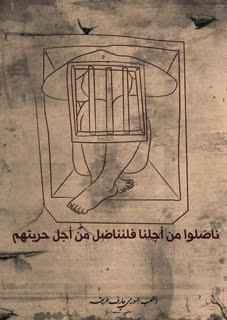

Two posters juxtaposed.

Two posters juxtaposed.

A man impossibly crammed in a cage. “They struggled for our freedom,” reads the text, “so let’s struggle for theirs.”

Beside a noria, one of the ancient water-wheels of the ancient city of Hama, a child writes on a wall: “It will not happen again.” The phrase combines bitter irony and fierce defiance, for even as we read it we know that it has happened again, it is happening, and ten or a hundred times worse.

In 1982 there was a massacre in Hama. Its memory haunted and silenced Syrians until 2011. The massacre was a success for the regime, and therefore a model for its current policy.

An anti-regime movement began to organise in 1978. It wasn’t a mass movement of the scale and breadth of the 2011 revoution, but it included leftists, nationalists and democrats as well as Islamists. The regime responded with a dual policy of extreme repression and radicalisation of their opponents, murdering, torturing and imprisoning them en masse. By 1982 not much was left of the movement other than the radicalised armed wing of the Muslim Brotherhood which, mixing stupidity with desperation, took over Hama by force of arms.

An anti-regime movement began to organise in 1978. It wasn’t a mass movement of the scale and breadth of the 2011 revoution, but it included leftists, nationalists and democrats as well as Islamists. The regime responded with a dual policy of extreme repression and radicalisation of their opponents, murdering, torturing and imprisoning them en masse. By 1982 not much was left of the movement other than the radicalised armed wing of the Muslim Brotherhood which, mixing stupidity with desperation, took over Hama by force of arms.

The regime welcomed the confrontation as an opportunity to teach the country an unforgettable lesson. Making no distinction between civilians and insurgents, its army levelled the city’s historical districts with tank, artillery and aerial bombardment. With churches, mosques and markets burning, its soldiers went house to house, riddling whole families with bullets. Estimates of the dead range from ten to forty thousand. Many thousands more were killed elsewhere in the country.

Thousands of political prisoners were thrown into the country’s dungeons. Hundreds were hanged, shot, or otherwise murdered inside. The rest languished for decades without sufficient food, medical care, any comfort or hope. Their relatives feared to ask after them.

Salafi-Jihadism and Interpretive Gymnastics

This review of Shiraz Maher’s book was first published at the National.

This review of Shiraz Maher’s book was first published at the National.

Currently under military pressure in Iraq and Syria, and still terrorising civilians far beyond those lands, ISIS has horrified and bewildered Muslims and non-Muslims alike. Its carefully studied barbarism and cinematic savagery seem to owe as much to Hollywood action movies and computer combat games as to classical Islamic jurisprudence. The furiously destructive passions of its adherents often appear insane.

ISIS is certainly immoral, but not entirely irrational. Its actions are rooted in specific political contexts and based on a greatly contested analysis of ancient and contemporary Islamic texts. Shiraz Maher’s magisterial “Salafi-Jihadism: The History of an Idea” provides an “explanatory backstory” to this and other manifestations of what could be called in shorthand the al-Qaida tradition.

Salafists preach “progression through regression”, specifically a return to the practice of the first three generations of Muslims known as the salaf al-salih, or the ‘righteous predecessors’.

Although its antecedents go back at least to the medieval theologian Ibn Taymiyya, Salafism is a modern phenomenon – a traumatised response to modernity – developed in the last 150 years. There are ‘quietist’ and ‘activist’ strains, but Maher’s book focuses on the ‘violent-rejectionists’ who have risen to prominence even more recently. Their ascent since the early 1990s coincided with a decline in those varieties of political Islam which hoped to achieve power through reformist or democratic means. By this period, the Syrian and Egyptian wings of the Muslim Brotherhood had been crushed, Tunisia’s Ennahda movement suffered a harsh crackdown, the leaders of Saudi Arabia’s Sahwa movement were imprisoned, and elections won by Islamists in Algeria were cancelled.

