Archive for the ‘Syria’ Category

Victory is Guaranteed

This old man has habitually kind eyes

but now he’s in a rage

arms flap cheeks bunch hands wave

If you burn the earth under us

we will not leave

If you kill us all

we will not leave

If you bury us

we will not leave

The victory of a man on the floor of a cell

or hung from the ceiling

who does not count

who no longer feels the blows

The victory of a woman

who knows her rapist’s honour is wrecked

of a child

who draws a picture of a different city

Read the rest of this entry »

Addressing the Oireachtas (Me and Hassoun)

Hassoun and Assad

I was happy to have a chance to adress the Joint Committee on Foreign Affairs and Trade in the Irish Parliament. I spoke about the crushing of the Syrian revolution and the Russian and Iranian occupation of Syria. You can read my address below.

Before me, the committee was addressed by a delegation of the Syrian regime, headed by the state Mufti, Ahmad Badreddine Hassoun. Hassoun has previously threatened Europe and America with an army of suicide bombers, and has specifically called for the civilians of liberated Aleppo to be bombed. It’s incredible that such a man can get a visa to a European country (unlike millions of desperate Syrians who are not terrorists), let alone address a parliament. Hassoun was also invited to Trinity College, and (most ironic of all) to sign some declaration ‘against extremism’.

Some argue that Hassoun should be heard in the interests of balance and free speech. I say that all Syrian perspectives should be heard, and that I would have no problem with a delegation of pro-Assad civilians making their case. My problem is with this official regime propaganda exercise, at a time when the regime and its backers are slaughtering and expelling civilians en masse. And of course the people who talk about balance and free speech in this case don’t apply the principle in all cases. I don’t see official representatives of ISIS being invited to make their case in these settings. And ISIS, monstrous as it is, has killed, raped, and tortured far, far fewer people than the Assad regime.

Thanks to the work of the wonderful people in the Irish Syria Solidarity Movement, the Irish people were alerted to Hassoun’s nature. This report was on the RTE news. In the Arab media, Asharq Al-Awsat, al-Quds al-Arabi and the New Arab have also covered Hassoun’s visit.

Here is the filmed record of the sessions, first Hassoun’s group, then me. And here is my address:

It Will Not Happen Again

This is the second text I wrote for the Making Light exhibition in Exeter (the first is here).

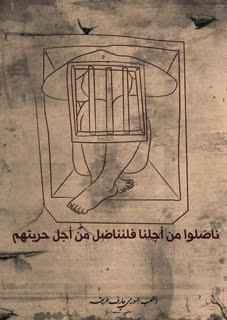

Two posters juxtaposed.

Two posters juxtaposed.

A man impossibly crammed in a cage. “They struggled for our freedom,” reads the text, “so let’s struggle for theirs.”

Beside a noria, one of the ancient water-wheels of the ancient city of Hama, a child writes on a wall: “It will not happen again.” The phrase combines bitter irony and fierce defiance, for even as we read it we know that it has happened again, it is happening, and ten or a hundred times worse.

In 1982 there was a massacre in Hama. Its memory haunted and silenced Syrians until 2011. The massacre was a success for the regime, and therefore a model for its current policy.

An anti-regime movement began to organise in 1978. It wasn’t a mass movement of the scale and breadth of the 2011 revoution, but it included leftists, nationalists and democrats as well as Islamists. The regime responded with a dual policy of extreme repression and radicalisation of their opponents, murdering, torturing and imprisoning them en masse. By 1982 not much was left of the movement other than the radicalised armed wing of the Muslim Brotherhood which, mixing stupidity with desperation, took over Hama by force of arms.

An anti-regime movement began to organise in 1978. It wasn’t a mass movement of the scale and breadth of the 2011 revoution, but it included leftists, nationalists and democrats as well as Islamists. The regime responded with a dual policy of extreme repression and radicalisation of their opponents, murdering, torturing and imprisoning them en masse. By 1982 not much was left of the movement other than the radicalised armed wing of the Muslim Brotherhood which, mixing stupidity with desperation, took over Hama by force of arms.

