Archive for the ‘Iraq’ Category

The Power Shifts Changing the Middle East

I was pleased to be invited again to speak with Faisal al-Yafai on The Lede podcast, connected to the excellent New Lines Magazine. We spoke about Ahmad al-Sharaa’s visits to both Moscow and Washington DC, the role of ideology in today’s Middle East, and even Scottish independence! Raya Jalabi of the Financial Times tals first about the Iraqi militias and the regional changes since & October 2023.

Unhomely Homes: Hassan Blasim’s Sololand

This review was first published at the New Arab.

The narrator of one of the stories in Hassan Blasim’s “Sololand” dreams that he’s written a story in colloquial Iraqi Arabic rather than in standard fusha. He begins reading it to a “hall full of writers, critics and poets … all smoking and glaring at each other.” As soon as he finishes the first line, which repeats a vulgar but realistic Iraqi proverb, “the first shoe hit me from the front row, and then more shoes came thick and fast like a swarm of locusts.”

This reminds me of my own experience attending a literary festival in Erbil, Iraqi Kurdistan, back in 2011. I didn’t commit the sin of reading out a story written in aamiya, but I did make the comparable faux pas of praising Hassan Blasim’s writing to a hall full of Iraqi literary figures. I repeated what I’d written in the Guardian, that Blasim was perhaps the best writer of Arabic fiction alive. This didn’t provoke actual shoes, but it did result in fuming outrage and several angry ripostes. Blasim uses bad language, they said. He is vulgar. He concentrates on topics that are unsuitable for literature.

O but that’s what used to be said about James Joyce, another iconoclast at work in a period of social and cultural turmoil. Those working to find new ways of expressing new realities will inevitably offend sensibilities and step on people’s toes, especially in a country with as many taboos as Iraq.

Iraq is the country that Blasim escaped. His own toes were trodden on in the process. Some of his fingers, to be precise, were cut off during the journey, which took him over the mountains into Iran, then through Turkey and various European countries, working unregistered jobs in dangerous conditions to pay his way. Echoes of the journey can be heard in “The Truck to Berlin”, a horror story from his first collection, “The Madman of Freedom Square” (2009).

That was the collection which elicited my praise, and which I often still give as a present. If the question is: How to write about war, when war provides truths every day that are so much stranger and more macabre than fiction? Then this book answers the question with an inimitable blend of surrealism, cynicism and black humour. (Ahmad al-Saadawi’s very up-to-date fable “Frankenstein in Baghdad” offers another very different answer, and the late Syrian novelist Khaled Khalifa, in “Death is Hard Work”, by far his most pared-down novel, offers yet another.)

“Sololand”, Blasim’s latest collection, is a further high achievement. Two of the three stories offer visions of the kind of social breakdown that forces Iraqis to flee their country, and sandwiched between them another story offers a similarly dark picture of the situations in which they arrive in their supposed lands of refuge.

Read the rest of this entry »The Tragic Arc of Baathism

An edited version of this essay was published by Unherd.

As well as the most persistent, the Syrian Revolution has been the most total of revolutions. Starting in early 2011 and culminating unexpectedly in December of 2024, it – or rather, the Syrian people – managed to oust not only Bashar al-Assad, but also his army, police and security services, his prisons and surveillance system, and his allied warlords, as well as the imperialist states which had kept him in place. The revolutionary victory marked the end of a dictatorship which had lasted 54 years (under Bashar and his father, Hafez), and also the final, belated death of the 77-year-old Baath Party, once the largest institution in both Syria and Iraq.

Founded in Damascus in April 1947, the Arab Socialist Baath Party went through three major stages, each closely related to the vexed political history of the Arab region. The first stage was one of abstract and unrealistic ideals. Baathism was the most enthusiastic iteration of Arab nationalism. Whereas Egyptian president Gamal Abdul Nasser understood the Arab world as a strategic depth for Egypt and a field in which he could exert his own influence, the Baathists had an almost mystical apprehension of the Arabs as a nation transcending historical forces, one which had a “natural right to live in a single state.”