Maher quotes Trotsky’s dictum that “War is the locomotive of history”. The war sparked by the suspension of Algerian democracy, the anti-Soviet war in Afghanistan, the wars in Iraq, and today’s conflict in Syria, constitute stations in the development of Salafi-Jihadism, a movement which is at once revolutionary and deeply reactionary.

Civil Disobedience

Anyone near Exeter should make sure to visit Making Light’s exhibition Stories from Syria (and visit the website). I wrote three small texts to accompany some of the art work. Here’s the first:

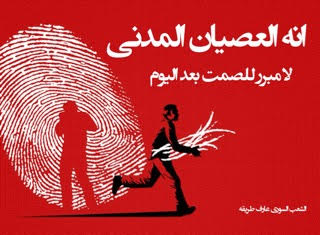

Two posters made in early 2011.

Two posters made in early 2011.

One reads: “It’s civil disobedience. No excuse for silence after today.”

A figure grabs lines from a thumb print, and runs. The thumb print evokes ID cards and the whole machinery of state. The figure is fleeing surveillance, therefore, and defining his own identity as he does so. Have those lines transformed into sticks in his arms? Is he about to light a fire?

The figure in the second poster is trapped inside a ‘no entry’ road sign, either dismantling it, and by implication the political prohibitions in Syrian society, or saying ‘no’ himself, refusing orders.

The words in this one read: “Civil disobedience. I don’t obey the law of an illegitimate  authority.” The sentence is a response to a regime poster campaign of the period. One of those official slogans read: “I obey the law.”

authority.” The sentence is a response to a regime poster campaign of the period. One of those official slogans read: “I obey the law.”

The revolutionary poster aims to force a dialogue where before there was only monologue. It answers back.

Before 2011, nobody answered back, at least not in public. Back then, veteran dissident (and long-term political prisoner) Riad al-Turk was entirely just when he called Syria a “kingdom of silence”.

Syrians were terrified to speak openly and honestly about domestic politics. Those who did either had to leave the country or were imprisoned for decades in the most brutal conditions. The state had ears and eyes everywhere, spies in every workplace, school and café. It owned all the tongues in the country, every newspaper, every radio and TV station. It decided which books were published and which films were shot. It dominated trades unions and universities and every last inch of the public space, even the graffiti on the walls.

In 2000, Bashaar al-Assad inherited power from his father Hafez. The new president’s neo-liberal (and crony-capitalist) economic reforms impoverished the countryside and city suburbs while excessively enriching a tiny elite. Rami Makhlouf, for instance, the president’s tycoon cousin, was estimated to control 60% of the national economy by 2011.

In the spring of 2011, Syrians refound their voices. Enmired in increasing poverty, rejecting the humiliations of unending dictatorship, lashing out against corruption, and encouraged by the Arab Spring uprisings nearby, they took to the streets.

What’s at Stake in Aleppo?

Leila and I spoke at SOAS in London on the revolution in Aleppo, the committees and councils there, the women’s centres, free newspapers and education projects, the military leaders, as well as the Russian and Iranian occupations and their crimes.

It certainly isn’t the most coherent or time-organised talk we’ve done, but the event went very well (a great, engaged, diverse audience). You can listen to it here.

Anarchism

I came across anarchism too late in life to start calling myself an anarchist. At earlier stages I’d enjoyed attaching labels to myself, like ‘leftist’, or ‘Arab’, or ‘Muslim’. I was never a great believer in any of them, but I tried.

When the Arab revolutions made politics real for me, I became suspicious of adopting any labels, given as they referred to me, and politics wasn’t about me any more, not about my fantasies of myself, my need to see myself as on the right side, or my ‘identity’. When the revolutions broke out, and then the counter-revolutions and wars, I understood that real politics concerns the actual struggles of real people in the real world. (I also understood that all identity politics is ultimately a distraction, and one most often used by those in power – or those who aim to achieve power – to divide and rule their subjects). I became suspicious of all grand narratives and all ideological frameworks which assumed there was a perfect solution to human problems as well as a clear path towards it.