The regime welcomed the confrontation as an opportunity to teach the country an unforgettable lesson. Making no distinction between civilians and insurgents, its army levelled the city’s historical districts with tank, artillery and aerial bombardment. With churches, mosques and markets burning, its soldiers went house to house, riddling whole families with bullets. Estimates of the dead range from ten to forty thousand. Many thousands more were killed elsewhere in the country.

Thousands of political prisoners were thrown into the country’s dungeons. Hundreds were hanged, shot, or otherwise murdered inside. The rest languished for decades without sufficient food, medical care, any comfort or hope. Their relatives feared to ask after them.

Civil Disobedience

Anyone near Exeter should make sure to visit Making Light’s exhibition Stories from Syria (and visit the website). I wrote three small texts to accompany some of the art work. Here’s the first:

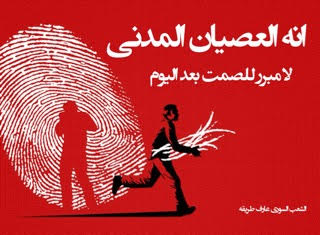

Two posters made in early 2011.

Two posters made in early 2011.

One reads: “It’s civil disobedience. No excuse for silence after today.”

A figure grabs lines from a thumb print, and runs. The thumb print evokes ID cards and the whole machinery of state. The figure is fleeing surveillance, therefore, and defining his own identity as he does so. Have those lines transformed into sticks in his arms? Is he about to light a fire?

The figure in the second poster is trapped inside a ‘no entry’ road sign, either dismantling it, and by implication the political prohibitions in Syrian society, or saying ‘no’ himself, refusing orders.

The words in this one read: “Civil disobedience. I don’t obey the law of an illegitimate  authority.” The sentence is a response to a regime poster campaign of the period. One of those official slogans read: “I obey the law.”

authority.” The sentence is a response to a regime poster campaign of the period. One of those official slogans read: “I obey the law.”

The revolutionary poster aims to force a dialogue where before there was only monologue. It answers back.

Before 2011, nobody answered back, at least not in public. Back then, veteran dissident (and long-term political prisoner) Riad al-Turk was entirely just when he called Syria a “kingdom of silence”.

Syrians were terrified to speak openly and honestly about domestic politics. Those who did either had to leave the country or were imprisoned for decades in the most brutal conditions. The state had ears and eyes everywhere, spies in every workplace, school and café. It owned all the tongues in the country, every newspaper, every radio and TV station. It decided which books were published and which films were shot. It dominated trades unions and universities and every last inch of the public space, even the graffiti on the walls.

In 2000, Bashaar al-Assad inherited power from his father Hafez. The new president’s neo-liberal (and crony-capitalist) economic reforms impoverished the countryside and city suburbs while excessively enriching a tiny elite. Rami Makhlouf, for instance, the president’s tycoon cousin, was estimated to control 60% of the national economy by 2011.

In the spring of 2011, Syrians refound their voices. Enmired in increasing poverty, rejecting the humiliations of unending dictatorship, lashing out against corruption, and encouraged by the Arab Spring uprisings nearby, they took to the streets.

What’s at Stake in Aleppo?

Leila and I spoke at SOAS in London on the revolution in Aleppo, the committees and councils there, the women’s centres, free newspapers and education projects, the military leaders, as well as the Russian and Iranian occupations and their crimes.

It certainly isn’t the most coherent or time-organised talk we’ve done, but the event went very well (a great, engaged, diverse audience). You can listen to it here.