The founding figures were Syrians who had immersed themselves in European philosophy (Bergson, Nietzsche and Marx) while studying at the Sorbonne in Paris. Two of the three founders were members of minority communities, and it’s useful to think of Baathism as a means of constructing an alternative identity to Islam. While Salah al-Din Bitar was a Sunni Muslim, Michel Aflaq was an Orthodox Christian and Zaki Arsuzi was an Alawi who later adopted atheism. The three mixed enlightenment modernism with romantic nationalism. Arsuzi, for instance, believed Arabic, unlike other languages, to be “intuitive” and “natural”. And Aflaq turned the usual understanding of history on its head. He considered Islam to be a manifestation of “Arab genius”, and deemed the ancient pre-Islamic civilizations of the fertile crescent – the Assyrians, Phoenicians, and so on – to be Arab too, though they hadn’t spoken Arabic.

Like other grand political narratives of the 20th Century, Baathism was an attempt to repurpose religious energies for secular ends. The word Baath means “resurrection”. The party slogan was umma arabiya wahida zat risala khalida, or “One Arab Nation Bearing an Eternal Message”, which sounds strangely grandiose even before the realization that umma is the word formerly used to describe the global Islamic community, and that risala is used to refer to the message delivered by the Prophet Muhammad.

The party’s motto – “Unity, Freedom, Socialism” – referred to the desire for a single, unified Arab state from the Atlantic Ocean in the west to the Arabian Gulf in the east, and from Syria in the north to Sudan in the south. The Arab state should be free of foreign control, and should construct a socialist economic system.

This dream was spread by countryside doctors and itinerant intellectuals. In those early days, the leadership consisted disproportionately of schoolteachers and the membership of schoolboys. In 1953, however, the party merged with Akram Hawrani’s peasant-based Arab Socialist Party. This brought it a mass membership for the first time, and it came second in Syria’s 1954 election.

By then, episodes of democracy were becoming more and more rare. Since Colonel Husni al-Zaim’s March 1949 coup – the first in Syria and anywhere in the Arab world – politics was increasingly being determined by men in uniform. The most significant of these soldiers was Nasser, who seized power in Cairo in 1952, then became a pan-Arab hero when he confronted the UK, France and Israel over the Suez canal in 1956.