So I’m not going to call myself an anarchist. And even if I wanted to, I probably couldn’t, because I am ultimately undecided on the question of whether people could do better without states and hierarchical authority. I’d like to believe that we could run complex modern societies on a horizontal basis more successfully than we do at present, but then I don’t know if I have that much faith in humanity. Perhaps we do need hierarchy of some sort to organise ourselves and to control our anti-social urges, and the best we can hope to do is reform and restrain the hierarchy. I don’t know. I need to read much more and think much more – and even when I do, if I decide I know for sure one way or the other, please ask me to check my arrogance. I’m not capable of knowing. None of us are.

I’ve written a book about Syria with someone who describes herself as an anarchist, and I agree with her on nearly everything. Plus I’ve found anarchists much less likely than leftists to be snagged by allegiance to some state or other. Their conversation on Syria is therefore likely to be much more interesting. At those book events we’ve done which were liberally salted by anarchists, in Seattle, for instance, or Toronto, the discussion was intelligent, nuanced, informed. Compassionate too. I admired the anarchists I met in Spain for several reasons. Most of them at least.

But then Noam Chomsky has been described as an anarchist. Here’s where I get confused, because Chomsky doesn’t usually (or ever?) adhere to what I think are anarchist principles.

Guapa

This review was first published, slightly edited, at the Guardian.

This review was first published, slightly edited, at the Guardian.

“There is everything that ever happened, and then there is this morning.”

Rasa’s grandmother – Teta – has discovered him in bed with his boyfriend Taymour. It’s a potential disaster for Taymour, who tries to “play by the rules, one foot in and one foot out”, and for Rasa it precipitates a crisis of eib, or shame, the fear of what people will say and the necessity of lying it imposes.

Since boyhood he has obsessed with finding a word to define him: louti – sodomite, or khawal – effeminate, or gay, first heard on TV when George Michael came out, or even shaath – “queer, deviant, abject”.

But Teta’s spying and screaming is only one of Rasa’s problems.

His friend Maj has been arrested. Rasa isn’t sure if it’s because of his human rights work or on account of his sexuality. In a hidden nightclub called Guapa – the “pocket of hope” which gives Saleem Haddad’s wonderful debut its title – Maj often belly dances in full niqab and a print of Marilyn Monroe’s face. He calls this “war-on-terror neo-Orientalist gender-fucking”. “We are all performing,” Maj declares, referring back to eib, and to the demands of survival in a prying dictatorship.

The president’s gaze, no less than Teta’s, “unpacks your existence bit by bit until you are naked and helpless, your most secret thoughts out in the open for all to see.”

Rasa lives in a unnamed, composite Arab city clogged with traffic, policemen, cynical cab drivers, and new and old waves of refugees. People clutch cigarettes and Turkish coffee in their well-chewed fingers. The air smells of jasmine. The walls are adorned with posters of the president in various costumes.

‘Criminals Kill While Idiots Talk’

The Pluto blog has published an extract from our book. Here it is:

The Pluto blog has published an extract from our book. Here it is:

‘Burning Country’, written by Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila Al-Shami, explores the horrific and complicated reality of life in present-day Syria with unprecedented detail and sophistication, drawing on new first-hand testimonies from opposition fighters, exiles lost in an archipelago of refugee camps, and courageous human rights activists among many others. These stories are expertly interwoven with a trenchant analysis of the brutalisation of the conflict and the militarisation of the uprising, of the rise of the Islamists and sectarian warfare, and the role of governments in Syria and elsewhere in exacerbating those violent processes. In this extract taken from the book, Robin Yassin – Kassab and Leila Al-Shami dissect the 2014 seizure of Mosul and impact it had in Iraq and Syria and on international opinion.