‘Criminals Kill While Idiots Talk’

The Pluto blog has published an extract from our book. Here it is:

The Pluto blog has published an extract from our book. Here it is:

‘Burning Country’, written by Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila Al-Shami, explores the horrific and complicated reality of life in present-day Syria with unprecedented detail and sophistication, drawing on new first-hand testimonies from opposition fighters, exiles lost in an archipelago of refugee camps, and courageous human rights activists among many others. These stories are expertly interwoven with a trenchant analysis of the brutalisation of the conflict and the militarisation of the uprising, of the rise of the Islamists and sectarian warfare, and the role of governments in Syria and elsewhere in exacerbating those violent processes. In this extract taken from the book, Robin Yassin – Kassab and Leila Al-Shami dissect the 2014 seizure of Mosul and impact it had in Iraq and Syria and on international opinion.

In June 2014, ISIS led an offensive which took huge swathes of northern and western Iraq out of government hands. Most significantly, the city of Mosul, Iraq’s second largest, fell to ISIS on 10 June  after only four days of battle. General Mahdi al-Gharawi – a proven torturer who had run secret prisons but was nevertheless appointed by Prime Minister Maliki as governor of Nineveh province – fled, and his troops, who greatly outnumbered the ISIS attackers, deserted. This meant that the US-allied Iraqi army, on which the US had spent billions of dollars, was less able to take on ISIS than Syria’s ‘farmers and dentists’. Many Syrians saw a conspiracy in the Iraqi collapse, a play by Malki to win still more weapons from America, and by Iran to increase its regional importance as a counterbalance to Sunni jihadism. It’s more likely that the fall of Mosul was an inevitable result of the Iraqi state’s sectarian dysfunction. Shia soldiers felt themselves to be in foreign territory, and weren’t prepared to die in other people’s disputes. Many Sunni soldiers defected to ISIS.

after only four days of battle. General Mahdi al-Gharawi – a proven torturer who had run secret prisons but was nevertheless appointed by Prime Minister Maliki as governor of Nineveh province – fled, and his troops, who greatly outnumbered the ISIS attackers, deserted. This meant that the US-allied Iraqi army, on which the US had spent billions of dollars, was less able to take on ISIS than Syria’s ‘farmers and dentists’. Many Syrians saw a conspiracy in the Iraqi collapse, a play by Malki to win still more weapons from America, and by Iran to increase its regional importance as a counterbalance to Sunni jihadism. It’s more likely that the fall of Mosul was an inevitable result of the Iraqi state’s sectarian dysfunction. Shia soldiers felt themselves to be in foreign territory, and weren’t prepared to die in other people’s disputes. Many Sunni soldiers defected to ISIS.

ISIS’s control of the Iraq–Syria border, and especially of Mosul, was a game changer. The organisation collected the arms left behind by the Iraqi army, much of it high-quality weaponry inherited from the American occupation. Perhaps more importantly, it cleaned out Mosul’s banks. Then it returned to Syria in force, using the new weapons to beat back the starved FSA and the new money to buy loyalties.

The FSA and Islamic Front in Deir al-Zor, besieged by both Assad and ISIS for months, begged the United States for ammunition, warning the city was about to fall. Their plea was ignored, and the revolutionary forces (plus Jabhat al-Nusra) pulled out in July, leaving the province’s oil fields, and the Iraqi border area, in ISIS’s hands. ISIS reinforced itself in Raqqa and surged back into the Aleppo countryside and the central desert. Suddenly it dominated a third of Iraq and a third of Syria. In a tragic parody of the old Arab nationalist dream, it made good propaganda of erasing the Sykes–Picot border; in a tragic parody of Islamic history, it declared itself a Caliphate at the end of June.