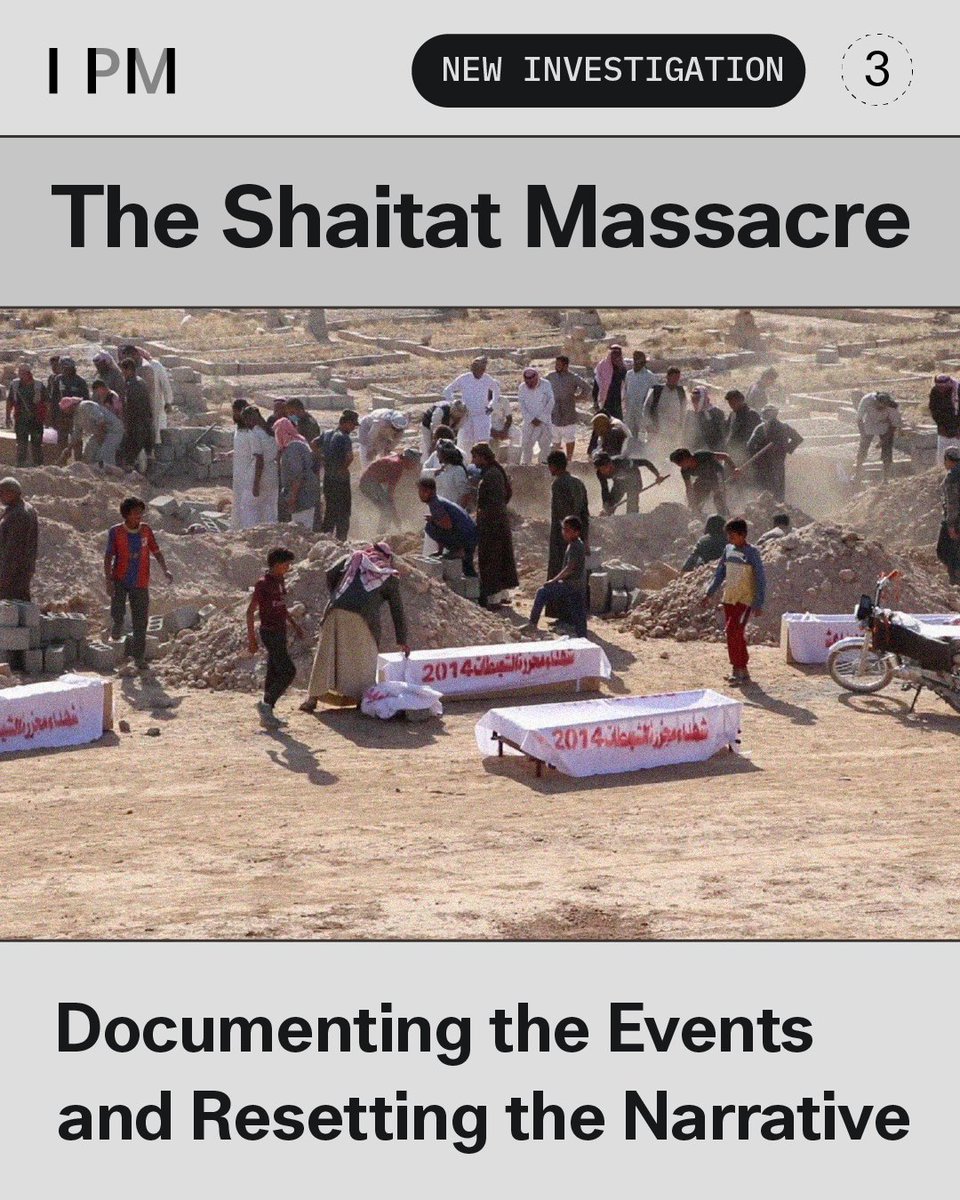

Read the rest of this entry »A Background of Blood

The ISIS Prisons Museum has produced the most comprehensive study yet of the 2014 Shaitat Massacre, the worst ISIS atrocity in Syria. The focus on the massacre includes witness testimonies, 3D prison tours, investigations into some of the dozens of prisons established in the Shaitat areas, and a detailed report on the killing and mass displacement of the clan and the looting and destruction of its property. The report is by far the most serious treatment yet of the events. It’s written by Sasha and Ayman al-Alo, and can be read here.

ISIS violence didn’t drop from the skies. It emerged from a context of massacres in Syria and Iraq perpetrated by the Assad regime, the Saddam Hussein regime, and various actors in the Iraqi and Syrian civil wars, including US troops and sectarian Shia militias. I have written a text to give this context. It’s called A Background of Blood, and can be read here.

The ISIS Prisons Museum on MEMO

I was interviewed at length on the Middle East Monitor podcast about the ISIS Prisons Museum. I’m really pleased to work with this highly-professional, grassroots Syrian and Iraqi project, which brings together human rights, investigative journalism and cutting-edge technology. I gave the interview before the fall of the Assad regime, so I need to update my words by saying that the IPM is currently hard at work documenting the Assad prisons which have just been liberated. It is also publishing reports on Assad security prisons, and witness accounts of detention under Assad. The IPM will continue to display investigations and reconstructions of ISIS crimes alongside work on Assad prisons.

Lesson from Iraq and Syria

Everybody’s asking what lessons can be learned from Iraq twenty years after the invasion and occupation. But more can be learned by looking back further, to 1991.

I’ve just listened to the two episodes on the The Rest is Politics podcast in which Rory Stewart grills Alastair Campbell on the 2003 invasion. It’s a fascinating discussion which I recommend listening to, but there are some glaring omissions. First, there’s lots of talk about British military casualties and the effects on western politics in the years since (and good they mention the Iraq hangover’s role in the west’s criminal inaction in Syria), but not much talk on the hundreds of thousands of dead Iraqi civilians. Next, and most importantly, there is no mention of the American decision in 1991, after driving Iraqi forces from Kuwait, to not only leave Saddam in office but to give him permission to use helicopter gunships to put down the uprising in the mainly Shia Iraqi south.