In June 2014, ISIS led an offensive which took huge swathes of northern and western Iraq out of government hands. Most significantly, the city of Mosul, Iraq’s second largest, fell to ISIS on 10 June  after only four days of battle. General Mahdi al-Gharawi – a proven torturer who had run secret prisons but was nevertheless appointed by Prime Minister Maliki as governor of Nineveh province – fled, and his troops, who greatly outnumbered the ISIS attackers, deserted. This meant that the US-allied Iraqi army, on which the US had spent billions of dollars, was less able to take on ISIS than Syria’s ‘farmers and dentists’. Many Syrians saw a conspiracy in the Iraqi collapse, a play by Malki to win still more weapons from America, and by Iran to increase its regional importance as a counterbalance to Sunni jihadism. It’s more likely that the fall of Mosul was an inevitable result of the Iraqi state’s sectarian dysfunction. Shia soldiers felt themselves to be in foreign territory, and weren’t prepared to die in other people’s disputes. Many Sunni soldiers defected to ISIS.

after only four days of battle. General Mahdi al-Gharawi – a proven torturer who had run secret prisons but was nevertheless appointed by Prime Minister Maliki as governor of Nineveh province – fled, and his troops, who greatly outnumbered the ISIS attackers, deserted. This meant that the US-allied Iraqi army, on which the US had spent billions of dollars, was less able to take on ISIS than Syria’s ‘farmers and dentists’. Many Syrians saw a conspiracy in the Iraqi collapse, a play by Malki to win still more weapons from America, and by Iran to increase its regional importance as a counterbalance to Sunni jihadism. It’s more likely that the fall of Mosul was an inevitable result of the Iraqi state’s sectarian dysfunction. Shia soldiers felt themselves to be in foreign territory, and weren’t prepared to die in other people’s disputes. Many Sunni soldiers defected to ISIS.

ISIS’s control of the Iraq–Syria border, and especially of Mosul, was a game changer. The organisation collected the arms left behind by the Iraqi army, much of it high-quality weaponry inherited from the American occupation. Perhaps more importantly, it cleaned out Mosul’s banks. Then it returned to Syria in force, using the new weapons to beat back the starved FSA and the new money to buy loyalties.

The FSA and Islamic Front in Deir al-Zor, besieged by both Assad and ISIS for months, begged the United States for ammunition, warning the city was about to fall. Their plea was ignored, and the revolutionary forces (plus Jabhat al-Nusra) pulled out in July, leaving the province’s oil fields, and the Iraqi border area, in ISIS’s hands. ISIS reinforced itself in Raqqa and surged back into the Aleppo countryside and the central desert. Suddenly it dominated a third of Iraq and a third of Syria. In a tragic parody of the old Arab nationalist dream, it made good propaganda of erasing the Sykes–Picot border; in a tragic parody of Islamic history, it declared itself a Caliphate at the end of June.

Norway

Mazen Darwish

It was a pleasure to visit Oslo, where my co-author Leila al-Shami and I were hosted by the Literaturhuset and the Syrian Peace Action Centre. Of course, not every moment was pleasurable. A couple of audience comments reminded us of the rising red-brown tide of counter-revolutionary propaganda spouted by people who describe themselves as ‘leftists’ as well as those honest enough to identify openly with the far right. Sam Hamad calls this ‘the fascism of the 21st Century‘. Karam Nachar (a member of the Local Coordination Committees and editor of al-Jumhuriya) gave a fascinating talk on the intersection of political and cultural activism in Syria. Afterwards a Nordic fascist stood up and said, “You claim President Assad is killing people, but is it surprising when the rebels are being armed by colonial powers?” Such a statement not only ignores (and justifies) the Russian and Iranian imperialist assault on Syria, but also encapsualtes the stunning (willed) ignorance of those who believe that the United States is trying to get rid of the Assad regime. After another talk, a Norwegian said he’d recently visited Damascus, “where everything was fine”, and explained how Assad is defending Christians. Anyone in central Damascus in possession of eyes and ears can hear the bombs falling and see the smoke rising from the suburbs. Fortunately the exemplary revolutionary (and great writer) Marcell Shehwaro, who happens to be a Christian, was there to put him in his place.

It’s distressing enough that the violence wielded against east Aleppo and other liberated areas of Syria has reached truly genocidal levels. In addition we are forced to observe the ugly spectacle of so-called ‘experts’, ‘leftists’ and ‘journalists’ cheerleading the slaughter. (One such is the grotesque far-rightist-posing-as-progressive Jill Stein.) In such a grim context, it was balm for the brain to spend time with Syrian (and Lebanese and Palestinian) revolutionaries in Oslo. Perhaps the greatest honour was meeting Mazen Darwish of the Syrian Centre for Media and Freedom of Expression, a man of great principle and intelligence, who has paid a great price.