Norway

Mazen Darwish

It was a pleasure to visit Oslo, where my co-author Leila al-Shami and I were hosted by the Literaturhuset and the Syrian Peace Action Centre. Of course, not every moment was pleasurable. A couple of audience comments reminded us of the rising red-brown tide of counter-revolutionary propaganda spouted by people who describe themselves as ‘leftists’ as well as those honest enough to identify openly with the far right. Sam Hamad calls this ‘the fascism of the 21st Century‘. Karam Nachar (a member of the Local Coordination Committees and editor of al-Jumhuriya) gave a fascinating talk on the intersection of political and cultural activism in Syria. Afterwards a Nordic fascist stood up and said, “You claim President Assad is killing people, but is it surprising when the rebels are being armed by colonial powers?” Such a statement not only ignores (and justifies) the Russian and Iranian imperialist assault on Syria, but also encapsualtes the stunning (willed) ignorance of those who believe that the United States is trying to get rid of the Assad regime. After another talk, a Norwegian said he’d recently visited Damascus, “where everything was fine”, and explained how Assad is defending Christians. Anyone in central Damascus in possession of eyes and ears can hear the bombs falling and see the smoke rising from the suburbs. Fortunately the exemplary revolutionary (and great writer) Marcell Shehwaro, who happens to be a Christian, was there to put him in his place.

It’s distressing enough that the violence wielded against east Aleppo and other liberated areas of Syria has reached truly genocidal levels. In addition we are forced to observe the ugly spectacle of so-called ‘experts’, ‘leftists’ and ‘journalists’ cheerleading the slaughter. (One such is the grotesque far-rightist-posing-as-progressive Jill Stein.) In such a grim context, it was balm for the brain to spend time with Syrian (and Lebanese and Palestinian) revolutionaries in Oslo. Perhaps the greatest honour was meeting Mazen Darwish of the Syrian Centre for Media and Freedom of Expression, a man of great principle and intelligence, who has paid a great price.

If you follow this link, you’ll see Mazen and I speaking about Aleppo on Norwegian TV.

No Knives in the Kitchens of this City

This review of the latest novel by Khaled Khalifa – an examination of Aleppo’s decades-long strangulation at the hands of the Assad regime – was published at the Guardian.

This review of the latest novel by Khaled Khalifa – an examination of Aleppo’s decades-long strangulation at the hands of the Assad regime – was published at the Guardian.

Were Syrians wise to revolt? Aren’t they worse off now?

Such questions misapprehend the situation. Syrians didn’t decide out of the blue to destroy a properly functioning state. The state had been destroying them, and itself, for decades. “No Knives in the Kitchens of this City”, the new novel by Khaled Khalifa, chronicles this long political, social and cultural collapse, the incubator of contemporary demons.

The story stretches back to World War One and forward to the American occupation of Iraq, but our narrator’s “ill-omened birth” coincides with the 1963 Baathist coup. The regime starts off as it means to continue. The maternity hospital is looted and emptied of patients. Soon the schools and universities are purged. Only pistol-toting loyalist professors survive. Public and individual horizons shrink as the president’s powers grow beyond all limits, through Emergency Law, exceptional courts, and three-hour news broadcasts covering “sacred directives made to governors and ministers”.

The novel follows a large and well-drawn cast – a family, their friends, enemies and lovers – back and forward across three generations. This multiple focus and enormous scope turns the setting – the city of Aleppo – into the novel’s central ‘character’. “Cities die just like people,” Khalifa writes. So ancient neighbourhoods are demolished, and lettuce fields give way to spreading slums.

“No Knives in the Kitchens of this City” won the Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Literature. As in many of Mahfouz’s novels, Khalifa’s urban environment develops a power somewhere between metaphor and symbol: “The alley was witness to the destruction of my mother’s dreams, and the idea of this alley grew to encompass the length and breadth of the country.”

subMedia and others

I am interviewed (from 14 minutes to the end) in Requiem for Syria, a generally excellent and very sweary film by subMedia, an anarchist news channel in Canada. It’s particularly good to see their nuanced take on the (Kurdish) Democratic Union Party, or PYD. You can watch the episode here.

Henry Peck interviewed Leila al-Shami and me for Guernica magazine. You can read that here.

And Ursula Lindsey reviewed our book ‘Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War’, alongside other books, for the Nation. That’s here.

The Prison

This article about Arab prison writing was published at the National.