That was the time to remove Saddam from power, not as a remotely decided regime change, but in support of a population that was already rising against the tyrant. At that key moment, America (and its allies) decided to NOT protect the Iraqi population. America had soldiers right there in southern Iraq watching as Saddam’s forces massacred civilians and filled mass graves. The reason for this was probably fear that Iran would take advantage – but if this terrified decision makers then into such immoral behaviour, why in 2003 did British and American decision makers not bother even considering how Iran would take advantage of their invasion? Of course the end result of the 2003 invasion was the takeover of Iraqi institutions by Iranian-run militias. This was the key factor in the rise of ISIS and then the consequent war to destroy the so-called ‘caliphate’.

So in 1991, after destroying the Iraqi army and liberating Kuwait, the US chose to allow Saddam to slaughter the southern Shia. Then it imposed ruinous sanctions which destroyed the Iraqi middle class. Sectarianism became much worse as Saddam used loyal Sunni troops to massacre Shia, and as he turned to sectarian rhetoric to shore up his damaged rule. By 2003, when the US and Britain decided to invade for their own reasons, on their own timetable, it wasn’t surprising that the place soon collapsed in civil war.

Read the rest of this entry »Iran’s Recipe for Terror Wrapped in War on Terror Packaging

The New Arab published a piece by Iran’s foreign minister. This, my response to Zarif, was also published by the New Arab.

Iraqi Shia militiamen pray in defeated and depopulated Daraya.

Today the New Arab publishes Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif’s latest appeal for greater regional cooperation, specifically to build a collective “security net” which would establish “prosperity, peace, and security for our children.”

This certainly sounds wonderful. Most people in our region share these noble aims. But when they are expressed by an Iranian minister (or by any servant of any state), we owe it to ourselves (and indeed to our children, whose future appears thoroughly insecure) to separate misleading rhetoric from actual facts on the ground. Surely Zarif wouldn’t disagree with this. His own article emphasises the need for “a sound understanding of the current reality.”

Let’s examine the context of this Iranian overture. It doesn’t contain any concessionary policy shift, and is therefore an appeal to the Arab public rather than to state leaderships. Zarif wishes to recreate the pre-2011 atmosphere, those halcyon days when Iran enjoyed enormous soft power across the Arab world. Back then (Iranian president) Ahmadinejad, (Hizbullah chief) Nasrallah and even Bashaar al-Assad topped Arab polls for ‘most admired leader’. Iran was widely considered a proud, rapidly developing Muslim nation and a principled opponent of American and Israeli expansion. Its popularity peaked during the 2006 Israeli-Hizbullah confrontation. People appreciated its aid to the Lebanese militia fighting what they thought was a common cause. When hundreds of thousands of Lebanese Shia fled Israeli bombs for Syria, Syrian Sunnis put any sectarian prejudice aside and welcomed them in their homes. Al-Qusayr, for instance, a town near Homs, welcomed several thousand.

How things have changed. Today many Arabs fear Iran’s expansion just as much as Israel’s. Iran’s rulers, meanwhile, openly boast their imperialism. Here for example is Ali Reza Zakani, an MP close to Supreme Leader Khamenei: “Three Arab capitals have today ended up in the hands of Iran and belong to the Islamic Iranian Revolution.” He referred to Baghdad, Beirut and Damascus, and went on to add that Sanaa would soon follow.

Frankenstein in Baghdad

This review was first published at the New Statesman.

Baghdad, 2005. Occupied Iraq is hurtling into civil war. Gunmen clutch rifles “like farmers with spades” and cars explode seemingly at random. Realism may not be able to do justice to such horror, but this darkly delightful novel by Ahmed Saadawi – by combining humour and a traumatised version of magical realism – certainly begins to.

Baghdad, 2005. Occupied Iraq is hurtling into civil war. Gunmen clutch rifles “like farmers with spades” and cars explode seemingly at random. Realism may not be able to do justice to such horror, but this darkly delightful novel by Ahmed Saadawi – by combining humour and a traumatised version of magical realism – certainly begins to.

After his best friend is rent to pieces by a bomb, Hadi, a junk dealer, alcoholic and habitual liar, starts collecting body parts from explosion sites. Next he stitches them together into a composite corpse. Hadi intends to take the resulting “Whatsitsname” to the forensics department – “I made it complete,” he says, “so it wouldn’t be treated as trash” – but, following a storm and a further series of explosions, the creature stands up and runs out into the night.