If you follow this link, you’ll see Mazen and I speaking about Aleppo on Norwegian TV.

No Knives in the Kitchens of this City

This review of the latest novel by Khaled Khalifa – an examination of Aleppo’s decades-long strangulation at the hands of the Assad regime – was published at the Guardian.

This review of the latest novel by Khaled Khalifa – an examination of Aleppo’s decades-long strangulation at the hands of the Assad regime – was published at the Guardian.

Were Syrians wise to revolt? Aren’t they worse off now?

Such questions misapprehend the situation. Syrians didn’t decide out of the blue to destroy a properly functioning state. The state had been destroying them, and itself, for decades. “No Knives in the Kitchens of this City”, the new novel by Khaled Khalifa, chronicles this long political, social and cultural collapse, the incubator of contemporary demons.

The story stretches back to World War One and forward to the American occupation of Iraq, but our narrator’s “ill-omened birth” coincides with the 1963 Baathist coup. The regime starts off as it means to continue. The maternity hospital is looted and emptied of patients. Soon the schools and universities are purged. Only pistol-toting loyalist professors survive. Public and individual horizons shrink as the president’s powers grow beyond all limits, through Emergency Law, exceptional courts, and three-hour news broadcasts covering “sacred directives made to governors and ministers”.

The novel follows a large and well-drawn cast – a family, their friends, enemies and lovers – back and forward across three generations. This multiple focus and enormous scope turns the setting – the city of Aleppo – into the novel’s central ‘character’. “Cities die just like people,” Khalifa writes. So ancient neighbourhoods are demolished, and lettuce fields give way to spreading slums.

“No Knives in the Kitchens of this City” won the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature. As in many of Mahfouz’s novels, Khalifa’s urban environment develops a power somewhere between metaphor and symbol: “The alley was witness to the destruction of my mother’s dreams, and the idea of this alley grew to encompass the length and breadth of the country.”

A Social Media Mea Culpa

Jill Stein in Moscow

On Facebook (which steals my time and makes me angrier than I already am) I remarked that the Tories will be in power for another decade in Britain now that ‘leftists’, mistaking an electoral party for a social movement, have re-elected the pro-Putin, pro-Khamenei Jeremy Corbyn to leadership of the Labour Party. (Here is the excellent Sam Hamad on Corbyn’s foreign policy.) Likewise, or even worse, some American ‘leftists’ will be voting for Jill Stein in their presidential elections. Stein believes that wi-fi rays (not just internet use) damage our brains. She attended a dinner with Putin in Moscow, then told Russia Today that ‘human rights discourse resonates here’. This while Russia occupies parts of Ukraine and rains white phosphorus and thermite cluster bombs on Syrian hospitals. Speaking in a city where it isn’t safe to be black, or openly gay, to write investigative journalism, or to dissent from the Putin line. Stein’s running mate believes that Assad won an election fair and square. Even if she could win, this hippy-fascist mix would not in any way be a progressive alternative. But of course she can’t win. What she can do is take votes from Hillary Clinton, and help Trump to win (something Putin is praying for). Yes, Clinton is as horrible as anyone from the American establishment, but she’s a hell of a lot better than Trump, the white-nationalist candidate whose election will have immediate and terrible effects on American society. As Clay Claiborne points out, voting for Stein in this context may be one definition of white privilege.

The discussion after my anti-Corbyn post includes me commenting on the stuff I wrote on this blog before 2011 (particularly on Iran), and one lesson I think I’ve learned since. As that stuff can still be viewed here, I’m posting part of the discussion.

subMedia and others

I am interviewed (from 14 minutes to the end) in Requiem for Syria, a generally excellent and very sweary film by subMedia, an anarchist news channel in Canada. It’s particularly good to see their nuanced take on the (Kurdish) Democratic Union Party, or PYD. You can watch the episode here.

Henry Peck interviewed Leila al-Shami and me for Guernica magazine. You can read that here.

And Ursula Lindsey reviewed our book ‘Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War’, alongside other books, for the Nation. That’s here.