This article about Arab prison writing was published at the National.

From ‘Prisoner Cell Block H’ to ‘Orange is the New Black’, prison dramas fill the Anglo-Saxon screen. In the Arab world, you’re more likely to see them on the news. In recent months, for example, detainees of the Syrian regime have staged an uprising in Hama prison and been assaulted in Suwayda prison.

No surprise then that contemporary Arab writing features prisons so prominently, sometimes as setting, more often as powerful metaphor.

“About My Mother”, the latest novel by esteemed Moroccan writer Taher Ben Jelloun (who writes in French), is an affectionate but unromantic portrait of his parent trapped by incoherence. The old lady suffers dementia, mistaking times, places and people, but there is a freedom in her long monologues, the flow of memory and shifting scenes, torrents of speech which eventually infect the narration.

The novel is family memoir and social history as well as an experiment with form. Jelloun’s mother was married thrice, and widowed first at sixteen. At the first wedding, the attendants presenting the bride chorus: “See the hostage. See the hostage.”

Fettered by tradition and domestic labour, now by illness and age, she responds with superstition, fatalism and resignation. Her own confinement is echoed by memories of national oppression, first by the French, then by homegrown authorities. She learns to mistrust the police even before her son Taher’s student years are interrupted by eighteen months in army disciplinary camp, punishment for his low-level political activism. “That’s what a police state is,” the adult writes, “arbitrary punishment, cruelty and barbarity.”

Rising Up with Sonali

It was a pleasure to be hosted on ‘Rising Up with Sonali’, an LA-based radio and TV show run by women. We discussed the High Negotiations Committee’s transition plan for Syria, the origins of the Assad dictatorship, and how the revolution erupted.

You can watch or just listen to it here.

Another War Opens

Jerablus residents returning home

This was first published at the New Arab.

On August 9th, Turkish President Erdogan visited Russian President Putin in Saint Petersburg. The two leaders cleared the air after a period of mutual hostility during which Turkey had shot down a Russian fighter jet and Russia had bombed Turkish aid convoys heading to Syria.

Clearly some kind of deal was struck at the meeting. Turkey now feels able to engage in robust interventions in northern Syria against both ISIS and the Democratic Union Party, or PYD, a Kurdish party-militia closely linked to the PKK, a group at war with the Turkish state. Except for the public recognition that Moscow is more relevant than Washington, it isn’t clear what Turkey has given Russia in return. Turkey has after all just supported the rebel push to break the siege of Aleppo.

Perhaps the earliest sign of the new reality was the Assad regime’s aerial bombardment of PYD-controlled territory in Hasakeh. The PYD closed Aleppo’s Castello road to regime traffic in response.

A ceasefire was quickly agreed, but the clash was still a surprising turnaround. Assad had never bombed the PYD before. In fact the two had sometimes collaborated, not as a result of ideological proximity or fraternal feeling, but out of a ruthless pragmatism. The regime withdrew from Kurdish-majority areas without a fight in June 2012. The PYD inherited the security installations in these three cantons – now called Rojava, or western Kurdistan – and Assadist forces were freed up to fight the revolution elsewhere.

On KPFA in Berkeley

Here’s an interview Leila and I did in Berkeley, California in April (or was it early May?) We talked about local democracy and self-organisation in Syria, the fascist and imperialist forces ranged against the revolution, and the idiotic misconceptions of the dominant Western ‘left’.

You can listen to it here.

The Tragedy of Daraya

This was published at The New Arab.

Daraya is – or used to be – a sizeable town in the Damascus countryside. A working and middle-class suburb of the capital, it was also an agricultural centre, famed in particular for its delicious grapes. In recent years the town has become a symbol of the Syrian revolution, and of revolutionary resilience in the most terrible conditions. And now, after its August 25th surrender to the Assad regime, it becomes symbolic of an even larger disaster.