At the moment of the Whatsitsname’s birth, Hasib, a hotel security guard, is separated from his body by a Sudanese suicide bomber. The elderly Elishva, meanwhile, is importuning a talking portrait of St. George to return her son Daniel, who – though he was lost at war two decades ago – she is convinced is still alive.

In what ensues, some will find their wishes fulfilled. Many will not. After all, the Whatsitsname’s very limbs and organs are crying for revenge. And as each bodily member is satisfied, it drops off, leaving the monster in need of new parts. Vengeance, moreover, is a complex business. Soon it becomes difficult to discern the victims from the criminals.

‘Sectarianization’

The remains of the Nuri mosque amidst the remains of the ancient city of Mosul, Iraq. photo by Felipe Dana/ AP

An edited version of this article was published in Newsweek.

In his January 20 Inaugural Address, President Trump promised to “unite the civilised world against radical Islamic terrorism which we will eradicate completely from the face of the earth.”

To be fair, he’s only had six months, but already the project is proving a little more complicated than hoped. First, ISIS has been putting up a surprisingly hard fight against its myriad enemies (some of whom are also radical Islamic terrorists). The battle for Mosul, Iraq’s third-largest city, is almost concluded, but at enormous cost to Mosul’s civilians and the Iraqi army. Second, and more importantly, there is no agreement as to what will follow ISIS, particularly in eastern Syria. Here a new Great Game for post-ISIS control is being played out with increasing violence between the United States and Iran. Russia and a Kurdish-led militia are also key actors. If Iran and Russia win out (and at this point they are far more committed than the US), President Bashar al-Assad, whose repression and scorched earth paved the way for the ISIS takeover in the first place, may in the end be handed back the territories he lost, now burnt and depopulated. The Syrian people, who rose in democratic revolution six years ago, are not being consulted.

The battle to drive ISIS from Raqqa – its Syrian stronghold – is underway. The Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), supported by American advisors, are leading the fight. Civilians, as ever, are paying the price. UN investigators lament a “staggering loss of life” caused by US-led airstrikes on the city.

Though it’s a multi-ethnic force, the SDF is dominated by the armed wing of the Democratic Union Party, or PYD, whose parent organisation is the Kurdistan Workers Party, or PKK. The PKK is listed as a terrorist organisation by the United States (but of the leftist-nationalist rather than Islamist variety), and is currently at war with Turkey, America’s NATO ally. The United States has nevertheless made the SDF its preferred local partner, supplying weapons and providing air cover, much to the chagrin of Turkey’s President Erdogan.

Now add another layer of complexity. Russia also provides air cover to the SDF, not to fight ISIS, but when the mainly Kurdish force is seizing Arab-majority towns from the non-jihadist anti-Assad opposition. The SDF capture of Tel Rifaat and other opposition-held towns in 2016 helped Russia and the Assad regime to impose the final siege on Aleppo.

Eighty per cent of Assad’s ground troops encircling Aleppo last December were not Syrian, but Shia militiamen from Lebanon, Iraq and Afghanistan, all armed, funded and trained by Iran. That put the American-backed SDF and Iran in undeclared alliance.

The President’s Gardens

This review was published first at the Guardian.

This review was published first at the Guardian.

Since 1980, Iraq has suffered almost continuous war, as well as uprisings, repressions, sanctions, and war-related cancers. “The President’s Gardens” by Muhsin al-Ramli –published in Arabic in 2012 and now masterfully translated by Luke Leafgren – at last provides us with an epic account of this experience from an Iraqi, and deeply human, perspective.

“If every victim had a book, Iraq in its entirety would become a huge library, impossible ever to catalogue.” This book must belong to Ibrahim, nicknamed ‘the Fated’, the discovery of whose head (in a banana crate) opens and closes the novel in 2006, and whose life until that decapitation is narrated in the most detail. Yet Ibrahim’s friends since childhood, Tariq ‘the Befuddled’ and Abdullah ‘Kafka’, are essential to the story.

Tariq is a schoolteacher, a perfumed, snappy dresser, and a grinning, earthy imam. As such he is spared military service, and prospers in the village, making necessary accomodations to the ruling system.

Abdullah, the “prince of pessimists” who describes contemporary events as “ancient, lost, dead history”, is already alienated by his illegitimacy when he is called up in 1988 for the war against Iran, captured, and incarcerated as a POW for the next 19 years, with almost 100,000 others. In Iran he is paraded, tortured, starved, and lectured on Khomeinism. Prisoners are separated by religious affiliation, but those ‘penitents’ who adopt the Islamic Republic’s ideology are raised up to rule over the unconverted.

There is no sectarianism at all in the narration. The main characters, from north of Baghdad, are probably Sunnis, but the reader must bring knowledge from beyond the text to make this assumption. Their travels through the country’s beautiful landscapes and terrible warscapes convey a clear sense of Iraqi nationhood alongside a sustained disdain for exclusionary and propagandistic nationalism. “When I look at the flag of any country,” says Abdullah on his release, “I see nothing more than a scrap of cloth devoid of any colour or meaning.”

If Abdullah’s chief mode is principled nihilism, Ibrahim’s is gentle resignation. “Everything is fate and decree” is his catchphrase, and he names his daughter Qisma, ‘fate’. Made sterile by poison gas in the Iran war, lamed during the invasion of Kuwait, he finds a job in the paradisal gardens of the title, secret expanses within Baghdad studded by Saddam Hussain’s palaces, where the fountain water is mixed with perfume, camels graze between rose beds, and crocodiles swim in the pools. Naturally, horrors lurk beneath this surface.

The ‘Hakawati’ as Artist and Activist

I interviewed my friend Hassan Blasim, a brilliant writer and a wonderful human being, for the National.

I interviewed my friend Hassan Blasim, a brilliant writer and a wonderful human being, for the National.

Hassan Blasim is an Iraqi-born writer and film-maker, now a Finnish citizen. He is the author of the acclaimed story collections “The Madman of Freedom Square” and “The Iraqi Christ” (the latter won the Independent Foreign Fiction prize), and editor and contributor to the science fiction collection “Iraq +100”. His play “The Digital Hat Game” was recently performed in Tampere, Finland.

Because it’s so groundbreaking, his work is hard to categorise. It deals with the traumas of repression, war and migration, weaving perspectives and genres with intelligence and a brutal wit.

Why do you write?

To be frank, I would have killed myself without writing.

If you read novels and intellectual works since your childhood, your head is filled with the big questions. Why am I here? What’s the meaning of life? You apply this questioning to the mess of the world around you – why is America bombing Iraq? why are we suffering civil wars? – and you realise the enormous contradiction between your lived reality and the ideal world of knowledge. On the one hand, peace, freedom, and our common human destiny, and on the other, borders, capitalism and wars.

Writing for me began as a hobby, or a way of dreaming. And then when I witnessed the disasters that befell Iraq, it became a personal salvation. It wouldn’t be possible to accept this world without writing.

Maybe writing is a psychological treatment, or an escapism. It’s certainly a dream. But it’s also to confront the world, and to challenge all the books that have been written before. And it’s a process of discovery. It’s all of these things.

‘Criminals Kill While Idiots Talk’

The Pluto blog has published an extract from our book. Here it is:

The Pluto blog has published an extract from our book. Here it is:

‘Burning Country’, written by Robin Yassin-Kassab and Leila Al-Shami, explores the horrific and complicated reality of life in present-day Syria with unprecedented detail and sophistication, drawing on new first-hand testimonies from opposition fighters, exiles lost in an archipelago of refugee camps, and courageous human rights activists among many others. These stories are expertly interwoven with a trenchant analysis of the brutalisation of the conflict and the militarisation of the uprising, of the rise of the Islamists and sectarian warfare, and the role of governments in Syria and elsewhere in exacerbating those violent processes. In this extract taken from the book, Robin Yassin – Kassab and Leila Al-Shami dissect the 2014 seizure of Mosul and impact it had in Iraq and Syria and on international opinion.