Daraya’s courageous social and political activism stretches back long before the eruption of the revolution in 2011. Its residents protested against Israeli oppression in Palestine during the second intifada, and then against the American invasion of Iraq. Those who believe that Assad’s regime represents popular anti-Zionism and anti-imperialism won’t realise how brave these actions were. Independent demonstrations were completely illegal in Syria, punishable by torture and imprisonment, even if the protests were directed against the state’s supposed enemies. And Daraya’s activism focused on domestic issues too, in the form of local anti-corruption and neighbourhood beautification campaigns.

This legacy of civic engagement owes a great deal to the Daraya-based religious scholar Abd al-Akram al-Saqqa, who introduced his students to the work of ‘liberal Islamist’ and apostle of non-violence Jawdat Said, and was twice arrested as a result. Jawdat Said emphasised, amongst other things, rights for women, the importance of pluralism, and the need to defend minority groups.

In 2011 Daraya became one of the most important laboratories for exploring the possibilities of non-violent resistance. Ghiath Matar, known as ‘little Gandhi’, put al-Saqqa and Said’s principles into practice by encouraging protestors to present flowers and bottles of water to the soldiers bussed in to shoot them. The regime responded, as usual, with staggering violence. Matar, a 26-year-old tailor, was arrested in September 2011. Four days later his mutilated corpse was returned to his parents and pregnant wife.

From the start, despite the regime’s divide-and-rule provocations, Daraya’s protest movement rejected sectarian polarisation. As in Deraa and Homs, Christians in the town joined protests, and church bells rang in revolutionary solidarity with the martyrs. Even as Salafism and jihadism rose to prominence elsewhere in the traumatised country, Daraya preserved its tolerance.

The Battle for Aleppo

A slightly edited version of this article was published at the New Arab.

Aleppo is 7000 years old, its mythical origins mixed up with the prophet Abraham and a milk cow, its opulent history underwritten by its place on the Silk Road. Socially and architecturally unique, in its pre-war state Muslims and Christians, and Arabs, Armenians, Turkmen and Kurds, lived and traded in streets redolent sometimes of the Ottoman empire, sometimes of corners of Paris. Before the war Aleppo contained the world’s largest and most intact Arab-Islamic Old City. Now – with the covered souq, the Umayyad mosque, and many other markets, baths and caravansarays destroyed – that honour passes to Morocco’s Fes.

Aleppo is 7000 years old, its mythical origins mixed up with the prophet Abraham and a milk cow, its opulent history underwritten by its place on the Silk Road. Socially and architecturally unique, in its pre-war state Muslims and Christians, and Arabs, Armenians, Turkmen and Kurds, lived and traded in streets redolent sometimes of the Ottoman empire, sometimes of corners of Paris. Before the war Aleppo contained the world’s largest and most intact Arab-Islamic Old City. Now – with the covered souq, the Umayyad mosque, and many other markets, baths and caravansarays destroyed – that honour passes to Morocco’s Fes.

The city’s working class eastern districts have been liberated twice in the last five years. On the first occasion, July 2012, armed farmers swept in from the countryside to join urban revolutionaries against their Assadist tormentors and for a few weeks it felt the Assad regime would crumble in Syria’s largest city and economic powerhouse. But the battle soon succumbed to the war’s general logic: rebel ammunition ran out, the fighters squabbled and looted, foreign jihadists took advantage as the stalemate extended.

These strangers pranced about on blast-traumatised horses, imposed their brutal versions of sharia law, murdered a fifteen-year-old coffee-seller for supposed blasphemy, and finally declared themselves a state.

In January 2014, prompted by popular anger, the entire armed rebellion declared war on ISIS, driving it out of western Syria, Aleppo city included. This was the second liberation.

Aleppo is Syria’s most important centre of civil activism. It houses revolutionary councils and emergency healthcare projects, independent newspapers and radio stations, theatre groups and basement schools. Despite the years of barrel bombs and scud missiles, 300,000 people remain in the liberated zone.