In June 2014, ISIS led an offensive which took huge swathes of northern and western Iraq out of government hands. Most significantly, the city of Mosul, Iraq’s second largest, fell to ISIS on 10 June  after only four days of battle. General Mahdi al-Gharawi – a proven torturer who had run secret prisons but was nevertheless appointed by Prime Minister Maliki as governor of Nineveh province – fled, and his troops, who greatly outnumbered the ISIS attackers, deserted. This meant that the US-allied Iraqi army, on which the US had spent billions of dollars, was less able to take on ISIS than Syria’s ‘farmers and dentists’. Many Syrians saw a conspiracy in the Iraqi collapse, a play by Malki to win still more weapons from America, and by Iran to increase its regional importance as a counterbalance to Sunni jihadism. It’s more likely that the fall of Mosul was an inevitable result of the Iraqi state’s sectarian dysfunction. Shia soldiers felt themselves to be in foreign territory, and weren’t prepared to die in other people’s disputes. Many Sunni soldiers defected to ISIS.

after only four days of battle. General Mahdi al-Gharawi – a proven torturer who had run secret prisons but was nevertheless appointed by Prime Minister Maliki as governor of Nineveh province – fled, and his troops, who greatly outnumbered the ISIS attackers, deserted. This meant that the US-allied Iraqi army, on which the US had spent billions of dollars, was less able to take on ISIS than Syria’s ‘farmers and dentists’. Many Syrians saw a conspiracy in the Iraqi collapse, a play by Malki to win still more weapons from America, and by Iran to increase its regional importance as a counterbalance to Sunni jihadism. It’s more likely that the fall of Mosul was an inevitable result of the Iraqi state’s sectarian dysfunction. Shia soldiers felt themselves to be in foreign territory, and weren’t prepared to die in other people’s disputes. Many Sunni soldiers defected to ISIS.

ISIS’s control of the Iraq–Syria border, and especially of Mosul, was a game changer. The organisation collected the arms left behind by the Iraqi army, much of it high-quality weaponry inherited from the American occupation. Perhaps more importantly, it cleaned out Mosul’s banks. Then it returned to Syria in force, using the new weapons to beat back the starved FSA and the new money to buy loyalties.

The FSA and Islamic Front in Deir al-Zor, besieged by both Assad and ISIS for months, begged the United States for ammunition, warning the city was about to fall. Their plea was ignored, and the revolutionary forces (plus Jabhat al-Nusra) pulled out in July, leaving the province’s oil fields, and the Iraqi border area, in ISIS’s hands. ISIS reinforced itself in Raqqa and surged back into the Aleppo countryside and the central desert. Suddenly it dominated a third of Iraq and a third of Syria. In a tragic parody of the old Arab nationalist dream, it made good propaganda of erasing the Sykes–Picot border; in a tragic parody of Islamic history, it declared itself a Caliphate at the end of June.

The Prison

This article about Arab prison writing was published at the National.

This article about Arab prison writing was published at the National.

From ‘Prisoner Cell Block H’ to ‘Orange is the New Black’, prison dramas fill the Anglo-Saxon screen. In the Arab world, you’re more likely to see them on the news. In recent months, for example, detainees of the Syrian regime have staged an uprising in Hama prison and been assaulted in Suwayda prison.

No surprise then that contemporary Arab writing features prisons so prominently, sometimes as setting, more often as powerful metaphor.

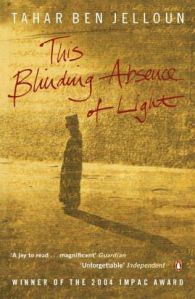

“About My Mother”, the latest novel by esteemed Moroccan writer Taher Ben Jelloun (who writes in French), is an affectionate but unromantic portrait of his parent trapped by incoherence. The old lady suffers dementia, mistaking times, places and people, but there is a freedom in her long monologues, the flow of memory and shifting scenes, torrents of speech which eventually infect the narration.

The novel is family memoir and social history as well as an experiment with form. Jelloun’s mother was married thrice, and widowed first at sixteen. At the first wedding, the attendants presenting the bride chorus: “See the hostage. See the hostage.”

Fettered by tradition and domestic labour, now by illness and age, she responds with superstition, fatalism and resignation. Her own confinement is echoed by memories of national oppression, first by the French, then by homegrown authorities. She learns to mistrust the police even before her son Taher’s student years are interrupted by eighteen months in army disciplinary camp, punishment for his low-level political activism. “That’s what a police state is,” the adult writes, “arbitrary punishment, cruelty and barbarity.”

Iraq’s Forgotten Uprising

This was published at al-Araby al-Jadeed/ the New Arab. The texts referred to are Ali Issa’s Against All Odds: Voices of Popular Struggle in Iraq, and Sam Charles Hamad’s essay ‘The Rise of Daesh in Syria’, found in Khiyana: Daesh, the Left, and the Unmaking of the Syrian Revolution.

This was published at al-Araby al-Jadeed/ the New Arab. The texts referred to are Ali Issa’s Against All Odds: Voices of Popular Struggle in Iraq, and Sam Charles Hamad’s essay ‘The Rise of Daesh in Syria’, found in Khiyana: Daesh, the Left, and the Unmaking of the Syrian Revolution.

A great deal has been written on the factors behind the rise of ISIS, or Daesh, in Iraq and Syria. Too much of the commentary focuses on abstracts – Islam in total, or Gulf-Wahhabi expansionism, or a vaguely stated American imperialism – according to whichever axe the author wishes to grind. And too much describes a simple split in these societies, and therefore a binary choice, between different forms of sectarian authoritarianism – in Iraq it’s either ISIS or the US and Iranian-backed government’s Shia militias; in Syria it’s either ISIS or the Russian and Iranian-backed Assad regime forces.

To take this representation seriously, we must force ourselves to ignore the very real third option – the non-sectarian struggle against the tyrannical authoritarianism of all states involved, whether Iraqi, Syrian or ‘Islamic’. Hundreds of democratic councils survive in Syria’s liberated areas, alongside a free media, women’s centres, and a host of civil society initiatives. In Iraq too, though it holds no land, there is a potential alternative, at least a gleam of light. The Iraqi state’s attempt to smother this gleam is an immediate and regularly overlooked cause of ISIS’s ascendance.

‘Iran the Protector’

Iran executes more people than any country except China. Many victims are Ahwazi Arabs or from other minorities. Many are political dissidents. And many, of course, are Shia Muslims.

This was published at al-Araby al-Jadeed/ the New Arab.

I recently gave a talk in a radical bookshop in Scotland. The talk was about my and Leila al-Shami’s “Burning Country: Syrians in Revolution and War”, a book which aims to amplify grassroots Syrian revolutionary voices and perspectives. My talk was of course critical of the Iranian and Russian interventions to rescue the Assad regime.

During the question and answer session afterwards, a young man declared: “You’ve spoken against Iran. You’ve made a good case. But the fact remains, Iran is the protector of Shia Muslims throughout the region.”

In reply I asked him to consider the Syrian town of al-Qusayr at two different moments: summer 2006 and summer 2013.

During the July 2006 war between Israel and Hizbullah, hundreds of thousands of Lebanese fled south Lebanon and south Beirut – the Hizbullah heartlands where Israeli strikes were fiercest – and sought refuge inside Syria. Syrians welcomed them into their homes, schools and mosques. Several thousand were sheltered in Qusayr, a Sunni agricultural town between Homs and the Lebanese border.

It made no difference that most of these refugees were Shia Muslims. They were just Muslims, and Arabs, and they were paying the price of a resistance war against Israeli occupation and assault. That’s how they were seen.

Their political leadership was also widely admired. The kind of people who would resist the pressure to pin up posters of Hafez or Bashaar al-Assad might still raise Hassan Nasrallah’s picture. During the 2006 war, very many Syrians of all backgrounds donated money to the refugees and to Hizbullah itself. The famous actress Mai Skaf was one such benefactor.

How quickly things changed. By 2012 Mai Skaf was embroiled in an online war with Hizbullah. “I collected 100,000 liras for our Lebanese brethren who fled the July 2006 war to Syria,” she posted on Facebook, “bought them TV sets and satellite dishes to follow what was happening in their countries, and bought their children shoes and pajamas. Now I am telling Hassan Nasrallah that I regret doing that and I want him to either withdraw his thugs from Syria or give me back my money.”